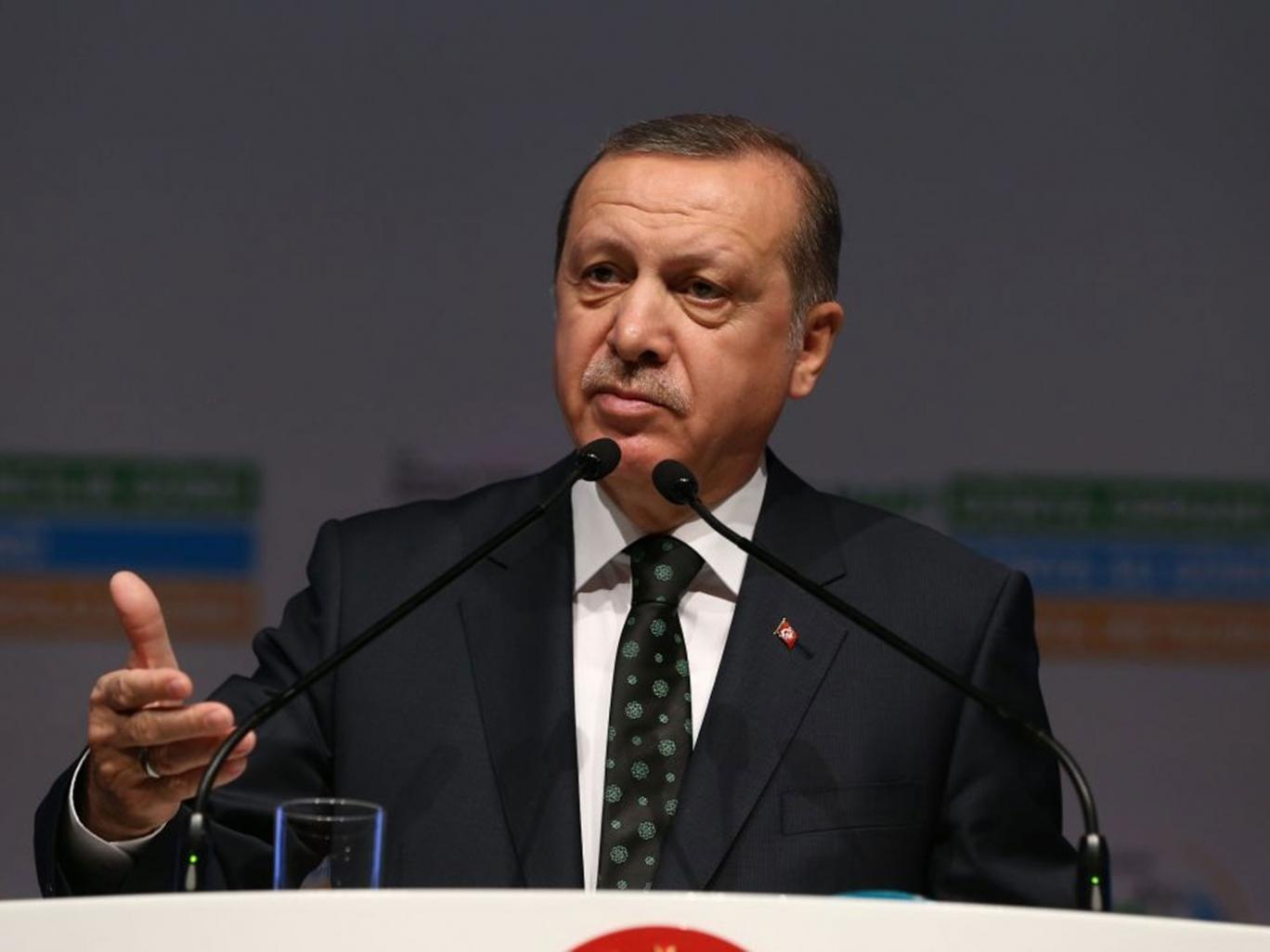

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan threw political prudence to the wind by opening Turkey’s and regional borders into questioning, after he disregarded the nation’s current geographical borders by saying that Turkey did not accept it with own consent.

Turkey’s Mosul conundrum took a more puzzling turn after Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi rejected U.S. pressure to allow a Turkish role in the campaign to retake the Iraq’s second largest city from Islamic State, ISIS.

After meetings with top Turkish officials, U.S. Defense Secretary Ash Carter said on Friday that Turkey and Iraq reached an “agreement in principle,” opening a way for Turkey’s involvement in the Mosul campaign. But on Saturday, the Iraqi prime minister staunchly refused any agreement, undermining the prospect for a Turkish role.

“I know that the Turks want to participate, we tell them thank you, this is something the Iraqis will handle, and the Iraqis will liberate Mosul and the rest of the territories,” Abadi told media after meeting with the Pentagon chief in Baghdad. Abadi underlined that it is Iraqi, Kurdish and other local forces that will handle the battle for Mosul.

The Iraqi reaction would likely jeopardize U.S. efforts to mediate a solution to the ensuing diplomatic row between Turkey and Iraq at a delicate moment as Kurdish peshmerga and Iraqi forces strive to make ways toward Mosul.

Erdogan’s evoking of Ottoman-era manifesto that envisioned borders of the country during dying days of the empire took a new turn on Saturday. He went a further step and expressed his outright disregard for current borders of Turkey, which he says, were not the one Turkey accepted voluntarily. “Our founding fathers were born outside these borders,” he said in the western province of Bursa at an event.

Most of the founding republican political elites, including Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, first president of the Republic of Turkey, were mostly born in the Balkans, areas that fell outside of Turkey’s borders when the republic was founded. But both Ataturk and his successors rejected an irredentist foreign policy to reclaim the lost territories, except Hatay from France in 1939, and mostly focused on nation-building at home in the nascent republic.

Realism was the core element of the Turkish republic, and the Turkish leadership, aware of the country’s dismal economic and military state, stayed away from adventurous policies in its external relations in early stages of the republican history. Second President Ismet Inonu did his outmost best to keep the country neutral during Second World War despite an earlier alignment with the UK and France in 1939 autumn.

“Republic is not the first state we [Turks] founded, it is the last one. We did not accept these borders full-heartedly [voluntarily],” Erdogan said.

Earlier in the week, he cited 1920-dated Ottoman National Pact or Oath, which designated the latest shape of borders that include today’s Mosul, Kirkuk and Aleppo. With 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, Turkey conceded to loss of many territories cited in National Pact (Misak-i Milli), and agreed to relinquish control of Mosul to the UK in 1926 in Ankara Agreement that settled last territorial dispute between Great Powers, or the UK, and the young republic.

Erdogan and other Turkish officials repeatedly brought the issue, at rambling length, in various cases. That sent rippling waves in neighboring capitals, with Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras deeming questioning of Lausanne Treaty as dangerous.

Greek Defense Minister Panos Kammenos warned Turkish leadership over pursuing “dangerous paths,” after Erdogan last month said by the Treaty of Lausanne Turkey gave away Greek islands that “you could shout across to.”

Erdogan’s bellicose rhetoric stoke flames over old settled issues regarding territorial settlement after the World War I that paved the way for the establishment of modern Turkey. While the Turkish president’s speeches infused and roused his core constituency and nationalists with passion over redesigning borders in Turkey’s favor, Erdogan’s irredentist tone has sparked a backlash from Greece, Iraq and other regional countries, which all found themselves wondering how serious Erdogan is in his remarks.

On Saturday, Prime Minister Binali Yildirim reiterated that Turkish warplanes would take part in the Mosul campaign, defying the Iraqi opposition to any Turkish role. Part of the reason for Turkey’s push is its fear for new refugee exodus from Mosul and a new sectarian bloodbath that could take place in the post-ISIS era.

Turkey has currently 500 troops at Bashiqa camp near Mosul. The Turkish forces are there to train local Sunni and Kurdish peshmerga forces. The Turkish military presence is the centerpiece of the conflict between Ankara and Baghdad amid Iraqi calls for a pullout of Turkish forces. With Carter’s visit to Baghdad ended in failure to convince the Iraqis to accord to Turkish role in Mosul campaign, the row seems to set to prolong further.