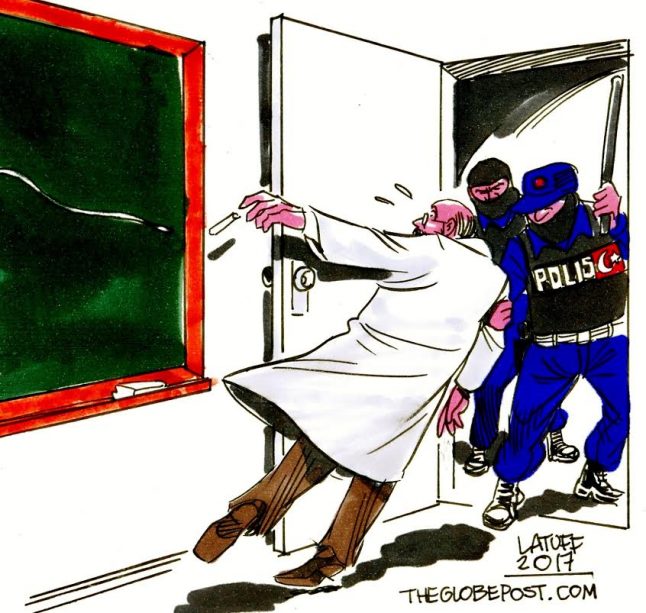

It was cold Istanbul night on Feb. 7, 2014, when I left the safe location where I was hiding for days and decided to surrender to the police at the Istanbul airport. As I turned myself in to the police, they escorted me to a plane that would take me out of Turkey. For good.

Two days later, then-Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan called me a “liar” during his parliamentary group speech and said it was up to the state press watchdog to issue press cards, not his government. Just 5 days before this incident, I was called into the police for questioning over a story that I made public about twin corruption investigations that targeted Mr. Erdogan and people in his inner circle.

I was the first journalist to be deported from Turkey. The authorities were quite inexperienced in dealing with the foreign press to the extent that the accusation leveled against me was a ludicrous one: Tweeting against senior state officials. Nothing like insult or spreading terrorist propaganda or revealing state secrets. Plain and simple: tweeting against senior state officials.

Since then, the Turkish government has escalated its crackdown on foreign journalists. At least 26 foreign journalists were either deported or denied entry since I was kicked out of the country 3 years ago. One foreign journalist still remains behind bars.

Deportation is not the only weapon the Turkish government is using to silence foreign journalists. On Monday, for example, German journalist for Die Welt, Deniz Yucel, was arrested after he reported about hacked emails of Berat Albayrak, the energy minister. In December, at least 6 Turkish journalists were detained on similar charges and 3 of them were arrested pending trial.

Journalists who were settled in and reporting from Turkey for years felt the biggest pain. Frederike Geerdink, who was one of few foreign journalists who dared to report about the Kurdish issue in the southeastern Turkey, was deported from Turkey in September 2015.

Her deportation came at a time when the Turkish government resumed military operations against the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), the Kurdish rebel group, and the war was brewing in the region. 3 journalists, two of them British, were also arrested for over a month. Jake Hanrahan and Philip Pendlebury from Vice News were later deported. Their fixer, Iraqi national Mohammad Rassoul, remained in jail for 131 days.

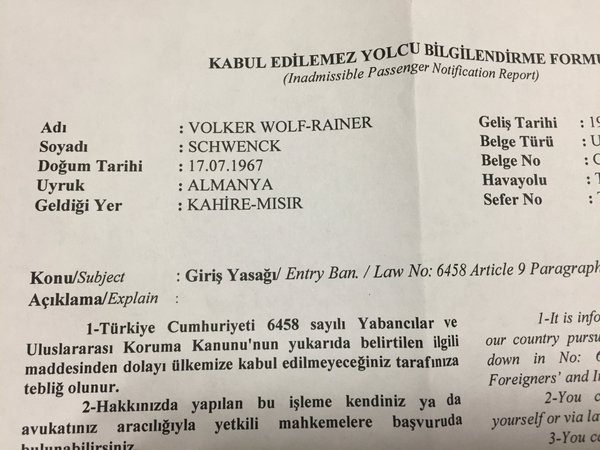

European journalists, particularly Germans, were the most targeted group of journalists. In one of the high-profile cases, Volker Schwenck, a reporter from Germany’s ARD, was detained at the Istanbul airport and deported. His German colleague, Der Spiegel’s Hasnain Kazim, had to leave Turkey after waiting for 3 months for his press card. Turkey’s press watchdog BYEGM usually issues press cards for foreign journalists in 3-5 business days. Andy Spyra, a German photojournalist, was denied entry into Turkey last March.

David Lepeska, American freelance journalist whose reporting appeared on the Guardian and Al Jazeera, was told in Istanbul airport to return home. Greek photojournalist, Giorgos Moutafis, was denied entry into Turkey as he was assigned by Bild to picture the plight of Syrian refugees.

British journalist Alex MacDonald was detained in Istanbul’s Sabiha Gokcen Airport last February as he was on his way to Gaziantep in southern Turkey. He told The Globe Post that he was interrogated by the police and then told he would be denied entry to the country.

“They took my phone, passport and other belongings and then detained me in a room overnight before putting me back on a plane the following morning. I presume it had something to do with my reporting from Diyarbakir the previous year. Since then I have attempted to purchase a visa and am consistently refused,” Mr. MacDonald said.

Aftenposten correspondent Silje Rønning Kampesæter, Norwegian, was also denied a press card last year because, according to the paper, her fiancé was ethnic Kurdish.

Turkey’s spat with Russia also took a toll on Russian journalists. Tural Kerimov, Sputnik’s bureau chief, was denied entry and his agency was shut down by Ankara.

French Olivier Bertrand, Spanish Beatriz Yubero and Natalia Sancha, Danish Claus Blok Thomsen, British Sam Tarling, Finnish Taina Niemela were either deported or denied entry on the border.

Since 2014, American journalists faced increasing pressure in doing their jobs. In the first anniversary of anti-government Gezi protests, CNN’s Ivan Watson was detained live on TV. The network later sent him to Honk Kong. As recently as in January, Rod Nordland, veteran NY Times reporter, was denied entry. Before him, WSJ’s Dion Nissenbaum was detained for 3 days in Istanbul and the newspaper decided to relocate him to Washington D.C.

The NY Times also started running anonymous bylines in its Turkey reporting, a practice that is usually seen in countries such as Syria, and relocated its Turkish reporter Ceylan Yeginsu to London.

Lindsey Snell, an American journalist, had to spend 2 months in a Turkish prison. She was detained after crossing into Turkey from Syria following a long captivity by al-Qaeda.

In the case of Rauf Mirkadirov, an Azerbaijani journalist for Zerkalo, the reporter was immediately arrested as soon as he arrived in Baku on espionage charges.

Dutch journalist Ebru Umar was briefly detained over tweets offensive to Mr. Erdogan, but denied by a court to leave the country after the release. She was later taken out of the country by the Dutch government.

Just days before the April referendum, Italian journalist Gabriele Del Grande was detained while interviewing Syrian refugees as part of his book project about the birth of the Islamic State. He remained behind bars for two weeks and eventually deported from Turkey under pressure by the Italian government.

********

This article was possible thanks to your donations. Please keep supporting us here.