In 1933, Adolf Hitler said his Reich would last for 1,000 years. In 1945, his country was in ruins.

In 1997, Turkish generals said their Feb. 28 regime would last for 1,000 years. Were they right?

Feb. 28 is the day when Turkey’s top national security council, dominated by the army, ordered the government to end Islamist activities, to transform the school system and to introduce harsh measures against the media, the judiciary, and the civil society. Then-Istanbul mayor Recep Tayyip Erdogan was soon to be arrested for reciting a poem, the media was to glorify the military and the judiciary would lock up anyone defying the military-dominated agenda.

The government of Prime Minister Necmettin Erbakan had to resign under pressure and his Refah party was banned. Religious schools were shut down, anti-military bureaucrats were sacked and the veiled women were refused to study at universities. The army, once again, reminded the Turkish people who the real guardian is.

Refined from the debris of the banned Islamist Refah Party, Mr. Erdogan soon built a conservative and progressive party that would become the nation’s most successful political entity — the AKP. It won election after election, lifted millions out of poverty, ended a decade-long political turmoil and financial meltdown, kick-started the EU accession negotiations and limited the role of the military in politics. But the country has become even more autocratic.

After late Prime Minister Bulent Ecevit’s DSP won the elections in 1999, Merve Kavakci, U.S.-educated Islamist lawmaker, was forced out of the Parliament amid thunderous protests of secular fellow deputies for wearing an Islamic headscarf. Sitting by her in solidarity was Nazli Ilicak, a fellow parliamentarian and a celebrated journalist, who is sitting in prison for 7 months. Mrs. Kacakci’s sister, Ravza, is a lawmaker from the government that locked up Mrs. Ilicak.

As Turkey marks the 20th anniversary of the 1997 military coup, feelings are mixed about the progress Turkey made in the past 2 decades. The ruling AKP is euphoric that it closed a chapter of the history in which the military decided which party was to stay and which party should go.

Dirayet Tasdemir, pro-Kurdish lawmaker, said on Tuesday that the “mentality that banned Merve Kavakci from speaking in the Parliament is the same with the mentality that stripped [Figen] Yuksekdag of MP status.” Mrs. Yuksekdag is the jailed co-chair of the HDP, the pro-Kurdish party.

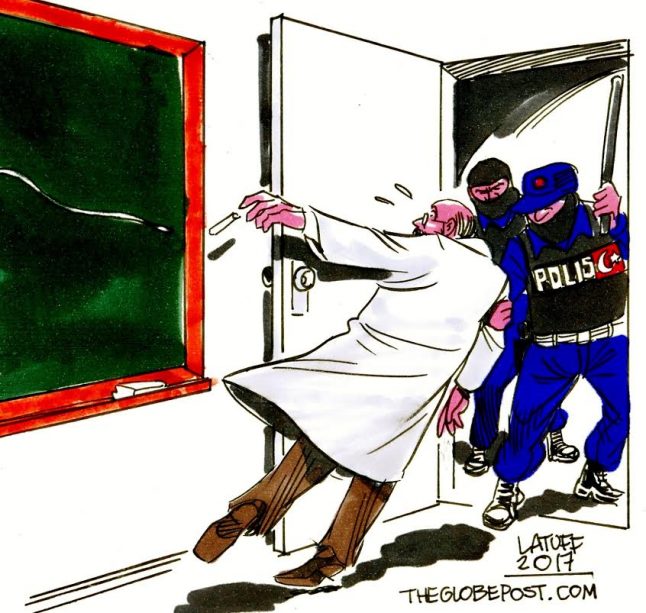

Different segments of the Turkish society are living so apart that while the governing party and its electorate cheer the end of Feb. 28 era, the opponents call it even a “worse period.” With 140,000 public employees fired in the past 7 months and 50,000 arrested since last summer, critics ring alarm bells about the toll this crackdown takes on the country’s media, civil society, and intelligentsia.

Mr. Erdogan is popular among his conservative base in part because he abolished the headscarf ban even in the military — the secular bastion of the republic. While veiled women could not study at universities 20 years ago, the situation today is not that different. At least 15 universities were shuttered, and over 5,000 academics were fired. Most of the 1,200 private secular schools that were seized by the government last year turned into religious schools or police stations.

While the media in 1997, led by Hurriyet, cheered the military-backed crackdown on opponents, it is poised for the same role for different causes today. Any journalist who dares to challenge the official narrative usually ends up in prison.

Perhaps the regime Turkish generals envisioned did not last for 1,000 years. But the method of crackdown they inherited seems to be alive and kicking.

********

This article was possible thanks to your donations. Please keep supporting us here.