A botched coup on July 15, 2016, sent the Turkish military, once a formidable actor with a wide-range political sway, into an institutional tailspin. One year later, the army is still in disarray, with officers are in the grip of perpetual fear of purge.

As the annual meeting of Supreme Military Council (YAS) in August took place on Wednesday, the officers’ corps feel the anguish of the uncertainty. A sense of dread and anxiety has dogged its members, with a new purge looming large given media reports about sprawling new lists. With the rank-and-file and senior leadership positions are up for grabs at the meeting that was expected to reshuffle the command structure, a shaky alliance between President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and secular far-leftist politician Dogu Perincek who has avowed acolytes and loyal disciples within the General Staff and the army ranks shows signs of fracturing.

True to their expectations, commanders of forces changed. Commanders of Navy, Air Force, and Ground Forces were replaced with new ones in an era-defining meeting on Wednesday. The meeting was regarded as the final seal of establishing civil supremacy over the once untamed military.

Since a debilitating purge decimated one-third of entire generals last summer, the Turkish military has increasingly become an arena of political turf wars and bare-knuckled battles. More than anything else, the Turkish media, during July, was awash with stories reflecting the political tug of war over the future of the army, the second largest within NATO.

Without a doubt, the last year’s abortive coup cruised Mr. Erdogan to a smashing victory over his political enemies, real and perceived. The army has been reduced to its former shadow, receded to an ineffective position with no longer sway on policy making and politics.

More than 160 generals are currently in jail. Given the burning need to fulfill the vacancies, there is an escalating all-out factional war to seize the control of the army leadership and senior command positions, a situation that came into full public view last week.

The first line of the battle took place over gendarmerie forces, regarded as Turkey’s military police in rural areas. Disappointed by the recent purge of their allies within the gendarmerie, the media arm of secular ultra-nationalists, OdaTV, launched a media blitz to rail against the shakeup.

The tussle has intensified since July 15, the first anniversary of the bloody coup attempt, an event that rattled Turkey, leaving 250 people dead and nearly 2,000 wounded. Though a year passed, the putsch still remains a contested story with too many narratives, mostly discrepant and conflicting with each other.

The insurrection abysmally crumbled after the military leadership, and pro-Russian, Eurasian factions forged an alliance of convenience with President Erdogan’s government against a bulk of supposedly Gulenist and Kemalist factions. Who was behind the coup, who pulled the strings, who planned and executed the ill-organized attempt are salient questions that still elude a satisfactory explanation. And the government’s blistering attacks against alternative sources of information and crackdown on critical media do not help either.

After a year, so many questions have gone unanswered. But what matters most is the fact that President Erdogan emerged as triumphant out of the failed putsch and made great strides toward his lifelong push: building an all-time powerful leadership thrived on centralization of power and leader worshipping by loyal masses.

The pushback of the ill-executed putsch, therefore, proved to be a pivotal moment both for his political career and the future of the battered military. President Erdogan was able to turn the “gift from God” to a windfall for himself and his government, initiating a purge campaign within the bureaucracy and the army with a great sweep unseen in Republican memory.

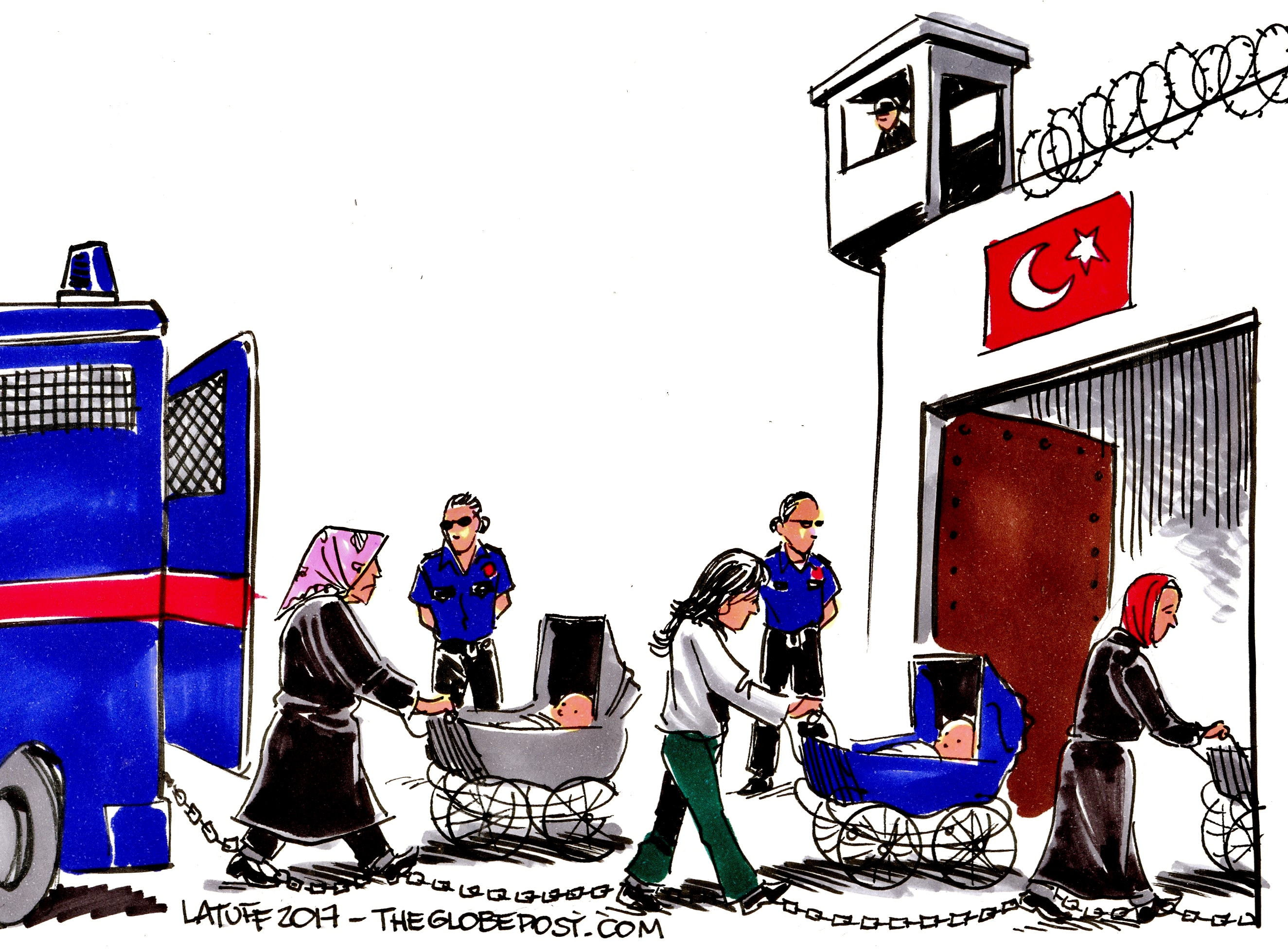

More than 150,000 public servants have been sacked in civil service. The purge also swept through the higher ranks of the army. Out of 348 generals and admirals, more than half of them were dismissed. To make matters worse, of all nearly 50,000 jailed people, 166 of them are generals and admirals while 6,810 are from lower ranks of the army.

The dismissals were so far-reaching and comprehensive that the Turkish Air Forces now faces an acute shortage of fighter jet pilots. It is a dreadful situation given multiple security threats in a conflict-ridden region.

Neither the president nor government nor the army leadership appear to have qualms over the morbid ramifications of the sweeping purge. But to seasoned observers and military experts, the state of affairs in Turkish military is no promising. It is even alarming, given the deepening sense of mistrust and suspicion among ranks, between officers, a factor that injected a poisonous element into a usually professional and apolitical military. Now the military is as politically divided as the rest of the nation.

For this and other reasons, this month’s Supreme Military Council (YAS) meeting marks another pivotal moment for Turkey’s once strongest institution. The timing could not have been more coincidental.

A major trial into the last year’s coup kicked off on Monday amid great public fanfare and media attention. Nearly 500 suspects, including former air force commander and other senior commanders, stand trial over charges of bombing Parliament, Presidential Palace, police special forces headquarters, attempting to dismantle constitutional order and toppling a civilian government.

Akinci Air Base was the place from where the majority of the violent action took place, to the astonishment of even some coup plotters who failed to make sense of the untrammeled and nonsensical violence. It torpedoed more than advancing the cause of putschists.

The start of the trial again dramatically raised the pressure on the military, with people flocking to the courthouse to unleash profanity-laced tirades against the defendants, vowing publicly displayed fealty to the president.

Media Battles Over The Future of Military

Last week, a brewing standoff between different factions was on full display when a pro-government newspaper run a headline that baffled secular ultra-nationalists. “Second Coup May Be Carried Out By Ultra-Nationalists,” the headline read, bringing emerging fissures into sharper public focus.

The target of the story was the faction represented by Dogu Perincek, a former fringe Communist firebrand who is widely believed to have significant sway over sectors of the military, be in senior command positions, in Navy, Ground Forces and Gendarmerie Forces.

His group closed ranks behind President Erdogan and played a key role to foil the attempted coup last year when a small faction of pro-NATO commanders abortively tried to remove the government.

The story of the intra-military power struggle between different groups harks back to late 2000s when infamous Ergenekon and Sledgehammer trials wrought havoc within the military, with hundreds of officers finding themselves jailed over what is now seen politically-motivated charges.

Whether they were totally sham trials, devoid of any substance, or not is a still a contested matter today, but its legacy for the military was not without ramifications. In 2013, hundreds of officers, including entire senior-level commanders of the navy, were sent to jail over a plot to remove President Erdogan’s government.

Some of the senior staff refrained from taking a robust stance against trials, therefore fueling a sense of deep resentment among their jailed colleagues. According to Omer Laciner, a former military member and Editor-in-chief of leftist Birikim magazine, this resentment found a clear expression in the form of a punishing revenge during July 15 coup attempt.

The long-brewing subtle struggle leaped into public view during last year’s bloody uprising. Shunned of support of the command structure, the attempt relapsed into chaotic violence and a definitive defeat by the government.

The secular and Kemalist segments of society placed the blame on Gulen movement and President Erdogan’s government for the controversial trials. After Mr. Erdogan and Gulen movement fell out in late 2013, the fate of trials and situation of convicted generals changed with the alteration of political currents.

President Erdogan whose own family members and cabinet members ensnarled in a sprawling corruption investigation struck a deal with the Ergenekon, Sledgehammer convicts against his former ally, Gulen movement.

With the stroke of a pen, the president and his government introduced sweeping changes in the judicial system, subjugating the judiciary into greater political control after the outbreak of the graft scandal. Those changes also affected the trials, with Constitutional Court, then Supreme Court, under political influence, overturned local court’s ruling about the trials.

Then the government embarked on its first phases of the purge against perceived and suspected members of Gulen movement in judiciary and police department. Nearly 2,000 experienced police chiefs were sacked, while judges, prosecutors and police chiefs who initiated and shaped the corruption investigation jailed.

After coup attempt, the purge took an epic scale, expanded to every sector of bureaucracy, and escalated with massive wealth grab and confiscation of properties.

When the pro-government ran that headline last week, many read it as a sign of new purge move by the government to the secular ultra-nationalist factions. OdaTv, Sozcu daily, and other secular media forums were furious in reaction, launched counter-campaign through a cascade of columns and press releases. They warned the government against the collapse of the alliance, which somehow managed to hold despite worlds-apart ideological differences.

Whether their fears would prove to be prescient is a matter to be known in upcoming weeks. After Wednesday meeting, President Erdogan approved new leadership reshuffle, which saw the promotion of dozens of colonels to generalships well before their time.

A Controversial Army Chief

At the center of swirling debates, one general stands out as a critical personality to be reckoned with. Despite all media buzz of a possible departure, Gen. Hulusi Akar, the army chief, appears to retain his position. More than anybody else, his name is ingrained in the pantheon of critical figures in the military history, but with all negative connotations. No other military figure is as controversial as Gen. Akar given his drama-filled tenure as military chief.

His displayed rapport with the president over the past year earned him acclaim among government supporters, but renewed skepticism and resentment within the purge-hit army. It is no wonder that secular media forums, close to Mr. Perincek and other opposition figures, ran a systematic campaign to discredit the army chief for his post-coup handling of the military affairs.

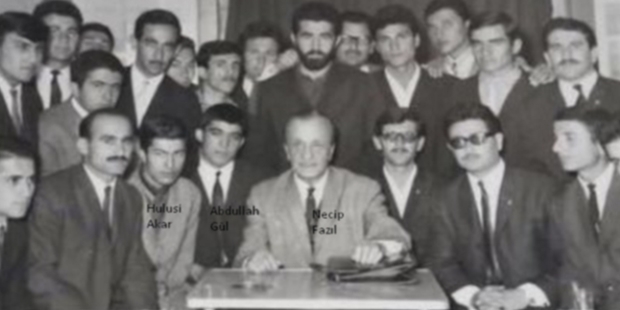

Months ago, several photos shared by OdaTV about Mr. Akar and his decades-long link to former President Abdullah Gul. The two, and other prominent Islamist figures, had photos together in London during late 1970s. Mr. Akar was a young lieutenant then while Mr. Gul was there for his studies. Mr. Akar’s obscure past, with possible Islamist upbringing, first time came to public view with the release of these photos showing him with a nationally famous Islamist-nationalist poet with a group of Islamist youth.

The group was the youth branch of a nationalist and religious formation, (Turkey Milli Kultur Vakfi), whose members later rose to prominent positions among right-wing and Islamist parties, including President Gul and incumbent President Erdogan.

Upon this startling revelation, many observers and commentators tried to explain Mr. Akar’s unshakable loyalty to Mr. Erdogan through the prism of these inter-related past relations formed within a certain ideological and intellectual milieu.

His leadership came at a time when the Turkish military underwent seismic changes, an unprecedented purge of its generals, public humiliation and torture of its respected senior commanders in videos released by the state-run Anadolu news agency. During his tenure, the Turkish military also plunged deep into northern Syria to fight the Islamic State and Kurdish militia.

What landed him at the heart of the political controversy was the opaqueness that surrounds his exact role during the putsch. Did he play a double role to fool and entrap the putschist officers by pretending to be as one of them? Or was he really taken hostage by putschists as the official narrative of the government put it? Why did it take too long (nine months) for him to answer questions of a Parliamentary Investigation Committee, which abruptly ended its mission before enlightening the riddling elements of the coup saga?

His role before and the during the coup attempt remains an enigma. As long as he serves President Erdogan’s agenda, his place seems to be secure, no matter what media reports say.