Before Vladimir Putin retained his grip on power for six more years in 2018 Russian presidential elections, the Kremlin had been frightening Russians with gays and communists into voting and arranging an isolation of Mr. Putin’s main opponent Alexei Navalny. Communist party candidate Pavel Grudinin and former reality TV show host Ksenia Sobchak were also among the candidates.

One month before the 2018 Russian presidential elections in March, the weather was too cold and snowy even by Russian standards. At the beginning of February, Moscow got monthly mean of snowfall in just two days. The city became an ice rink with pedestrians struggling to walk and cars buried under snowdrifts.

Mayor Sergey Sobyanin had promised to clean up the city in a week. The week had passed, but Moscow remained snowy and dangerous to walk. Then a Muscovite painted opposition leader Alexei Navalny’s surname on snowdrifts around her house.

In few hours, municipal workers removed the “Navalny snow.” Ever since media outlets reported on it, people all over the country have used this lifehack to rid of snowdrifts.

Removing the “Navalny snow” reflects the regime’s impatience with Mr. Navalny’s name as Russian authorities have been doing whatever it takes to eliminate his existence from the public face. Every time the opposition leader tries to organize events, the government deploys every type of tricks to either prohibit him or put pressure on his supporters.

Offices of Mr. Navalny, who is the most powerful opposition leader in the country, were searched, he and his core allies were jailed, and the state media was forbidden to mention his name. Even a group of half-naked escort girls were sent to his campaign office to embarrass him.

“There’s no official prohibition or directive. We are not in USSR anymore. But we are not fools, and we do know who is paying us,” a journalist who works for a state TV channel told The Globe Post on condition of anonymity.

“There’s no official prohibition or directive. We are not in USSR anymore. But we are not fools, and we do know who is paying us,” a journalist who works for a state TV channel told The Globe Post on condition of anonymity.

This trend was started by Mr. Putin who has never publicly mentioned Mr. Navalny’s name. His subordinates, however, have to say this name from time to time. Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev invented to call Mr. Navalny a “personazh” (character/person) and the nickname spread widely.

Alexei Navalny: Anti-Corruption Fighter

Forty-one years old lawyer and businessman Alexei Navalny is famous for his longstanding anti-corruption campaign. He established the non-profit Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK) whose main goal is to investigate and to expose corruption cases among high-ranking Russian officials.

As the FBK had been uncovering more and more secret palaces, businesses and yachts belonging to functionaries, Mr. Navalny became a pain in the neck for the Putin’s system that does not tolerate transparency.

The Kremlin tried in vain to isolate Mr. Navalny in prison by opening criminal cases against him. Courts handed down for the politician 8,5 years of a suspended prison sentence in total for two criminal cases. Mr. Navalny’s brother Oleg was sentenced to 3,5 years in prison for one of these cases.

Oleg Navalny is currently serving his time in prison although the European Court of Human Rights admitted both cases are unfair and illegal.

At the end of 2016, Mr. Navalny announced he was running for the presidency. Massive anti-Putin and anti-corruption rallies orchestrated by Navalny’s team in dozens of Russian cities throughout the year were an important part of the election campaign.

But all presidential candidates need to be registered by the Central Election Commission. The commission opened the registration in December, just several months before the polling day planned for March 18 — the day of the annexation of Crimea.

It took the commission less than a day to refuse to register Mr. Navalny as a candidate, citing his past criminal conviction as an excuse. The politician believes his conviction is politically motivated and the ban is unlawful because the Constitution says that only Russians who are under the age of 35 or were sent to prison cannot run for the presidency.

However, the election commission refers to a federal law approved during the Putin years that forbids citizens who have a suspended sentence to run for the presidency as well. Mr. Navalny described that law illegal as it contradicts with the supreme law — the Constitution. He promised to appeal the decision on all levels, though admitting that it wouldn’t change anything.

Following the ban, Mr. Navalny asked his allies to boycott the election. “The procedure that we’re invited to participate in is not an election,” he said. “Only Putin and his hand-picked candidates are taking part in it.” He also called for protests, and thousands of Russians went to demonstrations on January 28.

The Power of Television

Despite broad executive powers, the president of Russia still relies on TV networks to serve as his mouthpiece and to preserve the stability of his regime. 98 percent of Russian households own a TV set, and they watch TV between two to four hours on average a day.

Only cities with nearly one million inhabitants can offer various entertainment options, fixed salaries and consistent access to the high-speed Internet. People who live in smaller places have no option to spend their spare time but to watch the TV.

The government directly or indirectly owns all federal television channels. Under President Putin, the television has become a dominant propaganda tool. Trust in TV reporting among Russians, especially older ones, is still high.

This has compelled Mr. Navalny to launch his own TV. He started with a YouTube channel where he posts videos based on his anti-corruption investigations. Now he has his own newsroom, three YouTube channels with over two million subscribers altogether and nearly three million subscribers on other social media accounts.

So far, his most known movie about “secret corruption empire” of Prime Minister Medvedev received more than 26 million views while his most recent investigation about Medvedev’s deputy Sergei Prikhodko received over six million views.

According to Mr. Navalny, Mr. Prikhodko owns a real luxury property allegedly bought by bribes from Russian oligarch Oleg Deripaska.

Mr. Prikhodko met Mr. Deripaska on his yacht at least once. They went on a trip off the coast of Norway in summer 2016 accompanied by girls from an escort agency. One of them, Anastasiya Vashukevich, who goes by the name Nastya Rybka, posted photos and videos from the yacht on her Instagram account (later closed). In addition, she wrote a book called “A Diary of Seducing a Billionaire,” chronicling her infamous trip with the Russian oligarch and the official. She used fictional names to refer to the characters.

The FBK used Rybka’s book and Instagram account as the main sources of the investigation. Soon enough, Mr. Deripaska proved in a court that his private life had been recorded against his will. It allowed Russian communications watchdog Roskomnadzor to order YouTube, Instagram, and media outlets to remove the yacht video.

Moreover, the Roskomnadzor used the case to block access to the entire Navalny’s website as he refused to delete the investigation with “private life photos.” YouTube refused to delete the video too, but the watchdog did not block it.

Ms. Rybka’s so-called sex coach Alexander Kirillov, better known as Alex Lesley, said his residency in the Skolkovo Innovation Center was canceled. Eksmo publishing house also stopped printing Ms. Rybka’s book.

“People are afraid of everything,” Mr. Lesley said in his interview with the Navalny’s YouTube channel. “I am pretty sure Deripaska and Prikhodko have more important stuff to do than to pressure ordinary people like us. Nobody came to Eksmo and told them to drop the book. I think they simply got scared.”

Mr. Everlasting Leader

In early February, Vladimir Putin visited Akademgorodok, a scientific center of the third largest Russian city Novosibirsk in central Siberia.

Normally, Akademgorodok residents do not see asphalt from November to March due to too much snow. But a couple of days before the president arrived, the place — probably for the first time in its history — had been cleaned from snow up to the ground.

“Snowdrifts were removed. Everybody liked it,” Anastasiya Fedorova, the local, told The Globe Post.

“Policemen asked people not to watch Putin through their windows,” Ms. Fedorova recalled. “All attics and basements were sealed. All scientists got an extra holiday. And a person who picketed against Putin was arrested.”

“Policemen asked people not to watch Putin through their windows,” Ms. Fedorova recalled. “All attics and basements were sealed. All scientists got an extra holiday. And a person who picketed against Putin was arrested.”

Most polls indicate that Mr. Putin will be easily re-elected in March elections. Until a week before the elections, no one really knew what would happen in 2024. Will he step down or amend Russian laws to stay longer?

“I never changed the constitution, I did not do it to suit myself, and I have no such plans to do so today,” President Putin told NBC television. He rejected suggestions that he could not quit power because it would put him in danger, saying he heard “a lot of ravings on this subject”.

“Why do you think after me power in Russia will be necessarily taken over by people who are ready to destroy everything that I have done over the past years?” Mr. Putin said.

He said he had been thinking about his potential successor since 2000. “It never hurts to think, but at the end of the day, it will be the Russian people who will decide that,” he added.

How is a president elected in Russia? It is simple: all citizens older than 18, except prisoners or incapacitated, vote. A candidate who gets more than 50 percent of votes wins. If no one gets more than half of the votes, the two front-runners compete in a run-off.

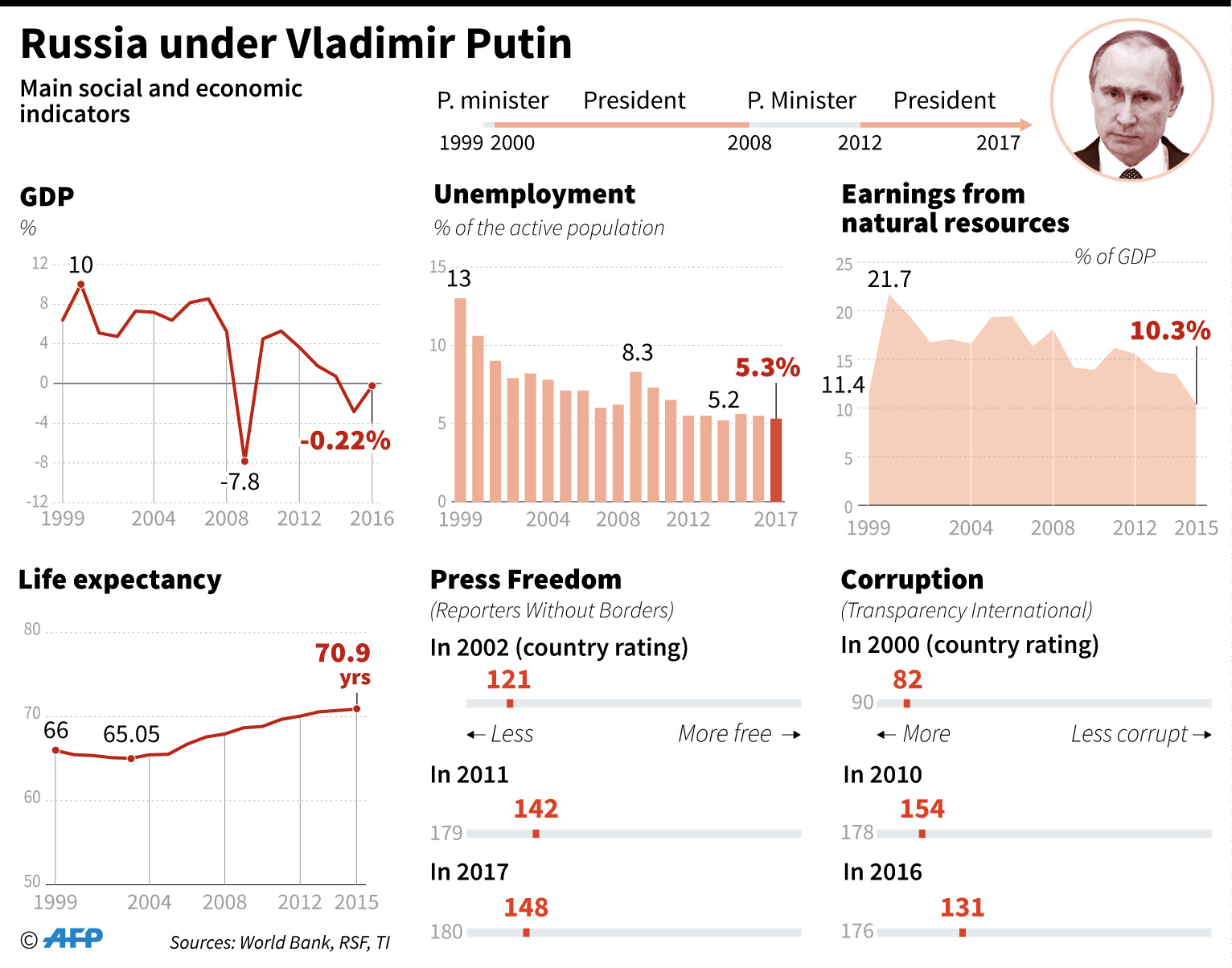

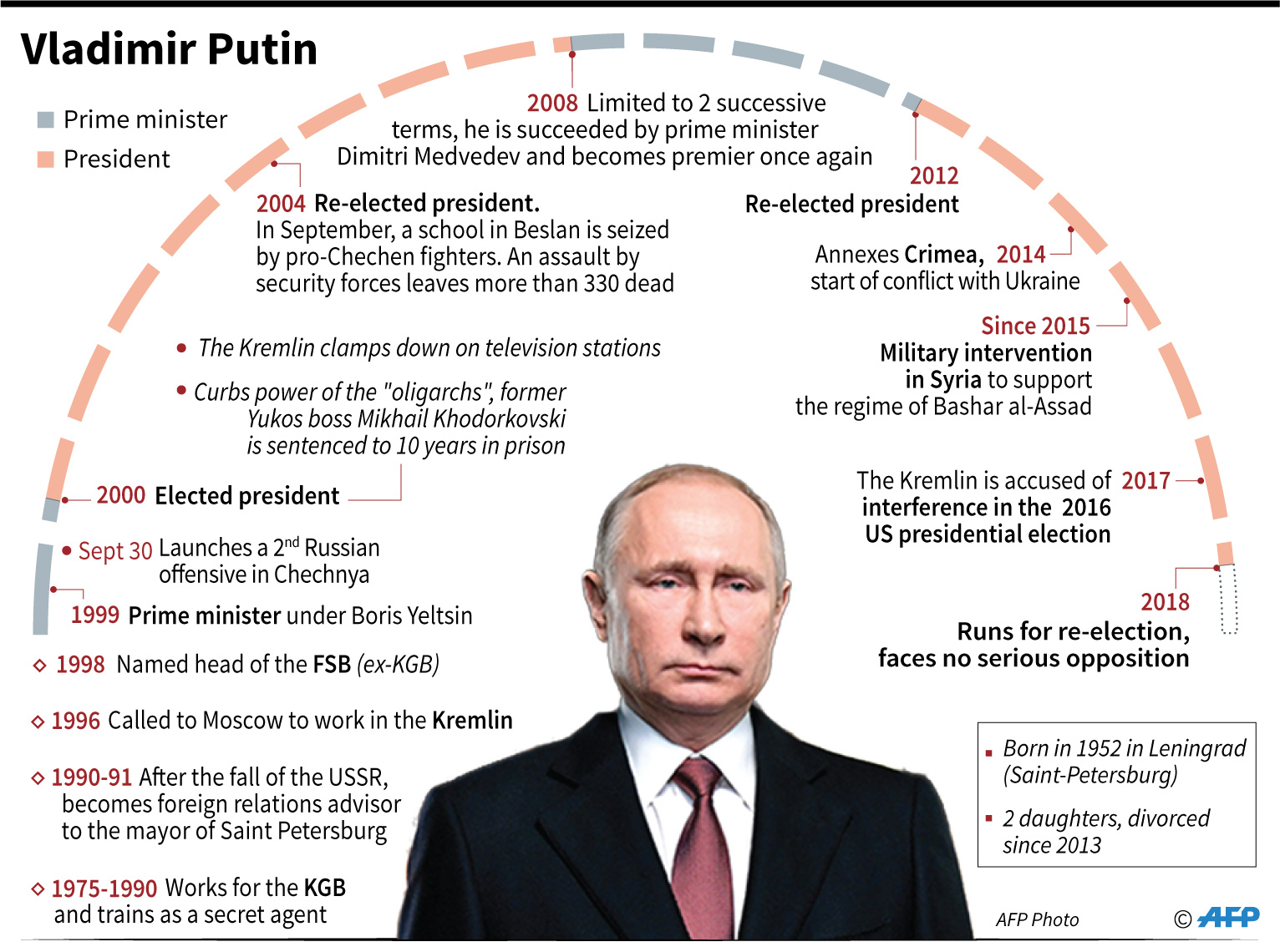

Before Vladimir Putin, a former Russia spy chief, won the presidential elections in 2000, he had been a less known official from the Boris Yeltsin team, the very first president of Russia. Mr. Putin spent 17 years of his 65 years of age in the office. If he wins again — and all experts approached by The Globe Post had no doubts that he would — Mr. Putin will be the president of Russia for another six years.

By the time of next election in 2024, he is going to be the longest-serving leader of Russia since Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin. In 2024, Mr. Putin will not be able to run for the presidency again. But only in case the laws will not change in his favor.

“During last 18 years, the power has completely lost its connection with the people. It is discredited, corrupted and dependent on Moscow bosses only,” political scientist Fyodor Krasheninnikov told The Globe Post.

Mr. Putin never provided his presidential program, but he used his annual speech to the Federal Assembly as an opportunity to articulate his main goals and values. The biggest part of 2018 speech was dedicated to Russia’s most modern and deadly weapons. “Nobody listened to us. Listen to us now,” he addressed the Western countries.

Mr. Putin concluded: “And for those who have been trying to inflate the arms race over the past 15 years, for those who have been trying to obtain unilateral advantages against Russia, introducing restrictions and sanctions that are illegal… I will say: all that you had tried to prevent has already taken place, it was not possible to restrain Russia. Now you need to realize the reality, to make sure that everything that I have said today was not a bluff — and this was not a bluff, believe me, to think carefully, to send those who live in the past and cannot look into the future for a deserved rest, to stop to rock the boat in which all of us are living and which is called the planet Earth.”

At first, he said he was going to have “something,” later he was supposed to present the platform in January, then — in February, he seemed to forget about it. There is no program section on his website either, although he made several program statements promising to raise social expenses.

Unlike Mr. Putin, Alexei Navalny produced a presidential program. Among other things, he campaigned to raise the minimum wage, which is now 10,000 rubles ($176) per month to 25,000 rubles ($440) and, of course, to fight the corruption.

The Russian state is designed in the shape of Western democracies, with the national assembly and the judiciary serving as a check on the government. But the Russian president wields enormous power. The Russian parliament Duma is nothing but a rubber-stamp assembly, and the government has a greater control over the judiciary.

The president can appoint all ministers including the prime minister, the head of Central Bank, some senators, judges, prosecutors, the military administration, and ambassadors. The president is the commander-in-chief. He or she can fire the government and dissolve the parliament, introduce a bill to the parliament and make his own decree with the significance of federal law.

Cost of Being a Dissident

In late January, someone trampled the word “thieves” on the snow near a historical citadel called Kremlin in Kazan, one of the biggest Russian cities. The police promised to find “snow artists” and make a criminal case against them.

While people in metropolitan cities can afford to express their opinions publicly, it is getting more and more difficult in small cities.

Ekaterina Lipinskaya, 28, lives in Krasnoslobodsk, a town in the Mordovia Republic, just 550 kilometers southeast to Moscow.

Krasnoslobodsk has 10,000 inhabitants, a museum where Ms. Lipinskaya works and a recreation center where her husband works. The town does not have a maternity hospital — it was transformed into a drug rehab since Krasnoslobodsk has more addicts than women willing to give birth.

Last year, Ms. Lipinskaya received a rebuke from the town’s mayor just because she cut her hair too short. Officials tried to make her change her hairstyle.

“We don’t have any open Navalny supporters because everybody is scared. It seems like the whole region has inborn Stockholm Syndrome! Everyone is afraid of expressing their opinions,” Ms. Lipinskaya told The Globe Post. Stockholm Syndrome is a condition in which a hostage develops a favorable opinion about his or her captors.

As a guide, she is making 17,000 rubles ($300) per month, a good salary for the province. Her husband is paid just 11,000 rubles ($200) per month as a light and sound director.

“All smart people of my generation left. All smart people of previous generations left, too. Only those who don’t care about anything and don’t want anything, stayed. These people are raising kids who soon will be the same.”

“Our museum is empty most of the days. We are trying to attract people, but it’s very hard,” she added.

Ms. Lipinskaya and her husband are going to move to Mordovia’s capital Saransk. This summer, Saransk will be one of the host city of 2018 FIFA World Cup. Local government needs money to organize huge events which is why they cut state employees’ salaries or even fired them just before the March elections.

“How are they going to win with people being angry about it? It’s easy: they will falsify the results,” Ms. Lipinskaya explained.

In the last parliamentary elections, her husband and his friend voted for PARNAS opposition party. When they checked results online, they realized that PARNAS got zero votes at their polling station — votes were erased or, more likely, given to the leading party United Russia, the ruling party.

“This time we are going to deface ballots. We hope they won’t be able to give our votes to ‘the right person’ if we do so,” Ms. Lipinskaya said.

She does not support Mr. Navalny’s boycott because she believes votes of boycotters will be given to Mr. Putin. Especially in towns where falsification is easier.

And small places are about to decide Russia’s future as nearly 60 percent of Russians live in cities and villages with a population under 250,000.

Putin’s Campaign for High Turnout

Many state employees spent January and February visiting Russian families and “inviting” them to presidential elections. “The invitation” included asking who is living in a particular apartment or a house; writing down their full names, professions, phone numbers and places of birth; asking whether they are going to vote and presenting election souvenirs as a gift.

When such a person came to Ms. Lipinskaya’s mother, she got angry with the local election committee which refused to provide voting at home for her 85 years old, sick mother, Ms. Lipinskaya’s grandmother. She told the inviting person that in this case, their entire family, including her daughter would not go to the polling station.

Next day, Ms. Lipinskaya got a call from her boss who was told that one of her subordinates is probably boycotting the election. The boss said Ms. Lipinskaya must vote otherwise she would be fired.

“This is how the system works,” Ms. Lipinskaya sighed. “I managed to convince them that it wasn’t me who told that I’m ignoring the election. They believed because I had a proof that I was out of the town the day the inviting person came to my mother’s house.”

Turnout is one of the main challenges facing Mr. Putin this time. Usually, only 60 percent of the electorate use their right to vote. During the Putin years, with people considering the outcome of elections as a foregone conclusion, ignoring elections has become a growing trend in the Russian society. If everybody knows who will win, what is the point of voting?

Mr. Putin seemed not to care about it before, but observers say this could be his last elections and he wants to crown it with a high turnout, a testament to his popularity and legitimacy.

“It is extremely important for Putin staff: this operation is got to be very successful. The turnout on the last legislative election in 2016 was lower than usual (48 percent), and they had to increase it through so-called ‘regions of controlled voting.’ It led to replacements inside Putin’s team, and some politicians’ careers skidded,” the president of the Foundation for Effective Politics, political strategist Gleb Pavlovsky explained to The Globe Post.

Earlier presidential elections in Russia needed more than 50 percent turnout, but the regulation was rolled back in 2006. What is the point for the Kremlin, after all, to try so hard to increase the turnout?

“I can’t think of any other explanation, but Putin’s will. He wants to win with a high turnout. He wants to show the world that he is special, that he is supported by most of the country’s population. That’s it,” Mr. Krasheninnikov said.

This and the desire to spoil Navalny’s boycott led to the biggest turnout campaign Russians have ever seen.

A lot of people complained on social media that their employers have made them promise to vote in writing, sometimes offering to cut their workday in exchange.

Since most polling stations are located in schools, some schools called for parent-teacher conferences exactly on Sunday, March 18, although such conferences are usually held on weekdays. In Dagestan, one of the most pro-Putin regions of Russia, pupils were asked to participate in “action”: they held banners that read “Thank you Putin” and “We vote for Putin.”

Many companies asked their clients to vote: the biggest Russian bank Sberbank sent its customers SMS notifications. Soccer games originally planned for March 18 were re-scheduled, and even Cosmopolitan invited its audience to the polling stations.

Vote or Lose

Emulating Mr. Navalny’s success with the youth, the Kremlin employed several media campaigns to lure young voters to ballot boxes. On YouTube appeared a viral video with a simple plot: a pretty girl meets a handsome young man at a nightclub. They seem to like each other. She takes his hand and leads him out of the party. The couple starts kissing.

The guy tries to undress the girl, but she stops him with a question “Are you older than 18?”

“Sure, I’m an adult,” he answers and resumes seducing.

“Have you voted today?” she continues.

“Nope, why?”

Instead of an answer, the girl pushes back the guy and says she cannot consider him as an adult in this case and goes away. The video ends with the election date.

There are more viral clips like this. In one of these videos, a pregnant woman gets on a cab and yells at the driver to “Go!” and “Faster!” and acting like she is already in labor. But it turns out she hurries to a polling station.

Another video is about a man who refuses to vote but has a nightmare in which he lives in Russia with “a wrong president.” The protagonist performed by well-known actor Sergey Burunov learns from an officer who looks a lot like a real presidential candidate, communist Pavel Grudinin, that the new president prolonged military enlistment age limits so he, 52 years old man, must serve in the army.

The man walks into his kitchen and sees a caricature gay man who is doing his nails. “What is THAT?!” the protagonist loses his temper. “I’m a gay on foster care,” the guest sounds offended. The protagonist’s wife tries to calm him: “The law says every family must foster parent a single gay. If he didn’t find a partner in a week, you would be his lover.”

Scared man tries to hide in the toilet, but an alarm warns he exceeded toilet visits limit.

The clip continues in that mood and when the poor protagonist wakes up, he is obsessed with a desire to vote. The message is clear: If you ignore the election, some wrong person — a communist who will limit everything or a liberal who will make all heterosexual men become gay — may win. “The right person” needs your support.

Although these videos aim to help Mr. Putin in his “high turnout” campaign, they are contradicting with his campaign motto “Strong President — Strong Russia.”

“If the president is so strong, why does he need ordinary people’s help?” some people ask.

“The turnout problem is a problem of reports to superiors. No matter how hard the Kremlin works on these ridiculous projects, the turnout will be higher than 60 percent, and Putin will get no less than 70 percent of the vote with any turnout,” Mr. Pavlovsky said. “You should be aware that there’s no choosing situation for the electorate. There’s a situation of confirmation that Putin is the everlasting leader of Russia. It’s just a ceremonial procedure and people who don’t have many interesting events in their lives will take part in it.”

Putin: The Best Man

On February 25, thousands of Russians marched in Moscow to remember the city’s late mayor and opposition leader Boris Nemtsov, who was murdered by an unidentified gunman on a bridge in the capital. A week after that, the Russian president also held a rally in Moscow, combined with a concert in his support. More than 130,000 people attended the event, including those who were sent against their will by their bosses, a common practice in Russia.

On February 25, thousands of Russians marched in Moscow to remember the city’s late mayor and opposition leader Boris Nemtsov, who was murdered by an unidentified gunman on a bridge in the capital. A week after that, the Russian president also held a rally in Moscow, combined with a concert in his support. More than 130,000 people attended the event, including those who were sent against their will by their bosses, a common practice in Russia.

“He is purposeful, he’s suffering for his nation, he believes in his nation and we believe in him,” a man who seemed to enjoy the event said.

“He is strong and masculine. He’s the best in the world,” a young woman explained her choice. “He is ‘our person’. He is one of the lads,” a young man added.

Russians still remember the early 1990s, when the country was gripped with economic turbulence and political chaos following the chaotic collapse of the Soviet Union. Money was scarce even to buy food, and whatever cash people had evaporated daily due to hyperinflation. The high unemployment, coupled with increasingly growing crime rate, made life unbearable for a nation that longed for its glorious past only a decade ago. Supporters laud him as a savior who restored pride and traditional values to a humiliated nation.

To foes, however, Mr. Putin has dragged his homeland further from democracy, has presided over a seizure of the state by a new elite of former secret police cronies and has stoked nationalism in a bid to restore Moscow’s lost empire.

Going near bankrupt, the Russian government had been doling out hitherto state-owned oil and gas reserves to wealthy oligarchs in exchange for desperately needed cash. When Mr. Putin consolidated the power in the 2000s, he annulled some of these so-called “Loans-for-Shares” and froze their assets. The most famous one was Yukos, owned by Mikheil Khodorkovsky, who was imprisoned for 10 years.

Mr. Putin was successful in lifting millions of people out of poverty, curbing inflation, rebuilding the military, creating some kind of political and economic stability, putting Chechen separatists under Moscow’s tight control and standing up to the West, a currency that sells well for Mr. Putin’s constituents.

TV networks undoubtedly played a significant role in polishing Mr. Putin’s image and tarnishing critics’ reputation. His supporters do not believe that a politician who had never ruled “anything big,” such as Mr. Navalny, can rule the entire nation.

“What does Russia need? To consistently finish building the statehood and to clear up a place on the world scene. And set the pace and the vector of the country’s development for the next 100 years ahead. As it was under Peter I or [Vladimir] Lenin. Only Putin is ready for this task,” a Russian who preferred not to mention his name told The Globe Post.

This person is sure that the next term will be the last for Mr. Putin and he needs this six years to finish his projects and “retire as a legend.” During the last 18 years, the country became stronger which resulted in massive anti-corruption campaigns started by Kremlin in 2016 all over Russia.

“Navalny and other public activists are very helpful: thanks to them, officials in the provinces are starting to work more efficient.”

As a result of the sanctions, Russia is developing its own manufacturing and reducing its dependence on imports, that person noted. And the service sector is more developed in Russia than in most Western countries with banks and government systems letting Russians get most of the necessary services online.

“Liberals call him a dictator who will never go away, but do they know for how long Angela Merkel is the Chancellor of Germany?”

Vladimir Putin has stamped his total authority in Russia, silencing opposition and reasserting Moscow’s lost might abroad. The 65-year-old former KGB officer has reimposed the Kremlin’s grip over society since taking power 18 years ago after a lawless but relatively free decade following the demise of the Soviet Union.

On the international stage, he has outlasted three U.S. presidents to become one of the globe’s undisputed strongmen, thrusting Moscow into a new rivalry with the West by snatching Crimea from Ukraine and launching a pivotal intervention in Syria.

Named the world’s most powerful person by Forbes for the past four years running, the judo black belt has built a macho man image helped by publicity stunts that included riding topless on horseback through the Siberian wilderness and darting an endangered tiger.

Bolstered by a slavish state media, he is projected to take around 70 percent of the vote by official pollsters, despite producing no programme and refusing to take part in televised debates.

The Kremlin picked March 18 to hold the election on purpose: on March 18, 2014, Crimea, a former part of Ukraine, was finally annexed by Russia. The annexation has since remained extremely popular among Russians. The nationalist fervor that swept across Russia following the annexation of Crimea catapulted Mr. Putin’s approval rating from 65 percent in January of 2014 to whopping 80 percent in just two months. Mr. Putin still enjoys similarly high popularity.

According to state pollster VTsIOM just one week before the elections, Vladimir Putin would return to the Kremlin with 69 percent of the vote.

The figure has dipped from highs of 77 percent shortly after Putin announced his candidacy in December, but there is little doubt he will win in a landslide even after a lackluster campaign.

Pavel Grudinin, the millionaire Communist Party candidate, is expected to come in second with around seven or eight percent of the vote, according to VTsIOM figures. Ultra-nationalist Vladimir Zhirinovsky is projected to garner around five percent, while former reality TV show host Ksenia Sobchak will likely take between one and two percent.

Ms. Russian Paris Hilton: Ksenia Sobchak

Ksenia Sobchak and Vladimir Putin have more in common than one might think. Both were born in Saint Petersburg, so-called north capital of Russia. Ms. Sobchak’s father, Anatoly Sobchak, was the first St. Petersburg’s mayor. He was also Mr. Putin’s boss when the future president worked for the city council in the 1990s.

When Mr. Putin was young, and Ms. Sobchak was even younger, he used to play with her when he was visiting Sobchaks. They even share alma mater: both studied at Saint Petersburg State University. Mr. Putin studied law, and Ms. Sobchak studied international affairs. She continued her education at Moscow State Institute of International Relations, also known as MGIMO University. In 2004, Ms. Sobchak graduated with master’s degree in political science. In the 2000s, Ms. Sobchak used to be a socialite, Russian Paris Hilton and “blonde in chocolate.” She started her career as the main presenter of reality TV show Dom 2, the longest-running Russian reality show that is largely dismissed as superficial.

Ksenia Sobchak, 36 years old former socialite and a journalist, is widely known thanks to Dom 2. Some 10 years ago, one could watch on TV how Ms. Sobchak clashed with another presenter Ksenia Borodina or discussed show participants’ relationships, an unlikely image for a presidential candidate.

After parliamentary and presidential elections of 2011-2012, Ksenia Sobchak was among the leaders of anti-government and anti-Putin protests in Moscow. It was very unexpected for a person with a lavish background, and she was not always treated with respect. For instance, people called her a “whore” and chanted “go away” during her speech at a rally in November 2011.

During a televised presidential debate in February, Ms. Sobchak had to throw water at ultra-nationalist and flamboyant candidate Vladimir Zhirinovsky after he repeatedly called her an “idiot.” He continued his insults by calling her a “f—ing whore” and a “dirt.” Pro-government media has been publishing her 20-year-old photos with revealing clothes in a bid to tarnish her reputation.

Despite all the challenges, Ms. Sobchak halted all her ongoing projects and became a “serious journalist.” She worked for the independent media, including the only Russian independent television channel TV Rain and edited L’Officiel magazine in Russia.

Last autumn, when Ms. Sobchak announced she was going to run for the presidency, it was little less surprising than her transformation into seriousness.

Surprise Candidate

On February 14, Ksenia Sobchak met her supporters in Kursk, a city close to Ukraine. She was given a bouquet “from citizens who fell in love with her,” she was greeted nicely as “the future president of Russia,” and she was surrounded by people in “against all” sweatshirts.

The “against all” motto has become a tagline for Ms. Sobchak’s presidential run. It started when she proclaimed at the start of her campaign that she did not like that the government’s exclusion of an “against all” or “None of the Above” option on the ballot for all federal elections.

Some parts of Ms. Sobchak’s electorate cross with Alexei Navalny’s voters. For this reason, she was blamed for disrupting Mr. Navalny’s campaign to boycott the polls and injecting legitimacy into an election that is expected to be rigged.

“If you want to vote ‘against all,’ vote for me. I am an ‘against all’ candidate,” Ms. Sobchak said.

It soon started to be clear that she wanted to be more than just a candidate soliciting protest votes. Ms. Sobchak’s presidential program is named “123 Difficult Steps” and consists of 123 reforms that she believes Russia needs. This is a comprehensive and quite a liberal program offering to make same-sex marriages legal, cut military expenses, and raise pensions.

In Kursk, Ms. Sobchak promised to her allies to discuss and sort out such local problems as high prices for urban planning, poor ecology, the lack of schools and destruction of architectural heritage. “Our people often think they can do whatever they want with their property even if it is a part of the heritage. I am against that.”

Ms. Sobchak was very passionate about her struggle against corruption, calling it as one of the chief woes in Russia. “Can you believe that I — the girl who hosts events, owns restaurants and some places for rent — turned to be five times richer than Putin according to our tax returns?!”

The audience laughed.

In Kursk, Ms. Sobchak also announced she made a complaint to the Supreme Court of Russia about Mr. Putin’s participation in the election itself. She believes he is violating the Constitution as there is a law prohibiting one person to be the Russian president more than twice consecutively.

But the Constitution has a loophole: it does not say one person cannot be the president more than twice if he or she has a break after the second term.

Although her supporters call her “the future president of Russia,” Ms. Sobchak says she has no chance of winning and she repeated it again in Kursk: “This ‘as if election’ can be won by one candidate only. His name is Vladimir Putin.”

“I am running for the presidency to tell people the truth about it,” she added.

“The casino always wins in the same way Putin always wins,” Ms. Sobchak told an audience in Washington D.C. in February. She visited Washington D.C. at the invitation of President Donald Trump to attend the National Prayer Breakfast.

In her speech in Washington D.C., she signaled that her political fortunes would start after this elections. She is planning to run for Duma and prove herself as a robust opposition politician and leader. She didn’t make it secret that she is preparing herself for the post-Putin era.

Mr. Putin had served as the Russian president two terms straight between 2000 and 2008. To bypass a constitutional restraint and engineer his return in 2012, Mr. Putin swapped jobs with his political ally Dmitry Medvedev, who was disregarded in the West as Putin’s pawn.

During Mr. Medvedev term between 2008 and 2012, the parliament amended the Constitution to raise the presidential term from four years to six.

In 2012, Mr. Putin secured the electoral victory again and Mr. Medvedev became the prime minister. The constitutional change allowed Mr. Putin to potentially rule the country for another 12 years.

In 2012, Mr. Putin secured the electoral victory again and Mr. Medvedev became the prime minister. The constitutional change allowed Mr. Putin to potentially rule the country for another 12 years.

Ms. Sobchak called Putin-Medvedev exchange “a unique acknowledgment of the two highest state officials that they made collusion aiming for permanent or long-term consolidation of the presidency for their group.” She claimed she was going to sue Mr. Putin for that.

The Central Election Commission replied almost immediately by stating that Mr. Putin has no prohibition to run for the presidency.

The next day, seven other people appealed to the Supreme Court about Mr. Putin’s participation in the election. It took the court one more day to reject the claims.

Mr. People’s Candidate: Pavel Grudinin

Except Mr. Putin and Ms. Sobchak, the Central Election Committee registered six other candidates, including two communists.

Pavel Grudinin, 57 years old general director of the Lenin State Farm (sovkhoz), represents Communist Party of the Russian Federation, or the CPRF. Several weeks after Mr. Grudinin started his campaign, thousands of bots posted comments on the social media in his support. All comments were the same: “I’ve never gone to elections before, but this time I will definitely go to vote for Grudinin. People’s candidate!”

Since then adding “people’s candidate!” to pretty much everything became the very thing in Russia and the Internet filled up with Grudinin memes

Mr. Grudinin has also become the most criticized candidate on state TV. It does not stop him from trying to convince people that the CPRF is a real opposition and Joseph Stalin was a great guy.

“[For the last one hundred years the best leader of Russia was] Stalin. He managed to increase the GDP. He was a person who transformed the absolutely illiterate country into a nation with the best education system in the world,” Mr. Grudinin said in his interview with Yury Dud.

Despite his admiration for Joseph Stalin, a notorious Soviet dictator, Mr. Grudinin has quite a few believers. A school in Ural region organized a competition between its pupils: children were assigned to paint “their candidate.” By default, children were supposed to draw Vladimir Putin, but one girl drew Pavel Grudinin. A teacher accused the girl of “illegal agitation” and took her picture away.

Despite his admiration for Joseph Stalin, a notorious Soviet dictator, Mr. Grudinin has quite a few believers. A school in Ural region organized a competition between its pupils: children were assigned to paint “their candidate.” By default, children were supposed to draw Vladimir Putin, but one girl drew Pavel Grudinin. A teacher accused the girl of “illegal agitation” and took her picture away.

“It is outspoken cynicism. They created obstacles killing any election intrigue. Of course, Grudinin isn’t an opponent, he has zero chances to win, but the Kremlin needs drama. They need people to believe that Grudinin is a strong antagonist, that the second round is possible etc. That is why he got such negative media coverage,” Mr. Krasheninnikov told The Globe Post.

Previously, the CPRF was represented by its leader Gennady Zyuganov, 73, who ran for the presidency four times, never won, but always came second.

Another election champion is Vladimir Zhirinovsky, 71 years old leader of the LDPR party (Liberal Democratic Party of Russia). 2018 election campaign is his sixth attempt to become a president. Although Mr. Zhirinovsky never got even 10 percent of the votes, he claims that he is going to win this time.

This is an election when the winner is predefined. Sergey Mironov, the leader of one of the four parliamentary parties, A Just Russia, has probably expressed what any other regime politician is afraid to say.

“With a sober look at things and respect to our voters, in an honest and open statement: we are not going to play in a performance with a pre-known finale. We are not going to participate in the run of fake candidates who are fighting for the second place with five percent of the vote. Let’s honestly tell our voters that we, like them, believe that there is no alternative but [Vladimir] Putin. We consider him the best candidate,” Mr. Mironov said after the party members have decided to not nominate anyone from A Just Russia to run for the presidency.

The Same Old Foreign Policy

Political strategist Gleb Pavlovsky is sure that “show election” cannot change anything. Foreign policy will remain the same and Russia will continue its military campaigns — although Mr. Putin once again said in December that the Syria operation ended. In February, however, he sent there 12 more fighter jets.

“Elections in this form don’t bind the president to anything, so can hardly influence his behavior. Reforms are always possible but with no connection to the election,” Mr. Pavlovsky told The Globe Post.

Political scientist Fyodor Krasheninnikov could not agree with him: “To reset relationships between Russia and Western countries another leader, another Russian president is needed. Putin, as an old, touchy and resentful man, brings to politics too many emotions. He accumulated a lot of personal offenses and ideological claims to the Western world. As far as he’s in the office, I wouldn’t wait for reforms to the better.”

Mr. Krasheninnikov thinks that the only difficult economic situation can stop Russia’s ongoing military campaigns.

Former U.S. President Barack Obama, however, predicted that Russia’s military adventures in Syria and Ukraine would doom the already sagging Russian economy. He justified his limited confrontation against Russian military campaign in Syria with an expectation that the military operations are usually costly and will pull down the Russian economy. His calculations turned out to be false.

Despite Mr. Obama’s attempts to reset the relationship with Moscow, the ties plunged to one of its lowest levels since the end of the Cold War. U.S. sanctions on Russia for destabilizing Ukraine have hit the Russian economy hard.

Despite Mr. Obama’s attempts to reset the relationship with Moscow, the ties plunged to one of its lowest levels since the end of the Cold War. U.S. sanctions on Russia for destabilizing Ukraine have hit the Russian economy hard.

“This election can’t influence the economy because there’s no election, just decorations, and the results are predefined. All processes in the Kremlin is not any way demonstrate they are contemplating an opportunity of changing the regime,” the director of Economic Policy Program at the Carnegie Moscow Center Andrey Movchan told The Globe Post.

Bolotnaya 2.0?

Legislative and presidential elections in 2012 ended up with large-scale protests in Moscow, popularly known as Bolotnaya rallies. Despite freezing cold, tens of thousands of people thronged to streets to demand Mr. Putin resign over fraudulent elections. The protests were the largest challenge to the 12-year-rule of the president. Mr. Putin could never forgive public support of Washington to protesters, particularly singling out then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and accusing her of inciting unrest in Russia.

For some observers, this enmity against Mrs. Clinton motivated Kremlin to meddle in 2016 U.S. presidential elections to tip the scales against the Democratic candidate and in favor of Donald Trump.

Mr. Movchan is not convinced that Bolotnaya demonstration could take place again. “There will certainly be some protests after elections,” he said. “But I don’t think 2012 events can repeat.”

“That rallies were in many ways caused by the outcome of the legislative elections and its extensive falsifications. People understood that if the elections were fair, the parliament would be completely different. The protest potential was much higher. And now Putin wins without any falsification. Well, something like 10,000 can fill up the streets — it’s nothing for the country with 145 million population.”

Alexei Navalny is the only person in Russia who can arrange notable protests. “But they won’t allow him — judging by obvious preparations for his new arrest, Navalny is likely to spend days of elections in jail. The Kremlin wants to remove this factor of uncertainty,” Mr. Pavlovsky added.

On January 28, Mr. Navalny was arrested for organizing an unsanctioned demonstration. The court could jail him for a month but preferred to let him go and prolong the case day in, day out. This scheme had already been tested on the chairman of the Navalny campaign Leonid Volkov: last autumn he was arrested during one of the rallies, released and jailed weeks later so he would spend in a cell the most important part of the campaign — the registration.

Furthermore, on February 22, Mr. Volkov was sentenced to a month in prison again, and again with a postponed execution. The same scenario is being written for Mr. Navalny as well, as he was charged with organizing the rally without a municipal permission.

“2012 rallies took place in Moscow only. So, I consider ‘enormous protests mythology’ flawed. Russia is a big country and until the provinces support the protest movement it all will be for nothing,” Mr. Krasheninnikov said. “2017 has shown us that there’s a chance.”

UPDATE: Putin won a landslide victory in Russia’s presidential election, receiving 76.67 percent of the vote, the central election commission said.

Putin, who has ruled Russia for almost two decades, recorded his best ever performance in Sunday’s polls, electoral officials said with 99.8 percent of ballots counted.