In the aftermath of the earthquake that struck central Mexico last September, social media websites were flooded with disinformation, hampering rescue efforts and the delivery of aid.

In the chaos of the disinformation, citizens, volunteers, and non-profits formed a group to verify the information that was coming in through social media. One of the founders stated that the original purpose of the group was to “manage data and fact check information” so they “could make citizen help more efficient during a time of chaos.”

This grassroots organization, Verificado 19s, became the most reliable source of information about the destruction of the earthquake in Mexico City. The organization became so reliable that when the Israeli army was helping with rescue efforts, they came to Verificado 19s for information on where to go because the government did not know.

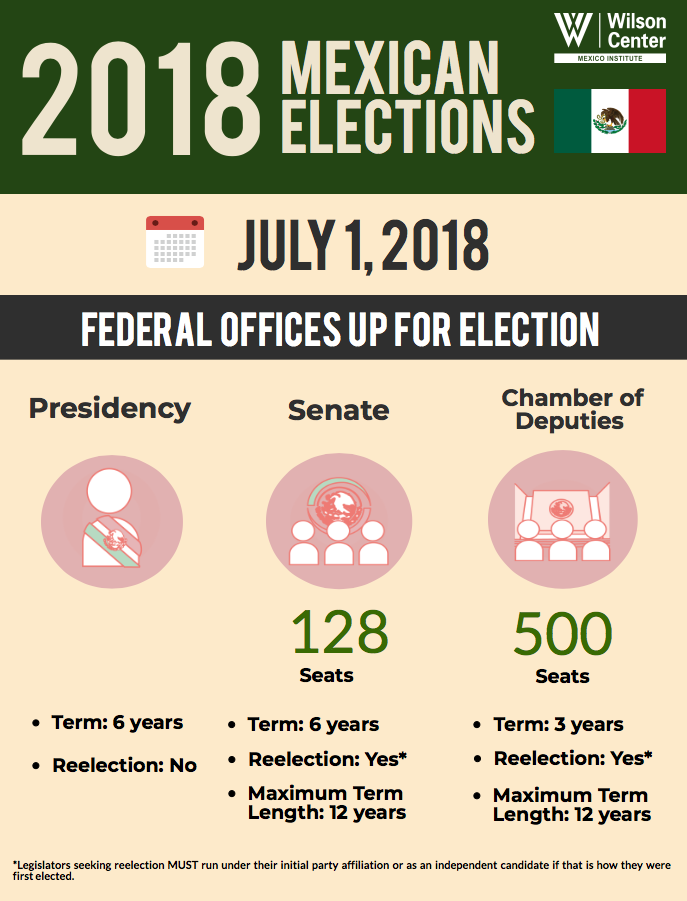

With the run-up to the 2018 general elections, which will be held on July 1, disinformation in the form of fake news is emerging on social media in Mexico. Seeing how effective Verificado 19s was at the time of disinformation, and by looking at how much of an effect fake news had in the 2016 election in the United States, a new organization, Verificado 2018, formed in Mexico to help combat the rise of fake news and preventing it from affecting the outcome of the vote.

The initiative launched in March of this year, just a couple weeks before the campaign season kicked off. It is led by Al Jazeera’s AJ+Espanol and the digital Mexican outlet Animal Politico, and includes more than 60 organizations ranging from news outlets to civil society groups, such as universities and non-profit organizations.

The organization was formed with the expressed goal to “disassemble false information” that could affect people’s votes. It does so by picking apart a fake news post and explaining, often in detail, the origin of the fake news or how something that may have actually happened was misrepresented.

In addition to fact-checking news that is spreading online, the organization will also fact-check the statements of the candidates themselves in an effort to help readers determine what is true and what is false. Readers can also submit news that is deemed questionable using #QuieroQueVerifiquen (I want you to verify), so the Verificado 2018 team can verify whether the information in question is true or fake.

The organization has also teamed up with the social media websites where the fake news is being propagated. Included as partners are Facebook, Twitter, and Google, where all of the companies have a role assisting Verificado 2018’s efforts to combat fake news.

According to the Verificado 2018 website, Facebook will notify the organization about the stories being shared the most among Mexicans, Google will provide information about what Mexicans are searching for and when the stories appear in their search engine they will have a “verified fact” (Hecho verificado) stamp, and Twitter will allow the organization to use lists and ”ads for good” so that verified stories will get preference in the feed.

Verificado 2018 has already debunked such fake news stories as the one about presidential candidate Ricardo Anaya saying he would help U.S. President Donald J. Trump build a border wall, and the one claiming the wife of presidential candidate Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador was the granddaughter of a Nazi general. Other debunked stories include a piece claiming the current first lady was one of the richest women in the world, another one on presidential candidate Jose Antonio Meade stating that Mexicans better get used an increase of gasoline prices that were imposed while he was finance minister, a proposal of a political party to reduce the number of representatives in Congress, and a Russian news report that President Vladimir Putin had decided to support presidential candidate Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador.

The Facebook pages that are the biggest sources of fake news are Nación Unida, Argumento Político, and Amor a México. Additionally, websites like El Mexicano Digital, Todo Informe, and Noticias Ocultas are also spreading fake news, according to Verificado 2018.

“We have detected internet sites that are born exclusively to spread false information; but the groups on facebook that are related to the candidates or against them are also a common source of false information,” Tania Montalvo, the editor of Animal Politico, told The Globe Post.

Yet it is still a mystery who is behind these types of websites and the creation of fake news. In Mexico, a country with a history of dirty elections, in which dirty tricks and vote buying is the norm, there appears to be a link between the creation and propagation of fake news articles and political parties attempting to sway the electorate.

Carlos Bravo Regidor, the director of the journalism program at the Center for Economic Research and Teaching, believes that this iteration of fake news that has appeared on social media in the run-up to the election is similar to past techniques of misinformation, and a technique that is being used by the campaigns themselves.

“I think, of course, the campaigns are a source of fake news against their adversaries. Of course, they would not do it openly, or evidently, but they have surrogates and, you know, the surrogates sell the whole package, not only producing fake news and publishing them, but also turning them viral through social networks, Facebook and Twitter, and so on,” Bravo Regidor told The Globe Post.

There have been reports of fake news in the past, with political parties contracting out to companies to create and spread the news. One company in particular, Victory Lab, a digital marketing company, has talked publicly about utilizing fake news and bots for their clients who are mostly politicians, making the business of fake news in Mexico a million peso industry.

A Freedom House report has noted that in Mexico “online manipulation and disinformation campaigns have been a recurring phenomenon since 2012.”

Despite the malicious nature of the creation of the fake news, Montalvo says there are people who share false information without knowing that it is fake and which could have a real effect on how people vote. In these cases, Verificado 2018 and their fact checking initiative can assist this demographic.

But, there is also another group that she notes is spreading fake news, “those with a clear objective of attacking an opposing candidate.” This demographic of people who spread fake news may be a lost cause for the organization.

“Fact checking assumes that the reading public is interested in the truth, that the reading public… has an interest in reason, in evidence” and from what Bravo Regidor has seen in response to Verificado 2018 stories is that some people are not interested in the truth and only want the news that is in line with their own beliefs.

“You need a rational public, you need a public that is interested in the truth. If you don’t have that the impact of fact checking projects is limited.”