Poverty in the United States is an issue that has existed as long as the nation has, and for that reason, is sometimes overlooked in the political realm.

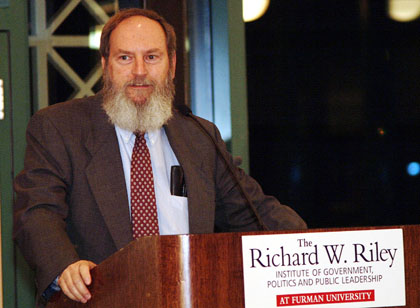

Pulitzer Prize-winning author David Shipler’s 2004 book,The Working Poor: Invisible in America, investigating U.S. poverty, looked to uncover the celebrations and struggles of those so often ignored as well as the systems that influence their circumstances. Nearly 15 years later, after a recession and two new presidents, he talked to The Globe Post about his observations over the decades. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: With many of your projects, you revisit the issues to see how they are progressing. Do you do that much with poverty?

Shipler: Well, I do it periodically. I write an occasional blog. What I’ve done with poverty is give a few talks about it to various groups at universities, so I’ve kept up with the subject that way. I have updated the book a few times, I think the last time was two years ago, so I think it’s about time to do it again. The updates involve statistics and data mostly, so I try to keep it as current as I can. These days they’re doing about one new printing a year.

Q: Given that you go back and look at some of these issues, what is your sense of the trajectory since the first printing of the book in 2004 and now in the United States?

Shipler: Well, a couple of things have happened I think. One is the dynamics of poverty and the interactions among the various problems that families face have embraced people that are considered middle class more than they did at the time that I was doing research for the book. You know, the economic collapse, the great recession in 2007 and 2008, as it has come to be called, plunged a lot of people who are in the middle class and lower-middle class into a zone of lifestyle and hardship that was just a little bit above the poverty line, but pretty close to facing the kind of problems that people in poverty face.

I think the kind of experience of difficulty has expanded downward, embracing more Americans than it had before. The statistics don’t show that, because people don’t fall below the specific poverty line, but if you’re working as a mechanic for an aircraft company, lose your job, and then get rehired as a subcontractor without the benefits for less pay, and then you don’t have the money to pay your mortgage and lose your home and so on and so on. You’re experiencing many of the dynamics that people in poverty experience, which is a sort of chain reaction of problems, one leading to the next. It’s very difficult to pull yourself out of it.

The other thing that would be important to emphasize would be the lack of change. Because even now when we see unemployment dropping very, very low, we haven’t seen, according to the official statistics, a significant increase in wages. So, people are working, and sometimes they’re working multiple jobs, but they aren’t being paid sufficiently to keep themselves afloat very well without some form of assistance. That’s a terribly difficult situation to be in. It’s not just a financial problem but a psychological problem. People might be doing everything the society considers morally right, working like crazy, but the take-home pay is so low that they really have trouble making ends meet. They don’t have any cushion, so if something goes wrong, they’re on the edge of real disaster.

Q: The poverty rate as a percentage of the population hasn’t really changed since the 1970s. What have you seen that would really work today to change that?

Shipler: First of all, direct income assistance is very effective. One program the U.S. government provides is the earned income tax credit. The EITC used to have very passionate bipartisan support because you get a payment when you file your income tax return. The payment can be more than what was withheld from your taxes. The payment is based on the number of children you have, the wages you earn, and so forth. It’s cash; it comes from the IRS, and it’s not really conditioned on anything except you do have to have earned income. You can’t get it without having a job.

That’s why Republicans liked it: it’s not available to people that aren’t working and it doesn’t create a new bureaucracy. The Democrats like it generally because it does provide a sort of safety net for people with low income, particularly with families. You don’t get much more money for having more than three kids, which is a problem with it, and it tapers off very quickly as your income rises. So, there are adjustments to be made, but it’s a good program. It’s helped people stay just above the poverty line, or get them out of poverty.

What’s really needed is a coordinated set of interacting government and private programs that address the multitude of interlocking problems that people face as a result of their lack of finances. A good foodbank, like Bread for The City in Washington, D.C., will have, in addition to people dispensing food, a medical clinic, maybe a lawyer to deal with housing problems, because a family that comes in with a food shortage will have these other problems. The school, police, hospitals or public housing authorities could create gateways through which they could access multiple services to address their problems.

This would require a financial investment beyond what the country has made, but in the long run, I think it would pay off. In the long run, like investments in healthcare, it would save the society a tremendous amount of money.

Q: I was struck by the way you wrote about healthcare in 2004, and how the same phrases are used today, and the same issues are being discussed, even after all these legislative changes. Why is there no progress here?

Shipler: Well, you have to ask the Republicans, don’t you?

First of all, there’s a general denial that government should spend money on healthcare. In fact, most dollars spent on healthcare in the U.S. are government dollars one way or the other. When you include the V.A., Medicare, Medicaid, CHIP and so forth, the notion that government shouldn’t get involved in healthcare is a fantasy. The population ought to be able to fill most of those needs through their taxes and government services. Medicare, for example, works very well. I’m on Medicare, and I benefit from that. That Medicare program could be made available to younger and younger ages. Not a government-run health service, but a government-paid health service could benefit the U.S.

Now there are always problems with a solution; any solution creates new problems. A single-payer system could create inflated costs, or a risk of rationing, people overusing the system to the extent that they’re denied access to certain tests, longer waiting periods. There could be all kinds of difficulties, but generally, access to healthcare is really essential. For a very wealthy, industrialized country such as the United States not to provide it is a huge shortcoming. It’s really a liberal versus conservative issue. So as long as Republicans are the party that they are, and the party that they’ve become, further to the right, I don’t think we’re going to see any real change in this regard.

Now that they might want to dismantle the parts of the Obamacare program that require insurance to provide for preexisting conditions is just criminal. There’s no other word for it. There are millions of people with preexisting conditions who, if this goes through, are going to face either huge premium increases or no insurance at all. That’s just unthinkable. It just makes you want to weep.

Because Obamacare was a compromise between the single-payer and swashbuckling insurance systems, and it did make some improvements: preexisting conditions, allowing children to stay on their programs until after college, subsidies for premiums of people in that middle ground that can’t afford the prices of the free market and not getting it through their employers. All of that was a patchwork approach to addressing some of the real problems that have existed for a long time.

It’s political and economic. It’s a matter of political will, because this country can afford it.

Q: Income inequality is quickly growing in the U.S. with the poverty rate hardly budging. Is there any reason for hope, that poverty in the U.S. will get better?

Shipler: Well, one always has to have hope, because if you don’t, you give up on trying to solve the problems. In the United States, because we have a myth about equal opportunity, not equal results, and it is a myth, it helps set a high standard for us that we need to achieve. So, we want to reduce the gap between the reality and the ideal. Americans are unique in the way we regard poverty, because in America, you’re supposed to work your way out of poverty, and work is an ethic. In the U.S., there’s an overtone of blame that is directed at the poor.

You see it in legislation, in the work requirements now being attached to Medicaid, maybe to the food stamp program. There’s an implication that people that need this help are lazy, and somehow, the establishment has to enforce our ethics, which means going to work to earn these benefits. There are lots of benefits that people get at higher income levels that don’t require work, so there’s a certain punitive overtone to the Republican policymakers.

As I have found in my book, responsibility for poverty is distributed widely between societal and individual failings. You can’t categorize a particular family or person neatly into a box and say that it’s all their fault or it’s all the society’s fault. It’s often an interaction between various issues along that spectrum.

What we need in this country is to get beyond the ideologies, beyond the dispute, which is hardly a debate, and understand poverty in a nuanced and sophisticated way. It’s not all the fault of the society, and it’s not all the fault of the individual; it’s a combination of both and the interaction between them. We have to address both.

We don’t understand some areas, of course. By we, I mean the society. But we have the skills in many areas to understand what needs to be done. We often don’t have the will to fix those problems though.

We’re in this together. We all have to work together to figure this out and not hate each other because of our own hardships.