Humanitarian organizations have only secured 35 percent of the funding they need to provide relief to crises around the world so far this year, according to the Norwegian Refugee Council report from July.

Non-government organizations join the NRC and the United Nations in their crisis of funding to support international interests. António Guterres, the U.N. secretary general, sent a letter to member states explaining the problems facing the organization last week.

“Our cash flow has never been this low so early in the calendar year, and the broader trend is also concerning: we are running out of cash sooner and staying in the red longer,” Guterres said in the letter.

Though funding is low for many of these organizations, that shortage is passed on to communities in crisis that usually benefit from humanitarian aid.

“These crises are not just forgotten,” the NRC said in another report. “We use the word ‘neglected’ to highlight that the lack of attention towards these crises is the result of an intentional inaction, based on indifference or lack of prioritisation.”

The top five nations that the report finds to be neglected are in Africa, including South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The DRC has never had more people displaced than it did in 2017, totalling 4.5 million according to the report. Lack of safety, healthcare, food, and shelter have altered the lives of many Congolese.

One in ten children in the Kasai province is suffering from severe acute malnutrition, a U.N. Children’s Fund report said. Violent conflicts interrupted many children’s education and vaccine schedules, which will lead to future instability in the region. Outbreaks of cholera and measles are already being reported, according to UNICEF.

Humanitarian organizations often focus on containing the crises before secondary consequences arise from the original problems, such as disease coming from violence in the DRC.

“The best long-term investment is creating national, regional and global stability via the early recovery of the affected communities,” Tuva Raanes Bogsnes, head of Media and Communications at NRC told The Globe Post. “Too often, crises are ignored until the financial and logistical needs become too onerous for the international community to fulfill.”

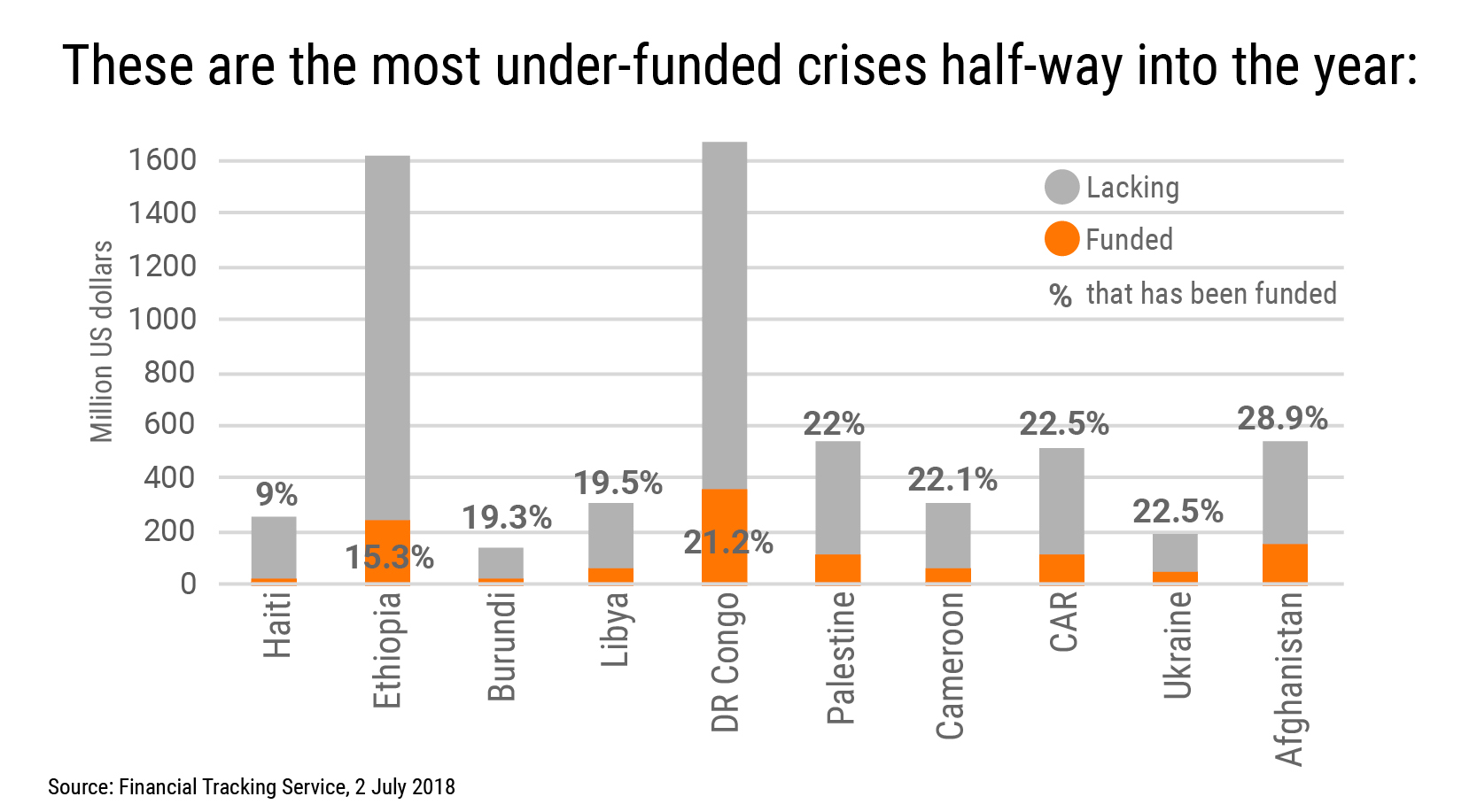

With funding below what is needed to address all humanitarian needs around the globe, some crises are supported more than others.

“The scale and acceleration of each displacement situation, combined with geopolitical interests and the ripple effect on the surrounding regions, often impact the funding commitments,” Bogsnes said.

The situation in Afghanistan is a good example of funding being used according to changing needs. NRC currently reaches more than 380,000 people in need of basic assistance. Some of these people flee to more rural areas, where a recent drought is expected to leave 2 million Afghans food insecure in the coming months.

“Without sufficient emergency funds, we would be forced make decisions about whom we can help and who will go without,” Bogsnes said.

Some situations can be even more dire. When an Ebola outbreak was declared in May, panic over the virus gripped many in the area. Many in the global community were also concerned about the disease spreading internationally. Some $57 million was released in ten days, according to Bogsnes.

“This same efficiency and financial commitments should be applied to the broader humanitarian crisis in DR Congo, which received a mere 21 percent of the needed funds,” Bogsnes said.

The U.N. came up over $11 billion short last year for humanitarian funding and Bogsnes predicts it will likely fall short again in 2018; $15.9 billion more will be needed by the end of the year. However, more funding has been secured for individual crises which Bogsnes counts as a success.

One of these successes took place in Somalia, where the E.U. and five international NGOs spent three years on the Building Resilient Communities in Somalia project. The support, which began in November 2013, “bore a remarkable level of impact in building the resilience of over 30,000 households. Timely aid deployment, focused on long-term development, helped resuscitate and rehabilitate communities,” according to Bogsnes.

Still, the larger financial problems are persistent.

The U.N. estimates $25.4 billion will be needed internationally for humanitarian aid in 2018, while the international military expenditure is over $1.7 trillion, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. The gap between needed humanitarian aid and actual funding received has grown since 2012.

Without enough funding for specific crises, “the outcome is obvious,” Bogsnes said, “exacerbating crises and the destabilization of entire regions.”