On August 17 a year ago, a terror attack in Barcelona killed 14 persons and injured more than 130. The terrorist drove a van at high speed through a pedestrian street, La Rambla, which is popular with tourists. The driver, later identified as Moroccan-born Younes Abouyaacoub, fled the scene and was shot and killed by Spanish police several days later.

Jump ahead a year to the recent terror attack in London: another car driven with intent to kill plowed into bicyclists and pedestrians outside the Palace of Westminster, home of the British Parliament. This time there were injuries but, fortunately, no fatalities.

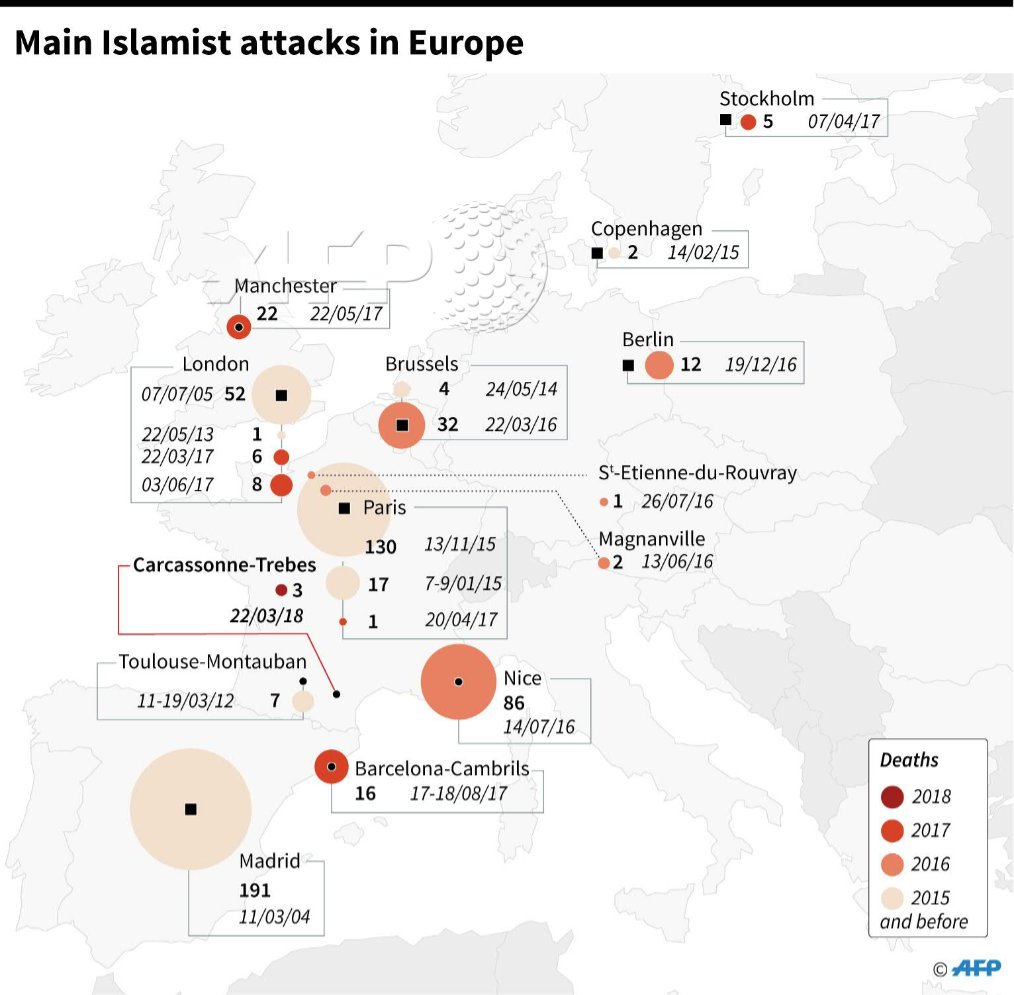

These incidents and others like them show how difficult it is to deal with terrorism generally and Islamic State in particular. Unlike the 2015 attacks in Paris, which were directly organized by Islamic State, the Barcelona and London attacks were apparently merely inspired by Islamic State, which continues to produce online exhortations to kill those they designate as enemies.

How can counterterrorism agencies stop someone who is motivated to act by this messaging but has no detectable ties to any terrorist organization and needs no bomb or other weapons, just a car or truck?

The answer is, they can’t. Unless the perpetrator is sloppy in his or her preparations for an attack and law enforcement or intelligence agency is alerted, there is virtually no way to prevent an individual or a small group (as was the case in Barcelona) from carrying out this kind of violence.

If the inspiration for terrorism is coming from social media and other internet venues, that must be a principal battleground where counterterrorism efforts operate, maintaining a pervasive, persistent counter-messaging campaign, using the same online tools that Islamic State and other terror groups have relied on. In the years since the 2001 attacks on the United States, the U.S. government has gradually become more sophisticated in this work. Extremist pronouncements cannot be allowed to exist unchallenged, and misleading promises of a religious or political haven must be deflated. But as counterterrorism officials have learned, even with the help of social media companies, it is impossible to halt or counter every terror-oriented message. That is why using online venues to counter extremist content must be innovative and constant.

Such constructive efforts are not helped by politicians’ occasional pronouncements that “Islamic State has been crushed” and such. Those statements are not just nonsense; they are dangerous nonsense. They distract policymakers and the public from the realities they must confront in terms of maintaining pressure on terrorist organizations. Turning off the recruiting faucet that is essential to these organizations’ futures and preventing terrorists from finding new sanctuaries are tasks that require commitment and resources.

This includes “boots on the ground,” another politically challenging commitment. Kinetic responses to terrorism remain essential, and they can be most effective if delivered in a timely fashion. Just as al-Qaeda used Afghanistan as a base of operations during the 1990s, today al-Qaeda, Islamic State, and groups such as Boko Haram are becoming more firmly entrenched in Africa.

Although terrorism in Africa has not received as much attention in most Western news media as was accorded to terror organizations in the Middle East, underestimating the size and viciousness of Africa-based groups would be just as dangerous as were the misjudgments about al-Qaeda 20 years ago. Despite this, the U.S. is reportedly considering a significant withdrawal from Africa of its counterterrorism forces. That would be a potentially tragic error.

On this anniversary of the Barcelona murders, and with the reminder offered by the London attack, people around the world should recognize that terrorism is alive and well. Defeating it will require long-term resolve from governments and the public, and any slippage into nonchalance will certainly lead to dire consequences.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of The Globe Post.