Creating external crises to deviate from internal problems is a well-known recipe in politics. Unpopular dictators often resort to this tactic to shape the discourse and concerns of the opposition, media, and population. In Venezuela, President Nicolas Maduro has adopted this tactic since day one. The regime’s latest attempt to induce a crisis was fabricating the notion that the opposition, in collaboration with the U.S., sought to end Maduro’s life with a drone attack. Nobody has taken this story seriously. Thus, this piece will not waste time discussing the drone affair but will instead focus on five issues that really matter.

Nobody Chose This

When thinking about the Venezuelan crisis, one might erroneously believe that people chose this type of regime. That is a mistake. When Venezuelans hit the polls in 1998, they elected someone who they thought would refresh Venezuelan democracy, make the economy grow, eradicate poverty, and decentralize power.

But that is not what happened. As oil prices went up, elected President Hugo Chavez began to erode horizontal control institutions, thus burying what was once a more or less stable democratic system. This allowed the creation of massive clientelist networks, the expropriation of the majority of the most important businesses and industries, co-optation of the judicial and legislative branch, and the persecution through several means of all those who did not support his project. Most importantly, Chavez implemented elections almost on an annual basis to give “legitimacy” to an authoritarian government.

Working under an electoral facade, he made Venezuelans and the world believe he was expanding democracy, while in real life, he was cementing a stable autocracy.

Refugee Crisis

For the first time in its history, Venezuelans are forced to leave their country due to political and socio-economic reasons. Only a few decades ago, Venezuela became the destination for thousands of citizens from Africa, Europe, Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America who were seeking a new home.

Today, at least two million Venezuelans were forcefully displaced to Colombia, Brazil, Peru, Ecuador, Argentina, and Chile, just to name a few. The overall figure of the Venezuelan diaspora easily surpasses the four million thresholds. It is the largest exodus Latin America has ever seen. The number is expected to increase exponentially by the end of the year.

Neighboring countries and others in the south have begun to close their borders, shut down camps or even deporting fleeing Venezuelans. Human rights violations, xenophobia, and discrimination towards the Venezuelan immigrants are occurring in an unprecedented way. Significant Latin American human rights organizations have asked all states in the region to redouble their efforts and work together in the face of the massive forced displacement.

Economic Reforms

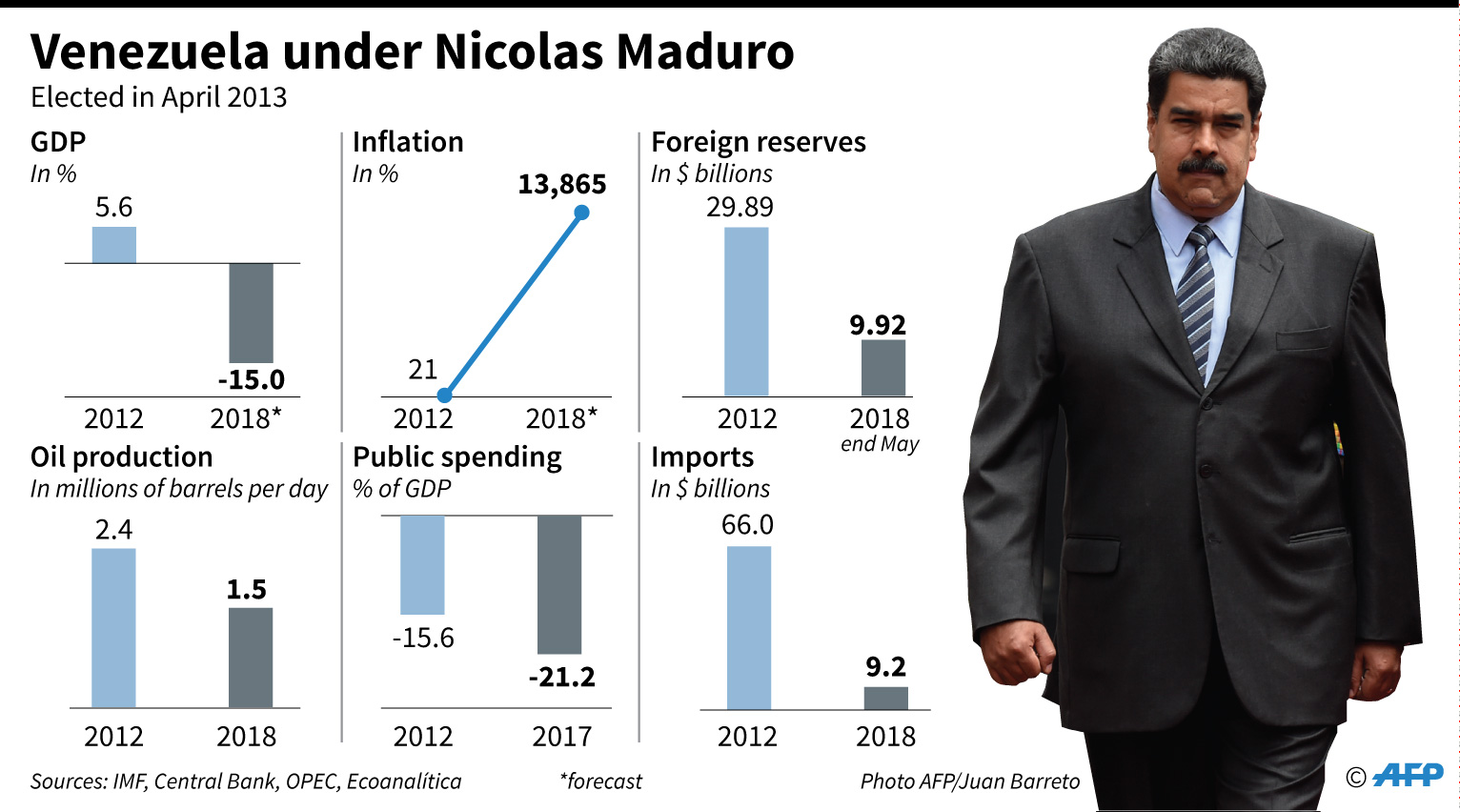

As typical for governments that live of creating narratives, complots, and conspiracy theories to cover for their corruption scandals, human rights violations, or drug trafficking allegations, Maduro’s regime has blamed the U.S. and the opposition for the dramatic economic decline that has pushed Venezuelans to flee their country. To face this situation, Maduro announced the so-called Paquetazo: the “definite economic reforms to end the economic war.”

The reforms include a new taxing scheme, the increase in wages and gas prices, eight new notes, and the elimination of five zeros of the country’s currency. According to economists, inflation could top 1 million percent following this highly complicated currency conversion. Conflict is expected to rise as people will have to pay 2311 percent more for their gas and employers will have to increase salaries by 5900 percent within weeks.

Instead of creating new hope and trust, these measures have so far only boosted the general sentiment of despair and confusion.

Shortages

The levels of shortages in Venezuela are hard to explain and digest, but let’s try to picture what citizens go through every day.

Let’s say you want to buy toilet paper. You call all your contacts and ask if they know where you can find it (you will most likely get a negative answer). Then you go out and knock on every store possible, while also constantly checking that nobody is following you, as Venezuela has become one of the most dangerous countries in Latin America with over 53 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants, about five times higher than the global average. If you’re lucky, after a few hours, you will be able to purchase a couple of rolls, provided you have enough cash (which is also scarce) or a debit card with enough funds.

Now, imagine this procedure for every single product you need to acquire. The main crux in this horror story is not “just” the fact that you cannot find goods like shampoo, milk, and bread, but that when you find them, you cannot afford them.

What does this mean? People eat less or don’t eat at all. The average Venezuelan has lost at least 15 kilos over the past year. The same scarcity occurs in medicines and medical supplies. All hospitals and now even private clinics lack basic medical supplies. The poor, whom paradoxically were the ones supposed to be protected by this so-called “socialist revolution,” are the ones who are suffering the most as they too often have to decide whether to eat or to buy medicine to survive.

Venezuelans are relying more and more on their relatives abroad. Again, for the first time, the country experiences something it only knew from the news: the need of living of remittances. For Venezuela, this once was a Cuban or Central American story that now has become their living condition.

Massive Control and Repression

People often wonder why Maduro is still in power if at least 80 percent of the population rejects him. The variables missing are control and repression. These are exerted through brute force, but also through means such as the carnet de la patria, a sort of debit card, designated to the country’s poor by which the government controls who receives food, the now subsidized gas, and most importantly, it can intimidate and mobilize its users whenever it needs to. Making citizens use the debit card gives the regime the leverage to threaten them with cutting its insignificant benefits if, for example, they do not show up to protests or elections. Now, Maduro has also proposed to transfer pension funds onto the carnet de la patria. Beyond being against any regulations and laws, this is further humiliating as it conditions pensions to political affiliations.

When walking around a Venezuelan city, one can breathe a sense of fear that is almost palpable. Furthermore, the government has successfully shut down all attempts to protest and has sent clear signals to everyone who dissents. The most recent target was elected MP Juan Requesens, who was forcefully and arbitrarily taken from his home and tortured. Like him, at least another 250 political prisoners are held hostage in the country’s abandoned prisons.

Most opposition parties, leaders, and volunteers have been attacked, banned, threatened or forced into exile.

Venezuela was once Latin America’s most established democracy but is now again under the tight control of the repressive military apparatus, which is instrumental for the regime to hold on to their power.

Desperate Venezuelans, neighboring countries, and the international community are wondering what will happen next. This question remains unanswered, but what we do know is that unpopular regimes can maintain power once they defeat the hope and actors for real change. What kind of calculus or exchanges will make the military turn against Maduro and thus open the possibility of change? That’s the question that needs an urgent answer. Otherwise, many more Venezuelans will pay the costs of something they never chose to live through.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of The Globe Post.