Press freedom is under pressure in Pakistan, where journalists face intimidation by the powerful army accompanied by violence which often pushes them to self-censure, the Committee to Protect Journalists said in a report on Wednesday.

The army, Pakistan’s most powerful institution, has “quietly, but effectively, set restrictions on reporting,” from barring access to encouraging self-censorship “through direct and indirect methods of intimidation,” the report said.

“Privately, senior editors and journalists say the conditions for the free press are as bad as when the country was under military dictatorship, and journalists were flogged and newspapers forced to close,” it added.

The deterioration comes as killings of journalists have declined, but the report links the military, intelligence, or military-linked groups to half of the 22 journalist murders in the past decade. And it says the increasing intimidation and decrease in killings are linked.

A “more cautious approach to covering sensitive topics — essentially self-censorship — accounts for much of the reduction in violence,” it cited an advocacy group as saying.

Farahnaz Ispahani, a global fellow at the Woodrow Wilson Center and a previous member of Pakistan’s Parliament, explained during the report launch that journalists in the country are forced to report only positive developments.

“While civil authorities in Pakistan also tend to use inducements and occasional threats to influence the media, Pakistan’s greatest problem is the desire of all powerful institutions of state to maintain a uniform, national narrative,” she said.

“This narrative requires journalists to report only what is deemed positive and to adhere to the very strict limits in criticizing the government or the state operators. Any criticism, for example, of the army or intelligence services is tantamount to treason,” she added.

The report gives voice to several journalists who say they have been subjected to intimidation tactics, a rarity as self-censorship grows.

One was beaten in a brazen attack in the capital Islamabad, another by what he claims were members of the security forces in civilian clothing in the southern megacity of Karachi.

“The mindset (of the military) now is to control the total narrative and reduce the diversity of opinion, so anything that is going against their narrative, they see as a threat,” agreed a director at a news broadcaster which says it has faced disruption by authorities.

“We used to feel, ‘write whatever you want’. Of course, get the facts right. Now, people are scared,” he added.

Madiha Afzal, a non-resident fellow with the Global Economy and Development Program at the Brookings Institution, said that is no longer enough to be pro-government in Pakistan, “you need to be pro-military.”

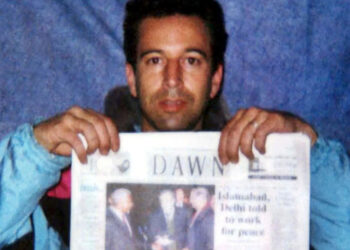

“The PTI [Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf party] has been very critical of Dawn [newspaper], for instance, because it was seen as being very pro-[Nawaz] Sharif. And so the attacks on certain parts of the media like Dawn have been compared to the attacks that the current U.S. president has made on the New York Times and the Washington Post, sort of classifying them as the enemy of the people and fake news. So it has brought on that comparison for [new Prime Minister] Imran Khan and the PTI in terms of them trying to discredit a newspaper,” she added.

Some journalists interviewed in the report noted that the definition of “anti-state activity” was not restricted to reporting critical of the army, with one journalist saying he had been threatened after writing about labor issues.

Others noted how blasphemy, an inflammatory charge that can lead to deadly mob violence in conservative Muslim Pakistan, has become another source of intimidation, with journalists censoring their reporting on religious matters.

Some 88 percent of the 159 reporters interviewed by the NGO Media Matters for Democracy claim to censor what they write or report, with seven in 10 saying that doing so made them feel safer.

The CPJ said the military had not responded to requests for comment. The army has long denied such accusations.

The CPJ report comes out a few months after a general election described as the “dirtiest” in Pakistan’s history, tainted by widespread allegations the military had fixed the playing field in favor of the eventual winner, former cricket hero Khan.

Some of Pakistan’s biggest and most powerful media outlets have claimed they were pressured to tilt their coverage towards Khan during the campaign, an accusation the military denied.

Ivy Kaplan contributed to the report

Pakistan’s Government in Waiting Grapples With Charges of Misogyny