There is no gainsaying the fact that the United States and many other western nations have legitimate grievances about engaging in trade with China. Many observers have now pointed out that the U.S. and western companies routinely face mandatory technology transfer policies, are unable to do business without first joining with local partners, and have to deal with the theft of their intellectual property. In addition, there is the issue of currency manipulation by China.

These concerns about China have existed before the advent of President Donald J. Trump and are likely to remain even after he leaves office. However, Trump is now seeking to deliver on his campaign promise to “take a stand on China” because China is “hurting” the U.S.

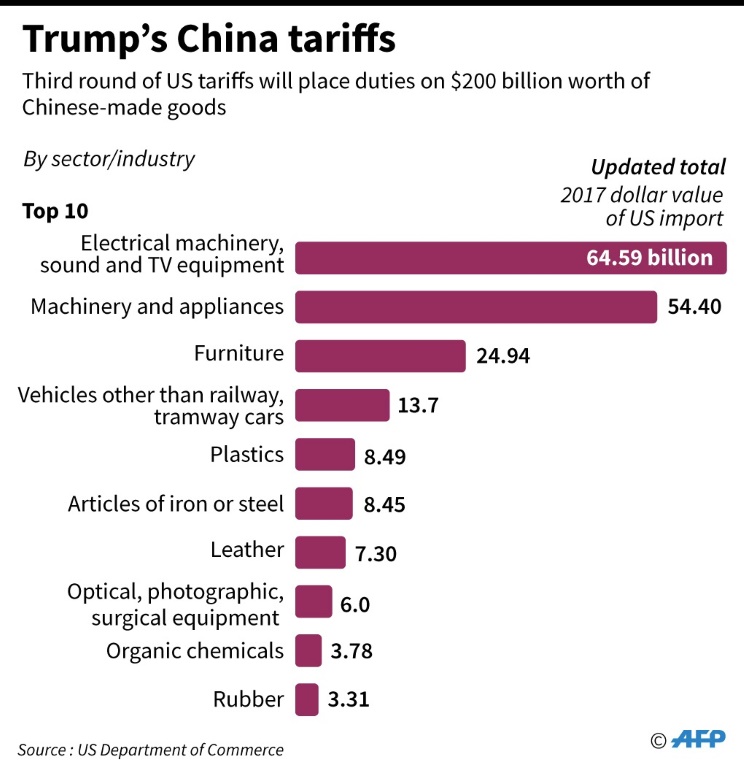

President Trump’s preferred way of taking a stand on China is to use tariffs to raise the price of Chinese goods to consumers in the U.S. and, at the same time, to offer protection to a limited number of American producer groups. With his most recent decision to levy new tariffs on $200 billion worth of Chinese goods and the promised Chinese retaliation, the two largest economic superpowers are now levying tariffs on more than $360 billion worth of goods.

The conflict between the world’s two biggest economies is already having a negative impact on both sides of the Pacific. In particular, companies in both nations are being hurt. Although U.S. consumers thus far have only felt minimal financial pain, if the present impasse continues, that may well change very rapidly.

Tariffs tend to work best when the objective is both narrow and clearly defined. Examples include a desire to raise revenue or to offer protection to a clearly specified sector of the economy. Tariffs are manifestly unsuitable when the objective is not merely economic, like trade-related, but political as well. Seen in this light, President Trump’s use of tariffs to get China to change its economic and political behavior is unlikely to work. Even if it does work, the resulting victory may well be pyrrhic.

This unfortunate state of affairs raises a salient question: given that some of his concerns about China are valid, how should President Trump have dealt with China? Let us find out.

First-Best Approach

The prominent Chinese sage Sun Tzu noted in The Art of War that “victorious warriors win first and then go to war, while defeated warriors go to war first and then seek to win.” Applied to the U.S.-China trade war, this adage means that President Trump should have thought through all of his options carefully before embarking on a potentially futile policy of levying tariffs on Chinese goods.

Specifically, since many of the problems the U.S. has are also problems that companies in the European Union have with China, Trump should have engaged in robust multilateral diplomacy with allies to enlist E.U. support for a plan involving confronting China jointly about its unacceptable behavior in the realm of international trade. In this regard, one specific action that could be taken would be to organize a boycott of China by U.S. and E.U. firms. As noted by the New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman, “the last thing Beijing wants is a U.S.-E.U. united front demanding it play fair.”

Unfortunately, this opportunity has now been missed by President Trump. Inexplicably, instead of picking a fight with one adversary at a time, Trump has decided to simultaneously pick trade fights with many “adversaries” including Canada and the E.U., entities who are our allies and hence clearly ought not to be treated as if they were our foes. Where does this saturnine state of affairs lead to? Three possible outcomes present themselves.

Potential Future Outcomes

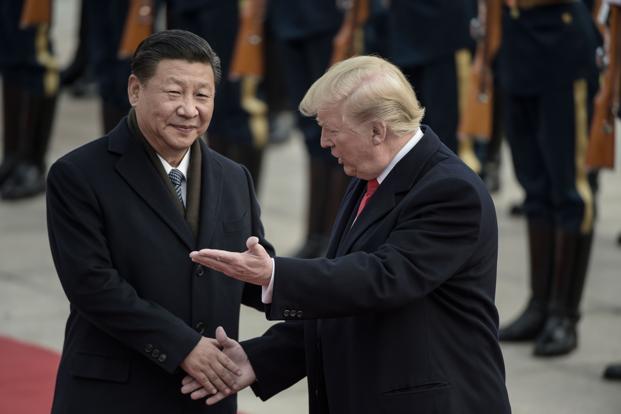

The first and the most desirable outcome would be for President Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping to instruct their respective high-level trade delegations to meet and negotiate in good faith until they can come up with an agreement that addresses the concerns of either side, particularly about the need for the trade playing field to be level. Reaching an agreement of this sort will certainly not be easy, but it needs to be done as soon as possible because the longer the current tariffs stay in place, the more likely it is that constituents for these tariffs will develop and hence they will be difficult to eliminate.

The second and most likely outcome is that the trade war will drag on for some time because neither side is willing to blink first. This is partly because of domestic considerations, and because both nations believe that they are in the stronger position and therefore can bear more economic pain than the other nation. Only when a threshold is crossed for both nations, they are likely to return to the negotiating table. The problem here is that neither country knows what the other’s pain threshold is. This outcome is likely to do temporary but not permanent harm to the current rules-based international trading system.

The third and least likely but also the most forbidding outcome would be one where the protracted trade war leads to a total collapse in U.S.-China relations across the board, and this breakdown then leads to some kind of military conflict, either over the future status of Taiwan or China’s misguided militarization of the South China Sea.

One can only hope that President Trump and President Xi now, and possibly other leaders in the future, will pay heed to Sun Tzu’s pronouncement in The Art of War that “a leader leads by example, not by force.”