Ahead of the 2018 midterm elections, President Donald Trump ramped up his anti-immigration rhetoric. His fixation on the non-existent threat of migrant crime has shifted the focus from the actual growing threat of far-right extremism.

In tweets, Trump referred to the migrant caravan approaching the U.S. southern border – comprised of individuals from Central American countries fleeing persecution and violence – as an invading force “made up of some very bad thugs and gang-members,” and claimed that open borders bring “massive crime.”

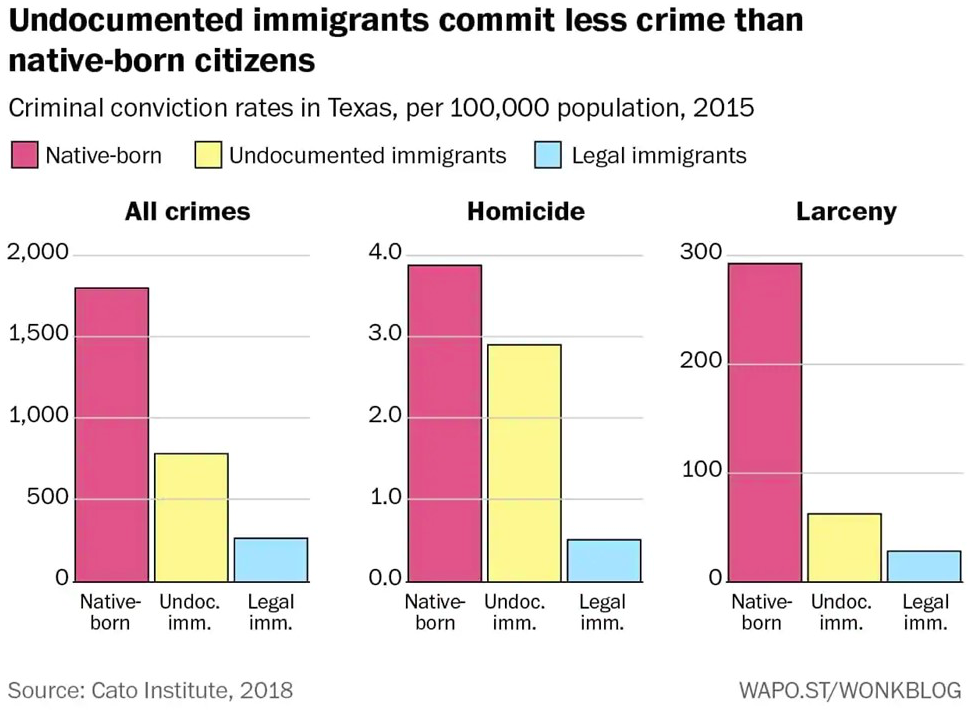

A 2018 study by the Cato Institute, however, found that undocumented immigrants committed about 50 percent less crime than native-born Americans.

Caitlin Patler, assistant professor of sociology at the University of California, Davis told The Globe Post that undocumented immigrants are not only less likely to commit crimes, a greater concentration of them actually reduces crime rates.

“There are many reasons people migrate, but the most common are due to economic instability, fear of persecution, and sometimes both,” she said.

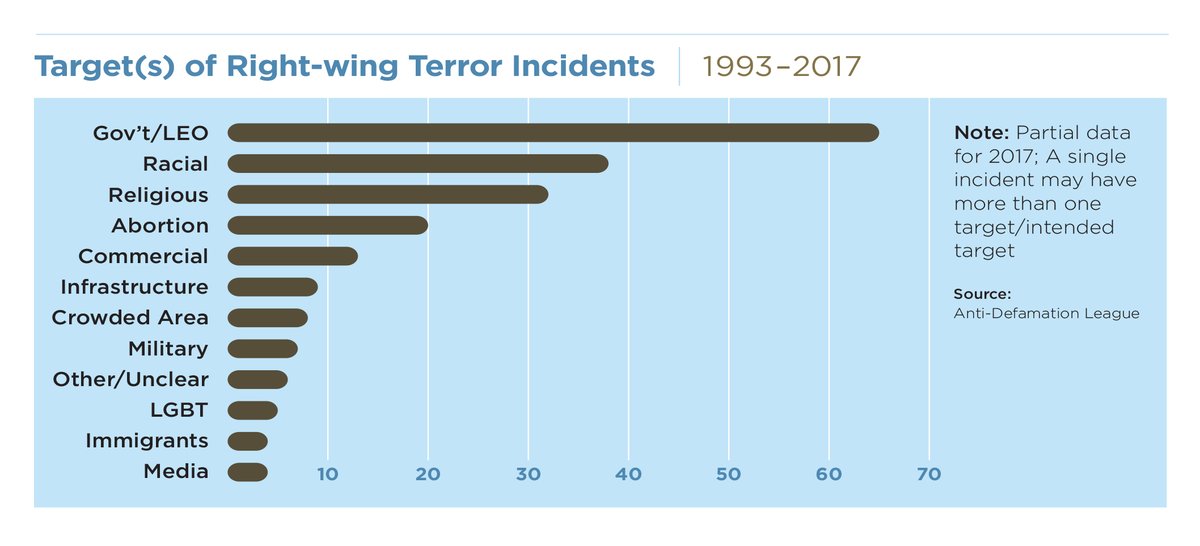

The focus of the Trump administration on the non-existent threat has exposed its failure to address the growing threat far right-wing extremists pose to public safety.

According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, far right-wing extremists are those with racist, anti-Muslim, homophobic, anti-Semitic, fascist, anti-government, or xenophobic motivations.

In the 2018 federal budget, Trump cut funding to organizations aimed at fighting far-right radical groups such as white supremacists, neo-Nazis, and the KKK. One group in particular, Life After Hate, which helps members of these groups get out, lost $400,000 in funds.

Director of the intelligence project for SPLC, Heidi Beirich, told The Hill, “I find the pattern of cutting this money to be typical for the Trump administration’s unwillingness to take seriously the threat posed by these people, whether they’re doing it intentionally or not.”

The announcement of these cuts came just before the “Unite the Right” rally that happened between August 11 and 12, 2017, in Charlottesville, Virginia, where right-wing extremists clashed with counter-protestors. One man, James Alex Fields Jr., drove his car into a crowd of counter-protestors, injuring several and killing one, Heather Hayer.

Trump eventually condemned the rally but refused to call the right-wing extremist neo-Nazis and blamed both sides for the violence that day. “You had some very bad people [on the right] but you also had very fine people on both sides,” he said.

He frequently downplays the threat of far right-wing extremists, a dangerous prospect in 2018, since the number of terrorist attacks perpetrated by far right-wing extremists doubled between 2016 and 2017, according to the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Recent events such as the sending of pipe-bombs to prominent Democrats by Cesar Sayoc and the Tree of Life synagogue shooting in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania by Robert Bowers highlight the growing trend of far right-wing extremism.

Cesar Sayoc was charged on October 29 with mailing at least 14 pipe-bombs to prominent Democratic politicians and media figures.

Sayoc – a hardcore Trump supporter – was a prolific social media poster, sharing sensationalized articles demonizing the left, pictures of himself at Trump rallies, racial epithets directed toward Oprah Winfrey and Barack Obama, and had his van decked-out with decals supporting Trump, bashing liberal politicians, and a “CNN Sucks” sticker.

Robert Bowers gunned down 11 Jewish worshippers on October 27. Bowers, also an avid social media user, spread anti-Semitic hate on the site, Gab, often reposting memes and statements targeting Jewish people. He held white-supremacist views and echoed Trump’s anti-immigration stance, referring to the caravan as invaders.

There are many routes to American radicalization, but Remy Cross, Assistant Professor and Coordinator of Sociology and Criminology at Webster University, points to two main ones: a perceived loss in status by the radicalized and online communities that hear and bolster their radical views.

“Active recruitment by groups who capitalize on grievances by teen to middle-aged white men offer them potential solutions … They seek to reframe economic or life anxieties as arising from outsiders, foreigners, immigrants, and women-and-minority-friendly policies,” he told The Globe Post.

“In this case, we’re talking about a constellation of groups, many of which have ties to older, more established white/European supremacy groups.”

According to Cross, these groups are hard to identify and stop because most of the recruitment happens in online spaces – like Gab – that are difficult to find or are completely hidden from standard surveillance and monitoring techniques.

But, the influence of right-wing extremist groups extends beyond online.

“These are groups that have made a concerted effort to infiltrate military and law enforcement over the past decade plus and have seen at least some success in these efforts,” Cross said. “This means that they often have insider information on efforts to counter them or arrest their members and that many have training and knowledge of law enforcement or military operating practices which means they know how to avoid detection in many instances.”

Of the 65 terror attacks in the U.S. in 2017, two-thirds – 37 incidents – were carried out by far right-wing extremists, according to a Quartz analysis of data from the Global Terrorism Database. Far right-wing extremism is on the rise and costing more lives each year.