Japan’s government recently announced a new policy to increase the intake and retention of foreign workers as a way to deal with the widespread labor shortage. While the policy may help some industries to alleviate the labor shortage problem to some extent, the problem will remain serious unless the underlying cause is recognized and dealt with effectively.

With respect to foreign workers, there has been a glaring contradiction between the public stance of the Japanese government and the reality. The public stance is that Japan welcomes highly-skilled foreign professionals and does not want low-skilled foreign laborers. The reality is that Japanese employers hire mostly low-skilled foreign workers via various schemes, for example by using trainees from less developed countries as workers and by hiring international students.

The new policy can be considered as an accommodation to this long-lasting reality, as it creates a new category of employment visa that can be applied by foreign trainees who have completed training and by international students who have graduated in Japan.

Although the government hastened to clarify that the new policy is not immigration policy, some of the foreign workers will manage to become immigrants via love, strategic, or fake marriages to Japanese nationals. Due to very low wages, poor working conditions, mistreatments by employers or coworkers, or the pressure of heavy debts to agents, some of them will escape to the underground economy and become illegal immigrants.

Japan’s Low Fertility Rate

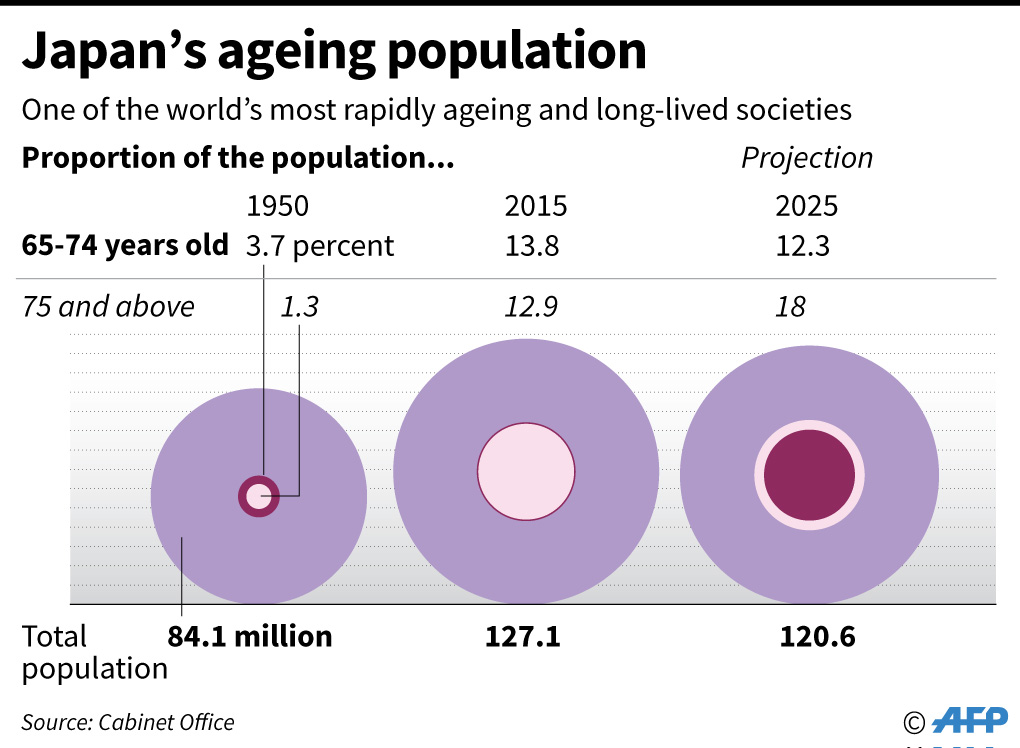

The new policy can be characterized as a small bandage on a chronically ill Japanese society. The labor shortage problem is rooted in Japan’s prolonged low fertility, that leads to a long-term decline in the labor force and population in general, while also inducing population aging. The entrenchment of the low fertility is in turn rooted in the low wages and employment insecurity of most young adults. Too many of them do not have enough income and confidence about the future to form families and raise children.

In my view, the economic hardship that young Japanese adults experience is a result of the misguided shift towards American-style capitalism by elites in the Japanese government and corporations since the late 1980s.

To increase labor “flexibility” – such as laying off or hiring workers in response to fluctuations in the demand for products – Japanese corporations have been shifting their employees from the regular category, where they had high job security and prospects of promotion, to the non-regular category, where job security and chances of promotion are lacking and wages are low. To be competitive in global markets and earn large profits, Japanese corporations suppress the wages of both regular and non-regular employees.

Problem of Corporate Tax Cuts

To strengthen Japanese corporations, the Japanese government has cut and promised to further cut corporate tax rates, while also allowing Japanese businesses to avoid taxes by hiding their profits in overseas tax havens. Even with the introduction and increase of consumption tax, the loss of corporate tax revenues has been so great that Japan’s budget deficit has become a chronic problem. In 2017, the government debt loomed to 253 percent of GDP. This huge debt effectively rules out the possibility of following the French example, where large amounts of public funds are used for pro-child policies and generous childcare provisions to improve reproduction significantly.

In 2017, Japan’s total fertility rate remained at a low level of 1.43 children per women. This is much less than the 2.08 needed for the population to replaces itself from one generation to the next. It is ironic that Japan’s recent policy on reproduction includes the promotion of three-generational co-residence as a way to increase fertility.

Even as a bandage, the increased intake of foreign workers may not be beneficial to the Japanese society. According to Professor Chie Nakane, the functional units of primary importance in the Japanese society are small, tightly-knit groups with indifference or even hostility towards outsiders, and with an internal hierarchy that accepts new members only at the bottom. For most foreigner workers, adaptation in Japan will be very difficult.

Because the top sending country of Japan’s foreign workers is China, where anti-Japan sentiments are cultivated in schools, the combination of adaptation difficulty and negative sentiment among a large number of Chinese workers increases the risk of troublesome consequences.

Although the new policy allows the long-term residence of highly skilled foreign professionals with their family members, it is unlikely that a big portion of them will actually stay in Japan, as they are prone to move on to countries like Canada and the U.S. where adaptation and the achievement of professional and familial goals are easier. The attempts of Japanese universities to increase the courses taught in English will further weaken Japan’s ability to retain them by strengthening the English skills of the foreign professionals who have entered Japan as international students and hence making them more competitive in immigrant-embracing English-speaking countries.

How Can Japan Deal With Labor Shortage?

To deal with the root cause of the labor shortage, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe should not follow President Donald J. Trump’s example of cutting corporate taxes. Instead, he should take the advice of Professor Mitsuharu Ito, and raise corporate tax rates and the tax rates of high-income individuals, both of which are unlikely to undermine domestic demand and hence economic growth.

In the meantime, Japanese corporate elites must keep the long-term interest of the Japanese society in mind. It is important that they return the profits hidden in foreign tax havens to Japan, raise the wages of employees, and offer better job security and prospects to young Japanese workers.

It is helpful to remember that the employees well cared for by the Japanese corporations in the 1960s were quite hardworking, productive, and innovative. The tightly-knit functional groups of Japan automatically suppress laziness and instill the spirit of ongoing improvement. Excluding young Japanese adults from these groups as non-regular workers inflict serious harms on not only these young adults but also the whole society.

The inability to deal with the problem of very low fertility over the previous decades forces Japan to rely on large intakes of foreign workers for about two more decades, even if the fertility is immediately raised to the replacement level.

The urgency of raising fertility effectively and recognizing the causes involved should be clear.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of The Globe Post.