Consistent with public feelings, the Japanese government has long maintained that they will not allow foreigners with low skill levels to work in Japan. However, a newly passed immigration control law reverses this position and explicitly permits these workers to work in Japan using a new level 1 visa category. The bill passed the Japanese parliament in December in a reaction to pressure from many sectors that claim labor shortages.

The level 1 visa is to be granted to foreigners with less technical skills and is not renewable beyond five years. In contrast, workers with high skill levels in specific fields will be granted a level 2 visa that allows them not only to accept jobs but also to bring their family and live in Japan for up to five years. This visa is renewable and can ultimately lead to permanent residency.

Those hired in the low skill category, however, are not allowed to bring their family members to Japan. This restriction based on skill level is reminiscent of policies of past ages that denied basic human rights to those in lower social classes.

Saving Public Money

The government’s primary intention in creating this constraint appears to be saving public money that otherwise would have to be spent on these foreign workers’ and their families. If allowed to stand, the restriction seems destined to become a cause for domestic and international advocates of human rights and a likely source of public outcries. The restriction might spread a picture of Japan as a nation uncaring about human rights for those who are not Japanese.

The foreigners who are currently in the old government-sponsored skill training program will be allowed to move into one of the two new visa categories if they can pass certain skill and Japanese language tests. The reason these workers might want to make this move is that the government maintains that the workers in the new visa categories will receive wage compensation that, by law, will be in line with their Japanese counterparts.

In practice, however, under the old skill training program, foreign workers have mostly received wages that are considerably below market wages (with the lower salaries sometimes justified as “training wages”). Foreign workers are also often believed to have working conditions that are poor compared to Japanese nationals doing similar jobs.

Serving Industry Needs

The two new work visas are intended to serve industry needs for hiring high and low skill foreign workers. It is the industry that is pushing for this revised visa program.

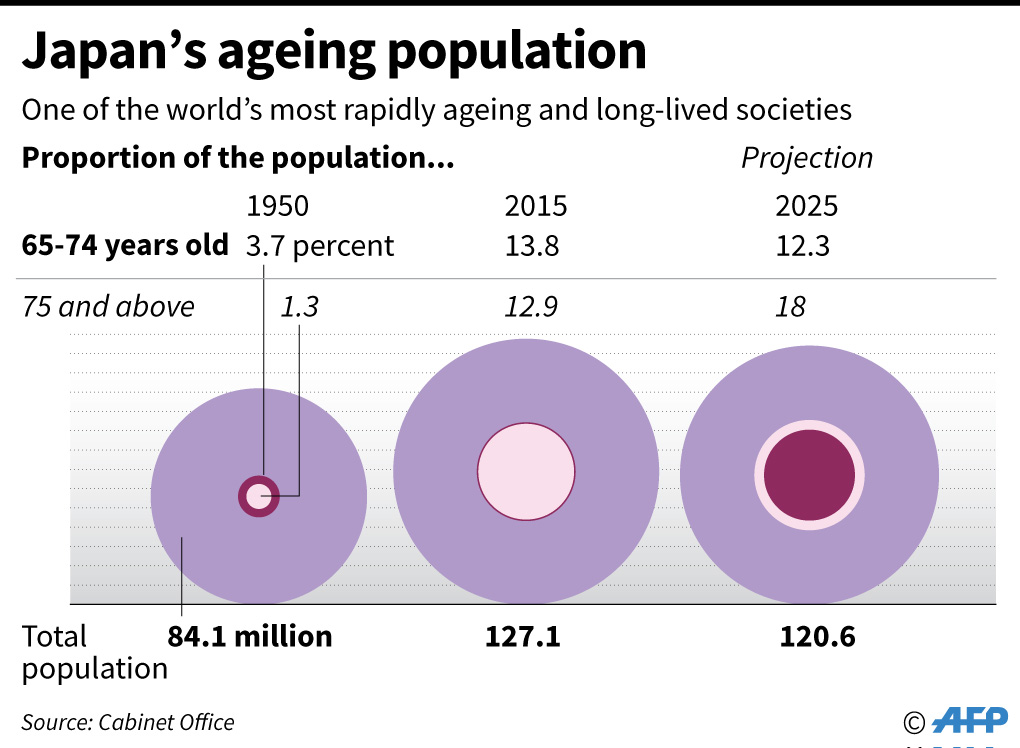

Since the Japanese working age population has been declining steadily and the nation is highly aware of this, the public appears sympathetic towards accepting foreign workers but seems to have concerns that the welfare and living conditions of the foreign workers won’t be satisfactory.

The opposition parties generally agree with admitting foreign workers but are especially focused on issues related to Japanese language capabilities, working conditions, family welfare, and integration into Japanese society.

The government’s discussion of the new law, so far at least, lacks recognition of the importance of social issues that inevitably arise when a nation seeks to solve an economic problem by bringing in workers from other countries.

It is well known that the Japanese government and public want to maintain the nation’s social stability and cohesion. If so, the government needs to ensure adequate budget, administrative, and other program delivery arrangements for proper care of immigrant workers and their family members.

Expected Labor Shortages

The government estimates that Japanese employers will hire up to 345,000 foreign workers in mostly high skill level categories in the next five years. However, the low skill visa category would not exist were it not for expectations of shortages for those types of workers too.

Moreover, for the coming 5-year period, the Japanese economy is predicted to be short of about 1.45 million workers. The proposed number of foreign workers expected to come under the new visa programs is still considerably below the amount the Japanese economy needs.

It has to be asked whether domestic policies could and should be adopted instead of, or in addition to, the new law to deal with the shortages. The answer to this question will be revealed, in part at least, by the outcomes of multiple ongoing government initiatives, including subsidies for child care, efforts to raise Japanese labor productivity, and improved access to employment for those who were previously working and but had to quit for reasons unrelated to job performance.

These policies are aimed at increasing the domestic labor supply and have been undertaken as an integral part of Japan’s economic growth strategy. These measures should continue, as many view them as important for reasons beyond the labor shortage that motivated the new immigration law.

However, given the observed effectiveness to date of these policy initiatives regarding labor force expansion, it seems unlikely that they will eliminate the labor shortages over the next five years.

With the recent passage of the new immigration control law, this reality has been implicitly recognized by industry and government leaders. The key challenge now is to implement the new law in a way that does not cause a public backlash and does not invite international condemnation on human rights grounds.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of The Globe Post.