We know the story of Huawei, and some of us, although not all of us – which is one of the story’s many equivocal aspects – know its crime. This alleged crime began in 2003, when tech company Cisco sued it for intellectual theft, an indictment of over 70 pages filed at a district court in Marshall, Texas.

This fairly typical small town of Marshall is also unusually popular for patent suits because of its conservative court, best known for its speedy judges and plaintiff-friendly juries that historically favor patent holders 78 percent of the time, compared to the 59-percent average win rate nationwide.

A year would pass, and the federal court still would not be able to come to a decision. The suit ended in July 2004 with a mutual settlement: Cisco and Huawei would be responsible for their own attorney fees, and Cisco could never again bring the same claims against Huawei.

Huawei subsequently turned paranoid. It has since set aside a minimum of 10 percent of its revenue for research and development and, in 2018, pledged to increase this spending to as much as $20 billion, a magnitude similar to that of Amazon ($22.6 billion in 2017) and Google ($16.6 billion the same year).

In 2017, Huawei filed some 2,398 patent applications with the European Patent Office, making it the biggest filer of patents in Europe.

Accusing Huawei

When Huawei is not being accused of stealing technologies, it is said to be spying for China, acting as “a potential conduit for espionage and sabotage.” Bloomberg Businessweek reported in October that “the Chinese People’s Liberation Army had planted chips in server motherboards manufactured in China” to conduct “The Big Hack,” infiltrating “Amazon and its Amazon Web Services, Apple, the FBI, the Defense Department, the White House, and unnamed companies.”

Bloomberg based the specifics of those allegations on “more than 100 interviews” with “17 individual sources.” No other news outlets, however, were able to corroborate the investigation, even though it was claimed to have affected nearly 30 U.S. companies.

Apple wrote in a public statement that the firm “has never found malicious chips, ‘hardware manipulations,’ or vulnerabilities purposely planted in any server.” Amazon dismissed the report for having “so many inaccuracies […] that they’re hard to count.” Director of National Intelligence Daniel Coats said he had seen “no evidence of Chinese hacking.” Rob Joyce, an NSA cybersecurity official, would like to see anyone who “has first-degree knowledge [and] can hand us a board [and] point to somebody in a company that was involved in this, as claimed.”

Throughout “The Big Hack” controversy – the centerpiece surrounding the fear that the Chinese could insert “back doors” into telecom and computing networks – Huawei had not been named once.

Huawei’s Big Picture

Some say these details are unimportant, that the “big picture” is the same no matter which reportage you choose to believe – that Huawei was founded by Ren Zhengfei, a former People’s Liberation Army engineer, and by extension, Huawei’s ties with the Communist Party are unshakable.

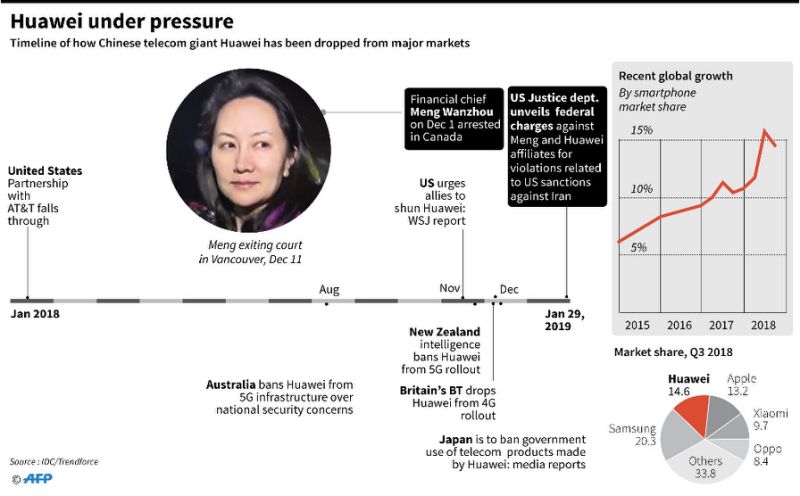

The arrest of Sabrina Meng, the 46-year-old daughter of Huawei’s founder, who until now had maintained an “exceptionally low profile,” should therefore not come as a surprise.

She is wanted for extradition to the United States for violating the U.S. sanctions against Iran, though the charge has now been shifted to defrauding banks. She is scheduled for a hearing set in Vancouver on February 6. And yet, the case seems already settled, in terms of the purpose behind it and the outcome desired.

Bloomberg warned that solid evidence against Huawei for the claims of espionage “has been lacking,” and so “it’s not a slam dunk.” It occurred to me then that comparing a judiciary procedure to a slam dunk for something that is yet to be on trial only makes sense when the predetermined outcome so earnestly sought after by the plaintiff is all too clear for everyone.

Going further is a headline from the Wall Street Journal that reads “The U.S. believes it doesn’t need to show ‘proof’ Huawei is a spy threat.” Not without a touch of irony, Democratic congressman Tom Marino wrote back in October to U.S. energy secretary Rick Perry – a former CEO of Exxon Mobil – that Huawei’s cheaper solar panel technology “may pose a threat to our nation’s infrastructure.”

Whether Huawei’s founder’s daughter Meng is extradited on the alleged bank fraud or not, I also remember how other corporate shenanigans have routinely been treated as nonevents

White-Collar Prosecutions

Another report by the Wall Street Journal examined the 156 criminal and civil cases brought forth by the Justice Department, the Securities and Exchange Commission, and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, which had led to the worst calamity to hit the American economy since the Great Depression.

The government did not charge or identify individual employees in 81 percent of these cases. Among the remainder, some 47 low- and midlevel employees were prosecuted, with only one boardroom-level executive being sued civilly.

That no top bankers from the leading financial firms – Citigroup, Wells Fargo, Morgan Stanley, J.P. Morgan Chase, and Bank of America – went to jail for the widespread wrongdoing despite the bank bailouts was evidently a general shift away from white-collar prosecutions.

In 2016, the Department of Justice brought just 6,200 cases against individuals, the lowest number in two decades, down more than 40 percent since 1996. The number of white-collar prosecutions is on track to hit a 20-year low under President Donald J. Trump.

Prosecutors, in other words, prefer settlements over prosecutions, with companies forking out money while reporting record-high profits. Set against this trend is the latest corporate officer in question, from Huawei, who happens to be a woman from a foreign power.

Economically Disengaging China

The mulling over an executive order by the White House to declare a national emergency that would bar all U.S. companies from buying equipment made by Huawei is no skirmish over compliance with the sanctions against Iran. It is a battle over the national dominance of critical technologies in the age of connectivity and smart machines.

When people in Washington or the Pentagon are talking about the importance of banning Huawei from the United States or forbidding U.S. companies like Qualcomm and Intel from selling products to Huawei, they are talking about something that is harder to advocate, at least openly in public: disengaging China economically.

But no disengagement today is truly genuine in our globalized economy. It is too late: just about everybody, including Cisco, Ericsson, and Nokia, is making telecom equipment in China these days – hence the origin of Bloomberg’s much-discredited story on The Big Hack.

Chinese manufacturers and designers have long been an integral part of the global telecom supply chain. Blocking Huawei from the United States, while allowing other equipment branded by Cisco and Ericsson and sourced from China, may make a few politicians feel good. However, disguising the reliance of American and European manufacturers on Chinese subcontractors does not eradicate any security concerns that these politicians have so fervently raised.

Calling it by the Name

Language can erase, distort, mislead, and cast out decoys and distractions. The worst lies are half-truths, created by omitting crucial information, or unhitching cause and effect, or using names as euphemisms to mask something awful or invent conflicts where there are none.

“The enemy of clear language is insincerity,” novelist George Orwell once wrote. Precision, accuracy, and clarity in language matter.

Perhaps these factors matter even more so in a world where a “national security threat” suddenly involves everything that is being imported, from telecom equipment to steel and aluminum.

To call something what it truly is – protectionism, isolationism, nostalgia over a nonexistent past – is to lay bare what may also be untenable.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of The Globe Post.