Former President of Sudan Omar al-Bashir has been placed under house arrest by his own military, ending 30 years rule of one of Africa’s most notorious and long-ruling strongmen. But like so many countries that have experienced long term authoritarianism, fundamental questions remain. How did we get here and what is next for Sudan? What are the challenges ahead and how will the international community engage with the “new” Sudan?

Staying Power of Al-Bashir

Coming to power in 1989 via a military coup, Bashir had long mastered the art of political survival. Many challenges to his position emerged either by internal competitors, civil society, opposition or even external forces. Each time though, the 75-year-old weathered the storm through sheer political brinkmanship or violent brute force.

Notorious is the civil war in Darfur in western Sudan, where Bashir applied a scorched earth policy to extinguish dissent. The International Criminal Court indicted him later for these crimes against humanity.

Bashir was known for imprisoning opponents, exiling perceived and real enemies, and cracking down on any dissent to his rule. Simply, he led with an iron fist.

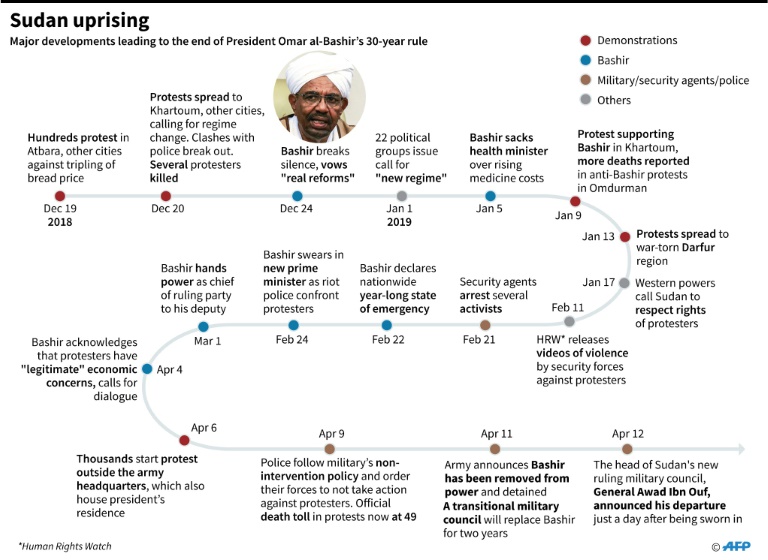

This explains his 30 years of incumbency. The crisis that finally felled his regime was as unexpected as was its ultimate end. The casualty of 60 protesters, hundreds more injured, and countless incarcerated were evidential of another Bashir playbook tactic.

The state of emergency and the compromise to dismiss his government were steps too little too late. He lost his last roll of the dice.

Elites Bring Fight to Bashir

In democratic transitions, nothing happens without the role of elites, whether within the status quo or opposition.

In Sudan’s case, it was the military elite and allied civilian patronage network that kept Bashir in power. However, with growing disquiet from elites outside the political network and subsequently the co-optation of elite insiders, Bashir’s fate was sealed.

First, the Sudan Professional Association comprised of teachers, lawyers, doctors, and engineers became a critical organizational force in sustaining the growing protests. They provided planning and a focused message that resonated with everyday folks on the street. This gave the demonstrations broad public appeal while also fueling its persistence.

Sudanese Professionals Association says it will continue sit-in until the establishment of a civilian government #Sudan https://t.co/RraOX0j74f

— Isma'il Kushkush (@ikushkush) April 14, 2019

Second, the internal elites and especially the military read the writing on the wall. Like many elites in Algeria, Egypt, Tunisia, and Zimbabwe who all seek self-preservation, the military did have a sacrificial lamb: their commander in chief Bashir.

Political and Economic Challenges

Sudan has experienced significant political and economic challenges under Bashir, and the current crisis is a direct offshoot of this. High levels of inflation, unemployment, and general deterioration of opportunities with a persistent civil war in Darfur all had a damaging and lasting effect on the nation.

Ultimately though, like during the Arab Spring, the ailing economy has proven to be the Achilles heel of long-term strongmen yet again. Evidently, fixing the economy that has suffered from years of mismanagement and falling oil prices is an immediate concern, as are the socio-economic challenges that gave rise to the uprising in the first place.

Going forward, Sudan’s system needs rebooting, institution building, and fundamental reforms to guarantee civil and political rights, the rule of law, security, and political stability, particularly in the Darfur region. Bedeviled by systemic corruption, transparency and accountability are key.

Future of Democratic Transition

The events following the deposing of Bashir were symptomatic of the confusion and often broad uncertainty that follows after long-term authoritarianism.

In Sudan, the euphoria that followed Bashir’s downfall was quickly replaced by the despondency that the military will oversee the transition period for the next two years. And for “good measure,” the military suspended all constitutional orders and instituted a state of emergency declared.

It immediately was apparent that this was not fundamental change but rather a change of guards.

With the protesters remonstrating and refusing this power grab, the military saw the resignation of the new head of the military council only a day after he was sworn in, and a broad call to the civilian opposition to participate on a transition roadmap. The opposition has also been urged to name a prime minister who will work with the military to realize fundamental political reforms.

The key question remains: will Sudan realize a genuine transition and if so, how?

The transformational journey is certainly not going to be easy or straightforward as other cases of regimes emerging after long term authoritarianism show. But the removal of Bashir is the first step of change.

It is highly unlikely that any new leader can harness a patronage system to serve their interests in the same way that Bashir did. To that extent, change is guaranteed.

The military too is very self-interested and has an eye on preserving their interests in the new dispensation. As such, they will be as pragmatic and shrewd in safeguarding their interests through compromise with the civilian elites and traditional opposition without jeopardizing their strategic interests.

Make no mistake, the military monopoly on the use of force is still perceived as an existential threat to any civilian regime in Africa, and hence the civilian elites are likely to offer a fig leaf to the men in uniform: compromising rather than antagonizing.

International Community: Rapprochement

Sudan’s coup came at a momentous time. Most recently, the country was slowly shedding its pariah status as a “state sponsor of terrorism,” re-engaging with Washington and rebuilding its place in the international community “after” Darfur.

For the international community, the general chorus has been one of welcome change, urging a quick, steady, and transformational reform towards democratic governance, the rule of law, and having Sudan as a responsible international partner.

Sudan will receive a lot of goodwill from the international community in its transformation effort. Agitation to subject Bashir to the International Criminal Court undoubtedly persists, but above all, Sudan will find eager and supportive partners on the global stage.

For Sudan, it’s about making the best of a fresh start.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of The Globe Post.