In the words of the renowned linguist and public intellectual Noam Chomsky, “the American criminal justice system is an international scandal, both in its scale and its brutality.”

The U.S. incarcerates its citizens – disproportionately those of color – at the highest rate of any nation in the world. Many of those people, including juveniles, languish in solitary confinement despite an abundance of evidence that the practice can cause devastating psychological trauma.

From Fergusson to Baltimore to South Carolina and beyond, the high profile police killings of unarmed black men have also thrust the issues of state violence and police brutality into the broader national consciousness.

As Chomsky writes in his praise for the new book, “Beyond These Walls: Rethinking Crime and Punishment in the United States,” these issues “are rooted in a much broader range of ‘social control institutions,’ matters investigated with penetrating insight and historical depth in this powerful study.”

In a two-part interview, The Globe Post spoke to the book’s author Tony Platt, a Distinguished Affiliated Scholar at the University of California Berkeley’s Center for the Study of Law & Society, about the history of mass incarceration in America, what’s missing in our current conversations about criminal justice, and how we as a society can rectify the injustices that are pervasive in our current system.

The interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Q. In recent years, there’s been a lot written about the criminal justice system in America and about mass incarceration. When you set out to write this book, what did you feel was missing in the discourse? And what was it that you wanted to contribute to the literature on the subject?

Platt: Well, I started thinking about this book a long time ago in the 70s when I was part of social movements and activist movements to try to change the criminal justice system. And that was at a time when there were all kinds of activists at work – from liberal Democrats to community activists, the Black Panther Party, people working to try to reduce the prison population and so on.

One of the things that we found then, at the height of social movements for justice, was the incredible resistance to making any kind of significant changes. So that was an issue that I’ve thought about for a long time. Why is it that even when there’s a tremendous amount of activism and support for social justice – for example in the 60s and early 70s getting rid of capital punishment, closing juvenile prisons and so on. But it was so difficult to change things.

I didn’t return to this issue really until maybe seven or eight years ago during the Obama years when there was both a revival of movements for social justice around gun issues, around prison issues, police killings and so on. The Obama administration also created a political, cultural space for national discussions about what to do. So I thought that was a good moral moment to return to this issue. And also I was struck during the Obama years, despite the protests on the streets and despite the government commissions and task forces, that also there was very little change as well.

So my interest in the book was trying to look at the stubbornness and resistance to change and to try to think through more deeply why change is so difficult and what it will take to do it.

Q. You write that Beyond These Walls is “a dynamic genealogy that zigzags in time, searching for persistent patterns and ruptures in history.” What were some of the most persistent patterns that you ultimately identified throughout the course of writing the book and what do you think those patterns tell us about our present moment?

Platt: One of the consistent patterns is that the criminal justice system doesn’t do a good job either protecting people from crime or imparting justice, despite its name. As long as criminal courts and police and prisons have been operative, most people don’t report crime to the police and most people don’t have a lot of confidence that the police or the courts will actually help them.

Secondly was the systematic injustice of the so-called criminal justice system. The injustices work in a couple of ways. They work internally by the fact that the side of the prosecution has so much going for it. We’re supposed to have an adversary system where you have this balance of forces – defense and prosecution equally weighed against each other. But most personnel – over 90 percent – work on the side of prosecution and very few public defenders, probation officers, and parole officers work on the side of the defense.

Because of a bail system that rewards people with money who can get out of jail while awaiting trial, millions of people go through the criminal justice system who are impoverished and awaiting trial in jail and therefore in a sense are forced to plead guilty. Another example of the internal injustices would be the different ways in which people can defend themselves. If you have money and resources you can have private lawyers which really increase your chances of getting acquitted or minimizing your sentence. And if you don’t, then you rely on public defenders who are incredibly overworked and pressured to get their clients to plead guilty and can really not do very much except maybe reduce sentences for some people.

So that’s the way the internal injustices work. And then I also recognize along with many other people the external injustices, which have to do with the way in which the criminal justice system tracks out of courts and prisons and jails – tracks our corporate and state criminals who commit usually massive economic crimes and who get treated in a totally different way. They rarely end up in prison or jail. They rarely end up in jail awaiting trial and mostly they end up paying fines which are not very much given the resources they have.

Think about the bank HSBC that was investigated and then prosecuted for processing the illegal funds of drug cartels from Mexico and were found guilty of that and ended up being fined. Or Wells Fargo Bank that defrauded thousands of customers that ended up being fined. So you have this system of injustice that works externally by tracking corporate and economic criminals out of the criminal justice system into really a kind of civil litigation. So that was a persistent pattern over the years that I recognized.

Another thing is that the criminal justice system historically plays a very key role in going after social movements and organizations and individuals engaged in struggles for social justice and equality. But it’s not just police and prisons that we’re talking about. There’s a wide variety of other actors – government officials, public health officials, social workers, teachers. If you look at the history of campaigns against different social movements and social groups you see a wide variety of actors involved, not just police and prisons.

“I think of the criminal justice system operating more like a population control institution than a crime control institution.”

Q. Very early on in the book, you introduce us to the case of Edward Streiff and Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor’s dissent in that case. Why did you decide to start out with that anecdote and what is it about Sotomayor’s dissent that you found to be so important or illuminating?

Platt: One is that she made a very powerful personal statement which is unusual from a Supreme Court justice. She talked about the injustices of racism in the criminal justice system – the discriminatory approaches of the police and patterns of policing and so on. And she drew upon a literature that a lot of people read that are critical of the criminal justice system that usually is not cited by Supreme Court justices. Literature by Michelle Alexander and other journalists and writers who have talked about systematic patterns of discrimination and racism. She said this part of the dissent is coming from a very personal place. So that was unusual and I thought very powerful and very moving.

Secondly, she used the word “carceral,” which I wanted to use in this book and wanted to introduce early on because I think “carceral” suggests something much wider in terms of institutions of social control than just police and prisons and sheriffs. She talked about the way we live in a society in which carceral institutions catalog and regulate and control populations.

I think of the criminal justice system operating more like a population control institution than a crime control institution. And I thought her term her use of the term carceral – given that I wanted to use it – was a good way to introduce the term.

Q. Sotomayor’s line about certain people not being so much “citizens in a democracy” as they are “subjects in a carceral state, just waiting to be cataloged” reminds me of what life was like for African Americans in the South in the post-Reconstruction period under the Balck Codes. For people who aren’t familiar with that history, can you describe what the criminal justice system of that period was like, particularly in the South, and in what ways it’s similar and different to what we have today?

Platt: So after the Civil War and the freedom that was achieved by the formerly African slaves in the United States, this period called Reconstruction was really the first moment of the American civil rights movement that doesn’t really begin to be completed again until the 1960s. It’s a 100 year period between Reconstruction and the civil rights struggle of the 1960s and the legislation that was passed then. Reconstruction was a moment in history where considerable civil and social and political rights were granted to African American people that they won through that particular struggle.

But then they were weakened once the federal troops and the federal government withdrew from the South and the South sort of reclaimed its old patterns of racial segregation and racial humiliation. Reconstruction was defeated. And one of the vehicles for both reducing the status and criminalizing the status of African American people – and also drawing upon the labor force that would play a critical role in the economic revival of the South – was to use these special measures.

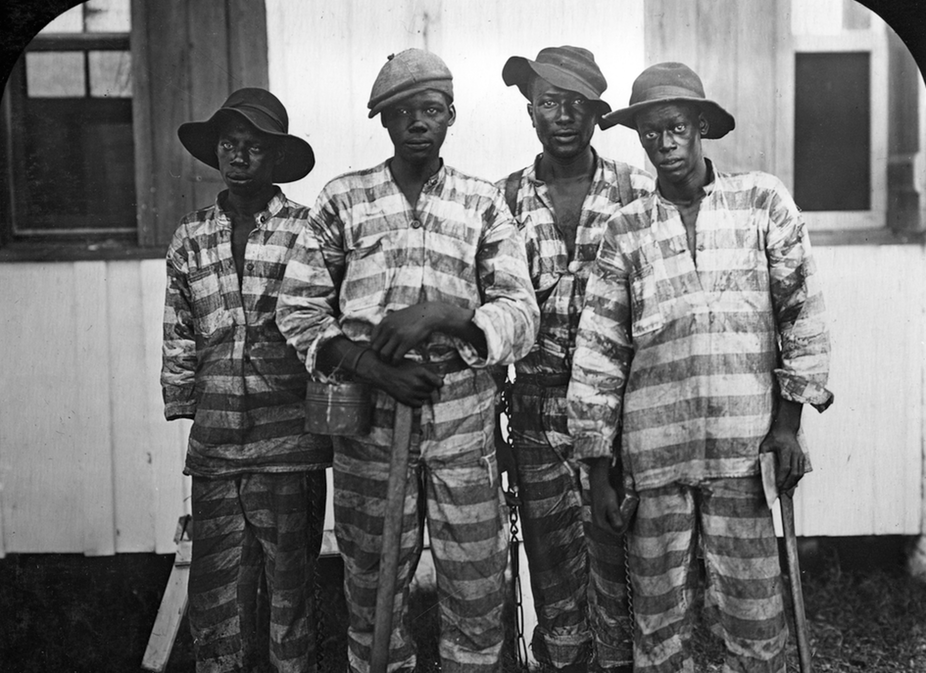

First of all was the convict lease system, which basically allowed sheriffs and police and local authorities to round up free people on the streets – not on the basis of any crime, just basically being free and not being able to see that they had a specific job somewhere. Tens of thousands of people were then rounded up that way. And they didn’t end up in prisons and jails. The South during the latter part of the 19th century had very few prisons actually because they were then literally sold. The state would sell them to private employers.

That was followed later on when the state began to get involved in this business of exploiting prison labor through the chain gang system. Prisoners were actually arrested and, instead of being incarcerated, were put on chain gangs and set up to build roads and other parts of the infrastructure of the South. That system was extremely brutal.

Today, when people talk about mass incarceration being a recent phenomenon, I think they fail to recognize that this was really a carceral institution. True, people weren’t put in buildings, but they were literally chained to their private employers and were worked to death at a rate that was quite extraordinary. Sometimes more than 30 percent of the labor force was destroyed. It was injured and was killed by this experience. And that continued until the Great Migration from the South, when millions of people fled the South to the North and the Midwest and other parts of the United States.

So that was a time of entrenched institutionalized racism. Some people talked about that system actually being worse than slavery in the sense that at least under slavery, slave owners had an interest in trying to keep their slaves alive because of the value of the labor force. Because there was so much surplus labor after the defeat of Reconstruction, people’s lives didn’t mean very much because they could be easily replaced.

But I think it’s important to note – and I try to make an issue of this in the book – that this was also being replicated in other parts of the world. For example, sending convict labor to Australia and the British colonies. And there are other examples of this from other Western capitalist countries. In the United States, you have really the equivalent of the Black Codes taking place on the west coast after genocide and the defeat of the native tribes. You had exactly the same legal criminalizing process of people who were basically unemployed were fair game to be picked up and criminalized. So native peoples on the west coast – particularly women and children – were sold into slave jobs in people’s homes and fields and ranches.

Women were often sold into rape and sexual subservience. In family homes, children were taken from their families and sent all over the place. So the extent of it in the South that happened to African Americans was really massive. But it’s important to understand that this had precedence elsewhere in the world and also that there were other parts of the United States where this was taking place as well.

“Racism is not just a carryover from the past or the debris of the past. It’s also constantly reinvented.”

Q. I know you write too that today’s system is less so geared around exploiting labor then it was in those days. But do you find any similarities to the present moment when you go back and read that history?

Platt: Well I think we’ve got to be careful about seeing that what’s happening today as just a continuation of the past – that this is just Jim Crow and new forms of slavery. One because this happened to many many different kinds of populations. It happened to the Chinese on the West Coast. It happened to white European members of the labor movement on the East Coast and in the middle of the 19th century. So African Americans are clearly central to this form of exploitation and criminalization but there’s also many other examples as well. So in that case, I think we have to be careful.

Secondly, there are clearly similarities in terms of the racial dynamics. Treating people as though they’re different and inferior and humiliating people and treating whole populations as though they’re racially distinct and racially inferior – that echoes what happened in the South after the defeat of Reconstruction.

But also I think it’s important to understand how racism is not just a carryover from the past or the debris of the past. It’s also constantly reinvented. The racism of the urban North – beginning after World War II – the kind of racism that targets populations of color in major cities the urban areas has a very different dynamic and a very different process than the racism of slavery or the racism of Jim Crow.

I think this is important because this is a way to understand how racism is a dynamic process. It changes, it takes new forms that are reintroduced in new ways and we’re not just seeing something that’s a continuation of past forms.

More on the Subject

Beyond These Walls: Social Control and Criminal Justice in America [Part II]

![Beyond These Walls: Social Control and Criminal Justice in America [Part I]](https://theglobepost.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/US-prison-968x570.jpg)

![Beyond These Walls: Social Control and Criminal Justice in America [Part I]](https://theglobepost.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/US-prison-350x250.jpg)