After 20 years of uninterrupted circulation, the Basque daily Gara faces its biggest challenge yet: overcoming political and judicial persecution imposed through the collection of an “ideological” debt.

The story begins in 1998, about half a year before Gara’s foundation, when Spanish judge Baltasar Garzon closed the Basque radical left-leaning daily Egin on charges of belonging to and being controlled by the terrorist group ETA.

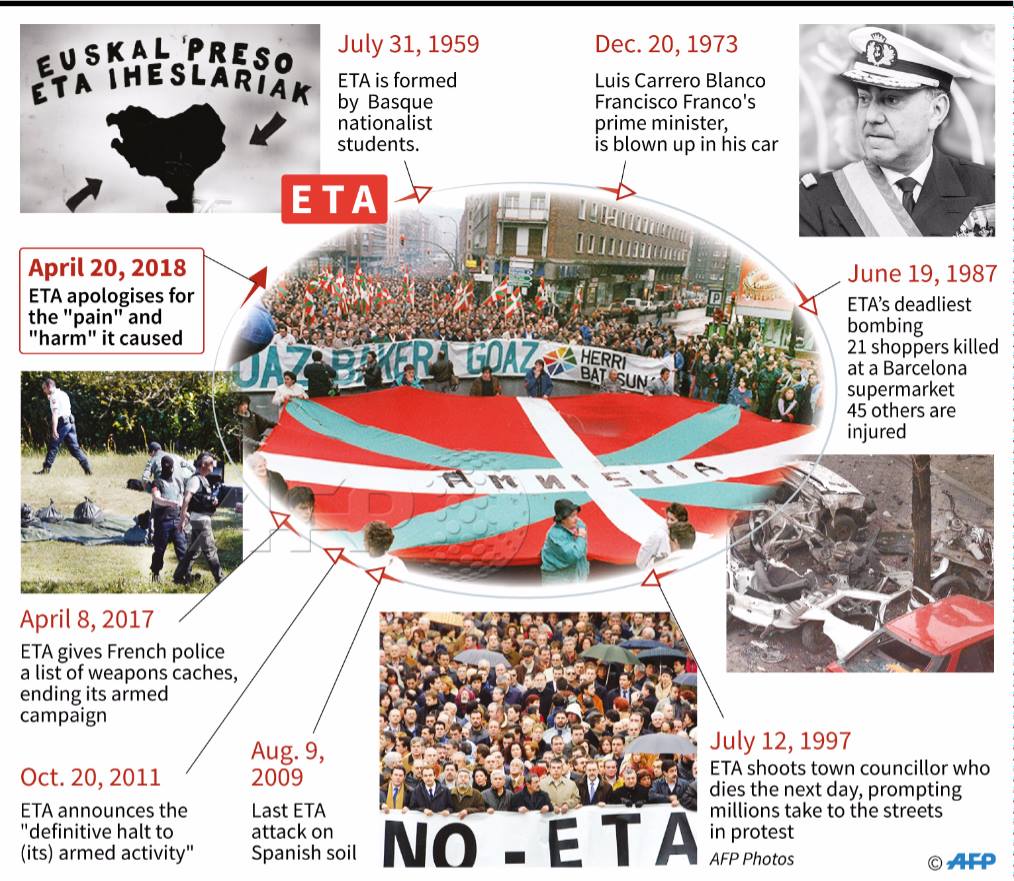

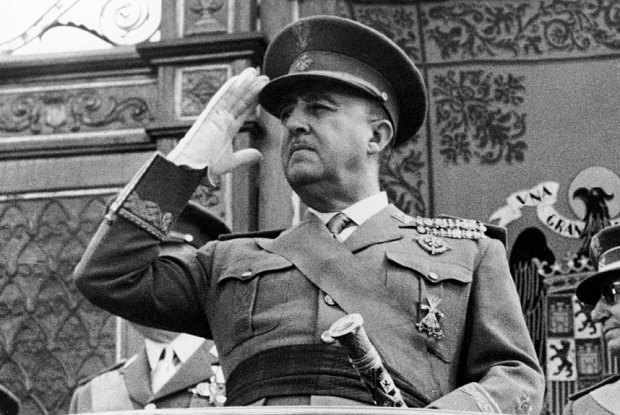

The conflict between Basques, an autonomous community in the north, and Spain is not new. It became more intense during the years of Francisco Franco‘s dictatorship (1936-1975) when the Basque people were harshly repressed and their language and culture were persecuted.

During this period, the ETA group was founded, carrying out a series of attacks in Spain with the aim of gaining independence for the region. With the arrival of democracy, the group continued its attacks – as well as policies to criminalize Basque social and political movements continued to exist. With the dissolution of ETA in May last year, a change of scenery was expected. This is not what happened.

Basque Newspapers Egin and Egunkaria

Egin was founded in 1977 amid Spain’s incomplete transition to democracy. The newspaper aimed at giving a voice to the Basque left fighting for independence. In 2009, eleven years after the forced shutdown, the Spanish Supreme Court acknowledged that the closure was illegal.

However, the paper’s journalists continued to be in jail, accused of being under the control of terrorist organization ETA. Egin’s editor Javier Salutregi remained imprisoned until 2015 for the crime of being a journalist and for having an ideology opposed to Spanish interests.

Egin’s story is similar to that of Egunkaria, another Basque newspaper published between 1990 and 2003 and also closed by the Spanish court. Years later, in 2010, the National Court declared that, like Egin, Egunkaria’s closure had been illegal. In 2012, the European Court of Human Rights condemned Spain for not investigating allegations of torture of Egunkaria editor Martxelo Otamendi.

‘Ideological Successor’ Gara

A few months after Egin’s shutdown, Basque bilingual daily newspaper Gara was born, espousing a Basque nationalist left ideology.

Gara is today considered the “ideological successor” of Egin and, therefore, is being forced to pay the debt that Egin had with Spain’s Social Security – about €4.7 million ($5.2 million). The fact that Egin was closed illegally did not weigh in on the decision to impose debts on Gara contracted by Egin’s forced closure.

In other words, debts created due to the illegal closure of Egin serve as a basis for the continuation of ideological persecution against the Basque nationalist left and its main newspaper, even after the end the armed struggle. This appears to be the continuation of a process of revenge against the resistance of the Basques in giving up their fight for independence.

It is a clear attack on freedom of press and freedom of expression. In Spain, unfortunately, this has become commonplace.

Basque’s Independence Movement

Amid the Catalan crisis, in which Spanish justice will try political prisoners for exercising their political mandates and carrying forward the historical agendas of their parties and the popular yearning reflected in a referendum, Basque’s independence movement seems not to have been forgotten.

Spain’s attempt to pass on the debt created by its own illegal actions reflects its continuation of the war against freedom of expression and the ideology of “everything is ETA,” even with the group not even existing anymore.

If many felt that Spain would have fewer ways of attacking the Basque pro-independence movement after a 2017 case, in which eight young people in the small Basque town of Altsasu were arrested and convicted of terrorism for merely getting involved in a bar fight. Given that shortly after the incident ETA decided to dissolve, the truth is that there is still ample room for censorship and political persecution.

Control and Censorship

Gara’s director Inaki Soto said that the Spanish action is a “hard blow” and that the newspaper now depends on the Basque society to make the payment due, despite their belief that the whole situation is purely absurd. For Soto, this is a case of injustice in which one newspaper has to pay the debts of another based on the fragile theory of “ideological succession of companies.”

Gara is considered Egin’s successor by the mere fact of defending the same ideological positions, although the team, projects, headquarters, and even means of financing are completely different.

Just as in Catalonia, the Spanish government and justice use and abuse of all types of power, be it police or financial, and use intimidation tactics to control, curb or even force to dissolve the movement for the independence of regions subjected to fierce control and censorship.

Gara will face a hard battle for its survival and the maintenance of hundreds of direct and indirect jobs of the third most-read newspaper of the Basque Country and Navarre.

The newspaper hopes it can count on the solidarity of Basque citizens in search of new readers so that it can face the imposed debt. The daily also prepares activities (such as musical concerts) and special releases as a way to increase sales. Gara needs 10,000 new subscribers to continue operating.

In the meantime, Spain does not have the capacity to even pretend to be a European democratic state, carrying countless convictions for human rights violations at the European Court of Human Rights and displaying pathetic episodes of persecution of minorities and their political movements, showing values incompatible with those of the European Union and any modern democratic state.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of The Globe Post.