Lead has poisoned drinking water in Flint, Michigan since April 2014, sparking a national discussion about water contamination, but lack of access to clean drinking water is a far-reaching problem that extends to virtually every corner of the United States.

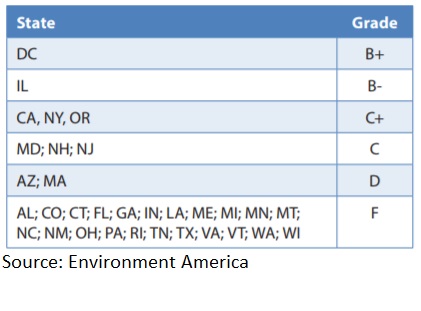

In March, the Environment America Research and Policy Center and U.S. Public Interest Rights Group reported 21 states are currently failing to keep lead out of the water of their schools. States received letter grades from Environment America and were graded on a number of criteria, including transparency, the lead levels which trigger remedial action, whether schools are required to proactively remove lead from water delivery systems, whether testing is required and whether the laws apply to all schools in a given state. Washington D.C. was the highest ranking in the country with a B+.

Senior Attorney for Environment America, John Rumpler told The Globe Post the main reason lead contaminates drinking water is the manufacturing of water delivery systems with lead in them. Examples include water fountains, pipes, and faucets.

Health effects associated with lead include toxicity to every organ system, though neurological effects on children are “of greatest concern” and can cause lifelong damage according to a toxicological profile by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry(ATSDR).

Lead isn’t the only contaminant threatening the quality of drinking water in the U.S. either. According to an analysis by the Environmental Working Group, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) could be contaminating the drinking water of up to 110 million Americans. Not only that, but the Food and Drug Administration has detected the chemicals in food as well. PFAS are associated with a litany of health problems including cancer, decreased fertility, thyroid disease, immune system issues and lower birthweight according to a toxicological profile from the ATSDR.

“Lead comes from older infrastructure and plumbing, but other chemicals like PFAS are used heavily in all products that you can think of,” Director of the Safe Drinking Water Program at the Northeast-Midwest Institute Sri Vedachalam told The Globe Post. “For instance jackets, water repellant shoes, firefighting foam and things like that.”

PFAS contamination of water is linked mainly to facilities where PFAS are produced or used for manufacturing certain products as well as military airfields or oil refineries where the chemicals are used to extinguish fires. In August of 2017, the U.S. Defense Department identified 401 installations in the U.S. with at least one area with known or suspected PFAS contamination. PFAS can also accumulate over time as they are “very persistent” in both the environment and the human body.

Hundreds of industrial manufacturers may be discharging toxic #PFAS, but there are no limits on industrial PFAS discharges and no requirement to disclosure PFAS releases. https://t.co/meuoBnYFaD

— EWG (@ewg) June 11, 2019

“They’re long chain chemicals with an extremely long life,” Beth Hammon, a legislative assistant for U.S. Representative Harley Rouda told The Globe Post. “They’re very mobile in the environment both through soil and water. Something like 98 to 99 percent of all human beings on earth have it in their blood or tissue. They’re forever chemicals.”

While the threat posed by chemicals in drinking water is clear, the path to actionable solutions is far more uncertain. According to Vedachalam, the U.S. regulatory process for such chemicals is largely reactionary, as exemplified by the over 20 years long effort to regulate perchlorates, a chemical used in jet fuel, that may ultimately end with no further regulation. Essentially, chemicals are allowed to be widely used unless they are found to be harmful. Vedachalam contrasted this approach with Europe’s “slightly different principle” of regulating chemicals from the beginning and only allowing the use of chemicals that are not found to be harmful.

“We had lead plumbing up until the ’80s even though we knew about the impacts of lead…in the ’50s and ’60s,” Vedachalam said. “But we allowed lead simply because that’s how we process things. Similarly with PFAS… the evidence is telling us a lot, but the EPA has still not processed that information.”

This is the richest country on Earth and our people don't have clean water.

That's an international disgrace.

Our solution: the WATER Act, which would create more than a million jobs to overhaul our nation's water infrastructure. pic.twitter.com/JvHnTT0RIZ

— Bernie Sanders (@BernieSanders) May 29, 2019

The Environmental Protection Agency released its “Comprehensive Nationwide PFAS Action Plan” in February, but with a long and arduous regulatory process, regulations won’t go into effect until December 2020 at the earliest. Until then, it’s been left to states to pick up the slack.

Rumpler highlighted three major policy goals of Environment America’s effort to “Get the lead out.” The primary goal is to remove water delivery systems made with lead and replacing them with lead-free parts in the long term. In the short term, Rumpler said the best preventative measure would be to install filters certified by the National Sanitation Foundation on every faucet or fountain used for drinking and cooking in schools and preschools.

“We know that we’re not going to be able to remove all of these lead parts right away, so we need to take immediate action,” Rumpler said. “This is a low-cost thing that can be done to dramatically reduce the risk to children. It ought to be done everywhere right now.”

People whose water is polluted with TCE can inhale the chemical during bathing, showering, washing dishes and other everyday activities. https://t.co/bssvHqJBkn

— EWG (@ewg) June 11, 2019

Finally, Rumpler said schools and states should adopt a 1 part per billion(ppb) standard for drinking water at schools, preschools and childcare facilities. The American Academy of Pediatrics also recommended a standard of 1 ppb for schools in a 2016 report.

According to Rumpler, the most important thing the federal government can currently do is provide “substantial” funding to states, communities and local school boards. Rumpler added that funding could also come from state and local governments, but that ultimately, funding would have to come from somewhere in order to ensure safe drinking water for children in the U.S.

“Right now, there are not nearly enough resources for schools to be able to take these steps,” Rumpler said. “One way or another, money is going to have to come forward.”

Captured: How the Fossil Fuel Industry Took Control of the EPA