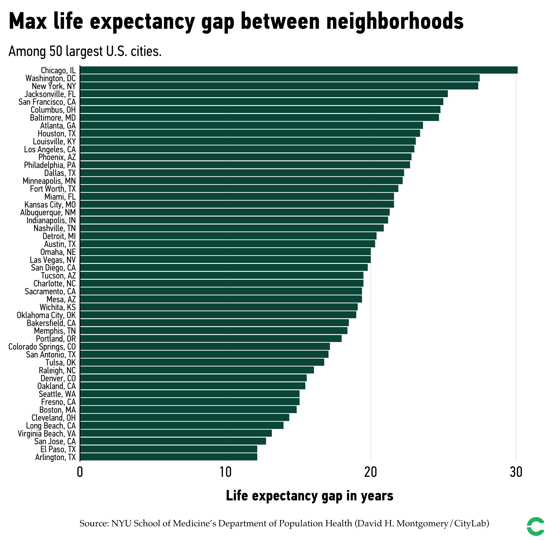

In major cities across the United States, life expectancy can differ between 20 to 30 years depending on what neighborhood you live in, and the gap is widest in cities with extreme racial segregation, a recent study found.

An analysis by the Department of Population Health at New York University’s School of Medicine, using data from the City Health Dashboard, showed that of the 500 cities across the country with over 66,000 residents, life expectancy varied the most in cities that have higher levels of racial segregation.

Chicago had the largest life expectancy gap of 30.1 years among its population, while also being ranked as one of the most segregated cities in the U.S. And in New York, a person living in East Harlem has a life expectancy of 71.2 years, while a few blocks away on the Upper East Side the average life expectancy is 89.9 years. New York is also second on the list of the most segregated cities in America according to the U.S Census Bureau’s 2013-2017 American Community Survey.

“We’ve known for a while that conditions in our neighborhoods can have a profound influence on how long and how well we live. But we were surprised to see just how large the gap in life expectancy can be between neighborhoods, and how strong the link was between life expectancy and segregation, across all different kinds and sizes of cities,” says Benjamin Spoer, from the Department of Population Health at NYU Langone Health.

Why Is Racial Segregation Still An Issue In 2019?

From Jim Crow to redlining to discriminatory mortgage lending policies, segregation has always been a part of the fabric of America. But as the country advances and economic opportunities increase neighborhoods with majority minorities still feel the impact of segregation and the lack of help to combat it.

The type of racial segregation we see today in metropolitan areas became more prevalent in the 1960s due to “white flight” which was when white families began migrating to the suburbs. One of the reasons for this was the fear that if minorities started moving into their inner-city neighborhoods, the housing prices would decrease due to discrimination in the real estate industry.

Further, white families had the largest share of wealth during this time (as they do today) so when they left inner-city neighborhoods they took much of the tax base with them, said Mark Treskon, a senior research associate at the Urban Institute.

Local taxes make up a large portion of funding for education and community infrastructure such as libraries and parks. When the white middle to upper-class tax-base moved to the suburbs, local governments were only able to pay for the bare necessities and many important aspects of community life fell behind.

Matthew Hall, an associate professor of policy analysis and management at Cornell University, accredited racial segregation as one of the main contributors to various problems in inner-city, low-income neighborhoods.

“Extensive research has shown that racial segregation undercuts job opportunities, stalls educational progress, and concentrates poverty, which heightens exposure to crime, toxic pollutants, and other social ills,” he said.

It is not only economic factors which are affected by racially segregated communities. Hall also pointed out that racial segregation limits contact between racial groups and has a direct impact on friendships, romantic partners and other facets of our social networks.

Although the analysis by NYU connects life expectancy with racial segregation throughout the U.S., Treskon cautioned against looking at racial residential segregation as a uniform problem because it varies greatly between cities.

The map for racial segregation differs throughout America because many policies are administered at a state and local level. Treskon said he believes for there to be any real change in racial residential segregation, and in turn life expectancy rates, the federal government would have to get involved and create a nationwide policy.

“The story is playing out differently in different places across the country, is something to really keep in mind,” said Treskon. “Anything to happen at the Federal level would be great, I don’t see anything happening right now, but at the local and regional level is where there might be some action depending on certain places actually looking at and thinking about this more systematically.”

Solutions to combat racial residential segregation have been tested throughout the country with mixed-income housing being one of the most popular. Hall said these types of housing projects could help reduce racial segregation over time.

“Segregation is stubborn and slow to change, but recent research indicates that expanding housing access, particularly affordable and mixed-income types, tends to reduce segregation in the aggregate,” said Hall.