India’s financial capital, Mumbai, generates 11,000 tonnes of waste daily. In the absence of a proper waste segregation and recycling system, the city’s only saving grace are thousands of unauthorized recyclers, who run their operations in Mumbai’s infamous Dharavi slums.

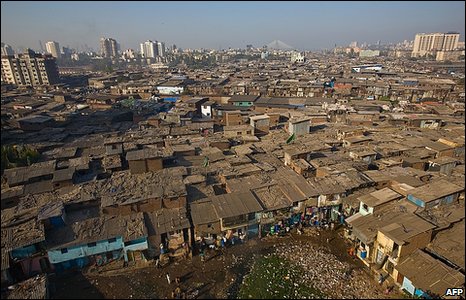

Dharavi, the biggest slum of Asia, is an eyesore to the neat and continually rising skyline of Mumbai. A labyrinth of thousands of small workshops and homes, Dharavi is located right in the heart of the maximum city, making it one of the most expensive pieces of land in India, housing the poorest of the poor. It is hard to believe that this mesh of shanties and narrow lanes, littered with garbage and flooded with sewage water, is what prevents the financial capital of India from choking in its own waste.

Spread across 520 acres of land, Dharavi is the center of recycling of thousands of tonnes of waste that Mumbai generates every day. More than 5,000 single-room recycling units work relentlessly to skim through unsegregated and monumental quantities of waste to cull out metals, plastic, paper, and glass.

Laxmi Kamble, a single mother and a third-generation Dharavi resident said that recycling has been a business in the slum since independence.

Making of Dharavi

Dharavi came into existence in 1882 during the British colonial rule in India. An outbreak of bubonic plague in Mumbai prompted the British government to transfer some of the polluting industries to a piece of land that later came to be known as Dharavi. With the advent of mechanized technology, labor-intensive industries died out and Dharavi became the abode of migrant-waves that swarm the city every month.

Recycling eventually emerged as a profitable business. Director of Acorn Foundation (India), Vinod Shetty, said that it is hard to make profits for organized recycling businesses in India due to the lack of a system to segregate waste at the source and keep it segregated during the transit. Garbage trucks managed by Brihanmumbai Municipal Commission do not have provisions to carry segregated waste which is simply toppled inside the trucks and dumped in landfills on the outskirts of the city.

India’s largest and the oldest dumping ground, Deonar, is located in the eastern suburb of Mumbai. Deonar landfill occupies an area big enough to encapsulate more than 240 football fields. Set up in 1927, Deonar landfill now has mounds of trash that have attained a height equivalent to a nine-story building. In 2016, a fire broke out at the landfill. The dump continued to be on fire for four days, forcing 70 schools to dismiss classes.

A high disposable income and lack of awareness and concern for the environment among urban masses has led to a 105 percent rise in waste generation in Mumbai between 1999 and 2016. Recycling units in Dharavi play a huge role in intercepting recyclable items from getting dumped into a landfill and adding to Mumbai’s mounting waste crisis.

Supply Chain of Recycling

Through the decades, these unorganized recyclers have developed an organized and robust supply and demand network that contributes to Dharavi’s total annual turnover of US$1 billion. The smallest unit of this supply chain are ragpickers who skim through trash bins and landfills to pick out recyclable articles. A typical day for Balu, a ragpicker, starts with a glass of strong black tea and a snack. For the next 12 hours, he will be meticulously fishing out recyclable items from public trash bins. “You won’t believe the kind of things that I find in the garbage. Once I found a fully functional foot massager,” he said. On other days Balu makes less than $3 a day, which barely covers his food expense.

Sorting recyclable items from dumps exposes ragpickers such as Balu to a variety of health hazards. At 17, Balu complains of shortness of breath, but he cannot afford to consult a doctor or buy medicine. “It is a skill that you acquire at the cost of your health. Once I opened a bottle of liquid and spilled some of it on my hand. I think it was acid as it burnt the skin on my hand,” he said while showing a patch of burnt skin on his hand. “I don’t have a choice, rag-picking is the only way I can make a living.”

Recyclers also source material from Kabadiwalas. For decades, Indians have been selling recyclable household waste to these door-to-door collectors. The Kabadiwalas make rounds of residential areas while pushing their hand wagons, announcing their presence. People call them to their homes to sell paper, plastic, glass, and electronics. Many haggle to get the best price out of a kabadiwala for their discarded items. The kabadiwalas sell their purchase to recyclers in Dharavi for a paltry profit of 5 to 10 percent. The most organized of all these suppliers are scrap agents who buy large quantities of reusable waste auctioned by companies and then sell it for a profit.

Hours of Labor

Shirish Jani, a second-generation entrepreneur, is very proud of his family business which was started by his father in 1962. His 250 square feet recycling unit is packed to the rafters with cardboard, paper, and plastic barrels.

“We often buy plastic and cardboard through a scrap agent who has ties with the pharma and chemical companies. The purchased scrap is then transported to our recycling unit in Dharavi. After washing and processing we generate a profit of 10 percent,” said Jani.

Repackaging units with a small demand serve as clients for recyclers such as Jani.

Dharavi’s thirteen compounds have mounds of segregated colored plastic. Segregated plastic is ground and the granules are sold to packaging companies. However, the process of dismantling and sorting needs hours of labor.

Shadab Chaudhary left behind his wife and two daughters in his village in North India to come to Mumbai for work. The lack of blue-collar jobs in rural areas stimulates waves of labor migration to Mumbai. Shadab works 12 hours every day and sleeps on the pavement to save enough money to send home. “I get paid Rs.10,000 ($144) a month, this is the best you can get here,” he said.

Second Life

Metal extraction from e-waste to the refurbishing of second-hand home appliances, there is nothing that cannot be used or reused in Dharavi. At 18, Sandeep Soni is the proud owner of a second-hand home appliance shop that supports his family of six. A customer can buy a functioning washing machine at one-third of its original price from his shop. “We even give a guarantee of three months,” he said. On days with slow business, his staff consisting of three teenage boys sit in the dark backroom to extract copper from discarded electronics which fetches him about $5 per kilogram.

E-waste recycling in Dharavi is not as popular as plastic, paper, and glass, owing to the hazardous nature of the extraction techniques. The metal extractors at Dharavi employ two to three workers at a time to extract profitable quantity of metals. Workers sit in an assembly line fashion with each taking a different set of responsibility during the extraction process. Javed* has been making his living through metal extraction from discarded e-waste for over a decade now. “I extract metals after taking apart electronics. There is a huge market for metal extraction from PCBs but I lack knowledge and equipment,” he said.

Governmental Guidelines

In 2016, the Government of India introduced Extended Producer Responsibility to ensure that the industries associated with plastic and electronics take the onus of recycling end-of-cycle products by establishing collection systems. Since 2016, the Central Pollution Control Board has been cracked down on some of the major electronics companies in India for not complying with the norms. According to the same set of rules, the dismantling of e-waste is only allowed to be done by authorized recyclers in workshops equipped to carry out the processes with compliance to the central government’s 2016 guidelines for e-waste management.

For Dharavi’s e-waste recyclers such as Javed, it is impossible to execute environmentally safe dismantling of e-waste, and there is no way for him to acquire an authorization to conduct his business legally.

“We have a hand-to-mouth existence. We have neither time nor capital to invest in compliance. My business may not be legal but it is essential. E-waste recyclers in an unorganized sector not just earn a living through recycling, but also process tonnes of e-waste, which is beyond the capacity and means of recyclers in the organized sector,” he said.

Acorn Foundation (India) Director Shetty works closely with recyclers in Dharavi to provide them with legal advice and solicit licenses and permits on their behalf. He calls the situation of Dharavi recyclers an epitome of Catch-22. “Excluding the unorganized sector from the recycling ecosystem is a mistake. Organized recycling units do not have the benefit of cheap migrant labor and a seamless supply network,” he said. “Only people who are destitute and desperate for work will put such hard labor to make a meager living.”

For Shadab and Javed, the pros and cons of their profession hold little importance. “I don’t understand legalities associated with my business. I try my best to keep my workers safe and only extract metals that can be easily extracted,” said Javed.

For Shadab, the illegal status of his workplace makes no difference. “What would you choose between supporting your family now and developing a new set of skills in an attempt to find some other kind of legal job,” Shadab said.

Environmentalists, organized recyclers, electronics, and plastic product manufacturers and the government are yet to devise a sturdy waste management system in India. Meanwhile, thousands of recyclers and labors in Dharavi continue to process the waste generated by the millions of inhabitants of Mumbai.

*Name of the metal extractor Javed has been changed to protect his identity.

This article won The Globe Post’s 2019 writing contest.