The homeless are living in “our best highways, our best streets, our best entrances to buildings.” This is what President Donald Trump said, disparagingly, during his last visit to California, where almost half of all unsheltered homeless people in the country live. That’s 47 percent, nearly four times as high as California’s share of the overall U.S. population.

A report published last month by the White House, “the State of Homelessness in America,” outlines how serious and extensive the issue homelessness continues to be in the U.S.

But when did homelessness become a major problem and whose fault is it? While different administrations tend to blame each other for having failed past policies, homelessness has been a significant national issue for well over a century: the emerging urban cities hosted homeless people already in the 1870s. Then the Great Depression of the 1930’s left millions of people without a house, and in the ’80s, the numbers increased as housing and social service cuts increased.

According to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Annual Homeless Assessment Report, on a given night in 2018, more than half a million people were experiencing homelessness in the United States.

Today a person is defined as homeless by the Department of Housing and Urban Development if he or she “lacks a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence.”

There’s also a distinction between sheltered and unsheltered homeless: the first are those who stay in shelters or in other residential programs within a local homeless assistance network, while the second are those who decide for one reason to another to live in the streets or in abandoned buildings, refusing assistance and a bed to sleep in.

From the West to the East Coast, the numbers of unsheltered and sheltered homeless people vary a lot, mostly depending on the housing market and the often sky-high prices for rents in America’s big cities.

(Un)affordable Housing

Last June, President Trump signed an executive order that will seek to remove regulatory barriers in the housing market, claiming that it would reduce the price of homes and reduce homelessness.

But what it is happening in the major cities seems to be the exact opposite, especially because the cost of living is increasing rather than decreasing, In 2017, for example, approximately 37 million households were spending more than 30 percent of their income on housing.

In Europe in 2018, the average monthly rental cost for apartments did not go over $2,800 U.S. In the American cities of San Francisco, New York and San Jose, the average price for one room bedroom goes between $2,500 and $3,500.

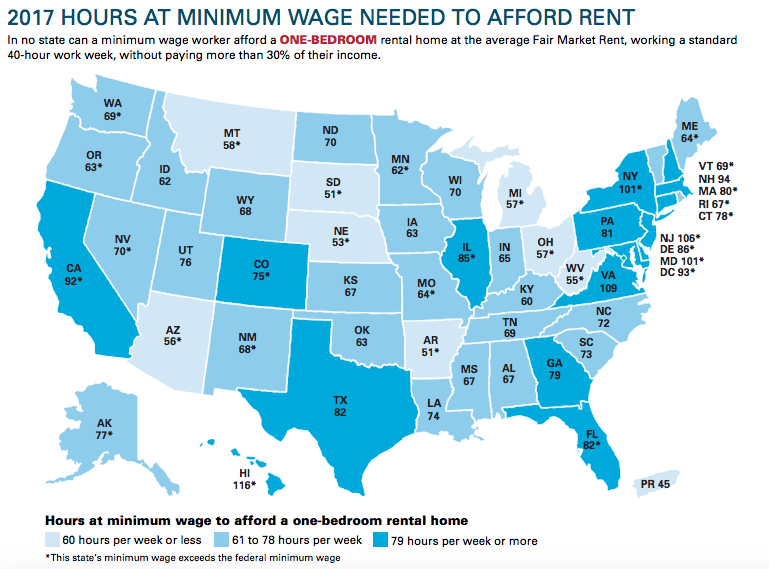

In many places, the wage required to rent an apartment in 2017 was many times higher than the federal minimum wage – $7.25 – or the minimum wages of any state.

In fact, according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, there is nowhere in American where a full-time minimum wage employee could afford a one-bedroom apartment without spending more than 30 percent of their income on housing.

The coalition found that a full-time worker earning the minimum wage would need to work on average 94.5 hours per week for all 52 weeks of the year to afford a one-bedroom rental home.

Amidst wages that have not kept pace with the cost of apartments, we are seeing every year increasing numbers of people who simply can’t afford to pay for the rents or who are being evicted.

Compared to a national rate of 17 homeless people per 10,000, the cities with the highest rates of overall homelessness in 2018 were Washington D.C., followed by Boston and New York: respectively there were 103, 102 and 101 homeless per 10,000 citizens. For cities, the highest rates of unsheltered homelessness were all in California: San Francisco, 59.8, Los Angeles, 40.4 and Santa Rosa with 38.5.

Destigmatizing Homelessness

If the government is still trying to find solutions to homelessness, as Trump suggests, there are many organizations dedicated to helping homeless people, not only to give them a bed to sleep in, but also a chance for a better future.

LA Mission in Los Angeles and Coalition for the Homeless in Washington, D.C. are just two of them, the first one founded in 1936 as a non-profit, privately supported organization, and the second, originally conceived of in 1979 as an advocacy organization, was then incorporated as a non-profit organization and is funded largely by the District government. They both provide shelter services but have also incorporated programs on different issues, from mental illness to education.

The main obstacle the organization sees to reducing homelessness is the lack of affordable housing.

“That really is a national issue … the lack of affordable housing and resources to get people in to affordable housing,” Coalition for the Homeless’ Executive Director Michael Ferrell told The Globe Post.

Los Angeles Mission President Herb Smith believes there’s also a big image issue that needs to be clearly understood by ordinary people and officials like Trump, who often depict homeless people negatively, using words like “filthy” and “dirty.”

“The reality is that … it might have been your next door neighbor who, because of a medical emergency, declared bankruptcy, ended up unable to pay the rent and was evicted and now needs a place to live. So many people are just one paycheck ahead of homelessness,” Smith concluded.