In early August, days before representatives from the Venezuelan government and opposition were scheduled to reconvene for talks in Barbados, the U.S. announced it would be imposing a near-total economic embargo on the country.

In response, Venezuelan President Nicholas Maduro canceled the talks, scuttling hopes that the two sides could make progress towards a negotiated settlement to the country’s ongoing political crisis.

For analysts following the stalemate, the timing of the new American sanctions was suspect.

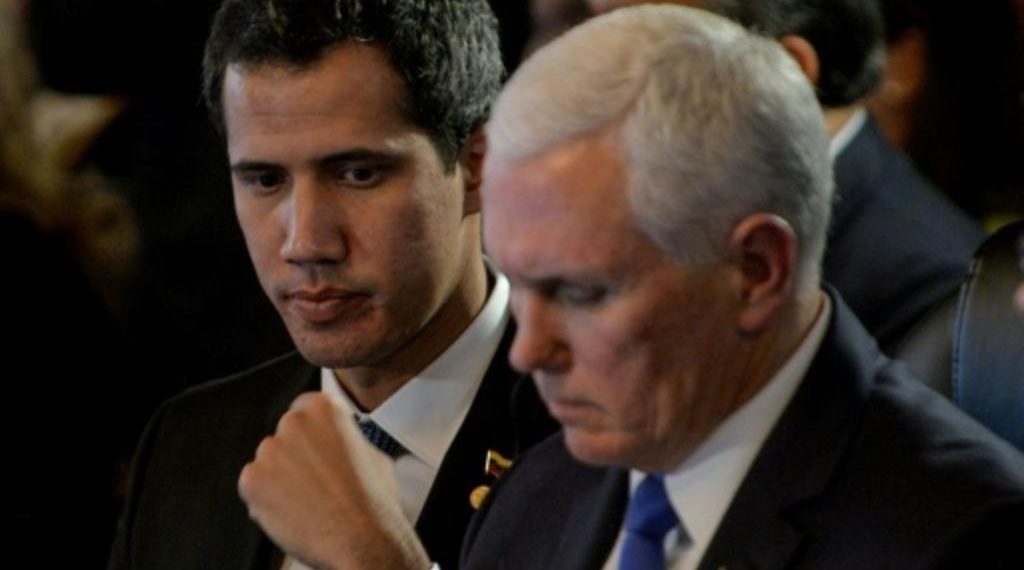

In January, U.S.-backed opposition leader Juan Guaido declared himself interim president and demanded that Maduro step down immediately. In the ensuing months, he even led several unsuccessful attempts to topple the government.

But during the talks in Barbados, Guaido and his allies softened their stance, proposing the establishment of a transition government in which both sides would be represented before new elections would take place.

The proposal, however, would go unanswered, as the announcement of the new sanctions – made by former National Security Advisor John Bolton in Lima on August 5 – led to the break down of the talks.

“The U.S. knew perfectly well that there was a proposal on the table and that the ball was in the government’s court,” Phillip Gunson, a Caracas-based analyst with the Crisis Group, told The Globe Post. “It was either very clumsy or it was deliberate.”

According to Gunson, the opposition negotiators were “taken completely by surprise” by the sanctions. And while Guaido and his allies in many ways remain dependent on American support, the Barbados episode highlights the extent to which the Trump administration and the various elements of the opposition have competing and divergent interests at play in Venezuela’s political drama.

‘Awkward Ally’

There’s no certainty that Maduro would have accepted the terms of the offer made by the opposition in Barbados, but the undermining of the diplomatic process by the U.S. – intentional or not – has made the situation in Venezuela bleaker, both for ordinary people and for the opposition.

“What was left is a country deeper in misery because of huge sanctions and an opposition that has largely lost a significant amount of credibility among internal factions in Venezuela, especially popular sectors,” Alejandro Velasco, a historian of modern Latin America at New York University and the executive editor of NACLA Report on the Americas, told The Globe Post.

U.S. sanctions, imposed first by Barack Obama’s administration in 2015 and then escalated significantly by Donald Trump beginning in 2017, have taken a serious toll on Venezuelans. With the economy already suffering from severe hyperinflation, the sanctions have prevented a possible recovery and have made it difficult for the government to import medicine and equipment to sustain civilian infrastructure, like water and electric systems.

The Washington-based Center for Economic and Policy Research estimates that American sanctions have caused the deaths of about 40,000 people since 2017, as Venezuelans with serious medical conditions have been forced to go with little or no treatment.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the United States is hugely unpopular among some sectors in Venezuela, particularly among “Chavistas” – the mostly lower-class supporters of former president Hugo Chavez and his United Socialist Party (PSUV), of which Maduro is the heir.

“They don’t care,” Carolina Subero, a mother who is struggling to get medication for her epileptic daughter, said of the U.S., speaking to the German publication DW earlier this month.

“They think they are hurting President Maduro, and they’re really hurting the people. If they really wanted something good for Venezuela, they would not be doing what they are doing right now.”

Thus, Washington is an increasingly “awkward,” “uncomfortable” ally for the opposition, Gunson said.

“The fact that the opposition is so dependent on the U.S. makes it’s very easy for the government to turn around and say, ‘well, these guys just represent the U.S. They’re traitors. They’re trying to overthrow the government because the U.S. wants our oil,” he said.

“It’s hugely over-simplistic, but it is something that has a certain resonance with the Venezuelan electorate.”

Divergent Interests

The opposition’s dependence on the U.S. stems from the fact that it wields little power within Venezuela, even with its control over the legislative branch. Despite his dwindling popularity, Maduro maintains firm control over the supreme court and the military and has driven many opposition figures into exile or prison. Without outside pressure, Maduro would have little incentive to even negotiate with the opposition or allow Guaido to operate freely.

Further, Guaido’s bloc also benefits from financial support from the U.S. government. On Tuesday, the U.S. Agency for International Development pledged an additional $98 million in aid for the opposition. But the aid also comes with its costs.

“I think the opposition lost a lot of credibility by being so openly aligned with the United States in this effort to get Maduro out,” Daniel Hellinger, a Venezuela expert and professor emeritus at Webster University, told The Globe Post.

Making matters more difficult for Guaido is the Trump administration’s refusal to back down from its hardline anti-Maduro stance. The U.S., along with about 50 allied countries, recognizes Guaido as the “legitimate” leader of Venezuela and maintains that Maduro is a “usurper,” arguing his 2018 reelection victory was illegitimate because high-profile opposition figures were barred from running.

Even with the opposition’s efforts to find a negotiated solution, the Trump administration has little interest in compromise, as its hawkish posture plays well among many in the strategically important Latino community in Florida going into the 2020 election. The strategy is evidenced by the outsized role played Florida Republican Senator Marco Rubio in driving Washington’s aggressive Venezuela policy.

“Trump in particular, and maybe Senator Rubio and others, require Maduro to go because they want to declare victory,” Gunson said. “And if he doesn’t go, their political interest is better served by rattling sabers and being very belligerent than it is by seeking a compromise.”

Fracturing Opposition?

As things in Venezuela continue to get worse, Guaido has seen a “huge drop” in popularity following the failure of the Barbados talks, Velasco said, citing recent polling he regards as reliable.

Before his recent decline in popularity, Guiado was widely recognized as the most popular politician in Venezuela and remains much more popular than Maduro. His control over the various elements of the mainstream opposition under the umbrella coalition the Democratic Unity Roundtable (MUD), however, is somewhat tenuous.

There is little underlying ideological consensus holding together the MUD, which was formed in 2008 as a pragmatic means to challenge Chavez electorally.

Guiado’s position as the de facto leader of the coalition is also somewhat controversial among the opposition. His attempted power grab in January rested on his status as the leader of the National Assembly, the only “legitimate” democratically elected branch of the government, according to the opposition and most analysts. But his leadership was only temporary, coming about as part of an agreement among the major parties in the MUD to periodically rotate the leadership.

With Leopoldo Lopez the leader of Guaido’s party, Popular Will, in hiding in the Spanish embassy, Guaido stepped in as head of the assembly on January 5. Though he is well-respected by many in the assembly, some officials in more moderate parties were “a little nervous” about what the more radical Guaido would do with the position, Gunson said.

Just 18 days later, he declared himself interim president at a rally in Caracas, setting off the political crisis. All of the experts interviewed by The Globe Post agreed that the move was planned in close coordination with Washington and that it was part of a broader international attempt to topple Maduro. While it’s unclear whether the leaders of other parties supported the move at the time, Gunson said the strategy was devised “largely behind the backs of other people in the opposition.”

Though the MUD has shown a mostly united front publicly since Guaido’s move, recent events seem to show “a small crack in the opposition that could easily widen,” Hellinger said.

Perhaps trying to take advantage of the moment, a smaller, moderate sector of the opposition broke with the MUD and struck a separate, limited agreement with Maudro in September. This moderate sector includes four parties whose leaders backed the candidacy of Henri Falcon in the 2018 presidential election, which was boycotted by the rest of the opposition.

Only two of the parties – Cambiemos Movimiento Ciudadano and Avanzada Progresista – hold seats in Venezuela’s National Assembly, comprising just six seats collectively in the 167-member body.

As part of the deal, Maduro has agreed to send Chavista representatives back to the National Assembly, free an unspecified number of political prisoners, and make modest improvements to election oversight.

Though its viewed as a potentially promising development, the results of the agreement have thus far been “pretty thin,” Gunson said, as only one political prisoner has been freed. Further, the vast majority of opposition representatives have not returned to the assembly, which cannot pass any legislation anyway because the supreme court has declared the body in contempt.

Nonetheless, the moderates “clearly believe that their strength will grow if they’re able to show that they have made some headway … even if it’s a very slow, incremental process,” Gunson said.

But there are also radical, fringe elements of the opposition that have broken in the opposite direction. Increasingly, Gunson said he has seen a growing body of far-right opinion in the opposition, though it remains a small minority. On social media, some opposition supporters have made “bloodcurdling proposals” such as calling for the U.S. to bomb the country, the banning of Chavismo, the killing or imprisonment of government figures, and even the rise of a Pinochet-like figure – a reference to Chile’s former far-right dictator.

These more “resentful, vengeful” Maduro opponents have largely coalesced around a new party, Soy Venezuela, formed in September 2018 by a group of exiled and radical opposition figures. It’s most prominent figure is María Corina Machado, who has not called for banning Chavismo or the rise of a dictator but does reject negotiations and supports a foreign military intervention to overthrow Maduro.

While Soy Venezuela remains on the fringe, Gunson warned the ultra-radical elements could become increasingly emboldened the longer the crisis goes unresolved. And while the broader fractures in the opposition have been minimal so far, Hellinger expects it will be increasingly difficult to hold together a common front going forward.

“The failure of this, for lack of a better term, coup attempt, really leaves the opposition in disarray,” he said.

‘The House is Burning Down’

For ordinary Venezualans, particularly the poor, the current situation represents the worst of all worlds.

“People in Venezuela continue to suffer both from a completely inept, corrupt government and now increasingly from the effects of sanctions, which are brutal,” Velasco said.

While more affluent sectors, which make up much of the opposition’s base of support, have been able to weather the storm to some extent, the poor have borne the brunt of the economic crisis.

Amid the suffering, genuine support for Maduro in poor communities, such as the traditional Chavista stronghold of Western Caracas, is rare. But dissatisfaction with the government does not necessarily translate into support for the opposition. During attempts to reach out to these communities, Guaido has been met with violence.

In addition to distrust of the United States, many poor Venezuelans fear that a potential Guaido government would threaten the subsidies and social programs that they rely on.

While opposition leaders have tried to reassure popular sectors, they’ve also been clear they would seek to lure foreign capital into the country if put in power.

That would “by necessity … mean things like privatizing sectors of the oil company. It would mean curtailing even the meager amounts of subsidies that continue to be received,” Velasco said.

But a continuation of the status quo is also a daunting proposition for poor Venezuelans, millions of whom have already fled the country in desperation.

An end to the crisis will require more political will from all sides, including the United States, though experts agree it’s inconceivable that the Trump administration would cede any ground before the 2020 election.

“When it comes down to it, what both sides are doing is they’re playing this power game,” Hellinger said. “Meanwhile, the house is burning down all around them.”

Nachiketh Mamani contributed reporting to this article.

More on the Subject

‘Our Hemisphere:’ Understanding the US Campaign Against Socialism in Latin America