Bolivia has entered a period of deep uncertainty following a coup that ousted leftist President Evo Morales and other top government officials on Sunday.

The overthrow of Morales came three weeks after he won re-election in polls that were marred by disputed, unsubstantiated allegations of fraud.

Nonetheless, the fraud allegations sparked weeks of violence, terror, and unrest, culminating in the president resigning under pressure from the military.

With Morales now in Mexico, the situation in Bolivia remains highly volatile, as waves of predominately-indigenous Morales supporters have taken to the streets to demonstrate against the coup, at times clashing with the military.

On Tuesday, The Globe Post‘s Bryan Bowman spoke with Alex Main, a Latin America expert and the director of international policy at the Center for Economic and Policy Research, about what happened in Bolivia and what the country might look like when the dust settles.

The interview has been lightly edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Bowman: What is the situation like in Bolivia now? How volatile is it and do we have any sense of who is currently in charge of the country and who might ultimately replace Morales?

Main: At the moment, I would say that the military’s really in charge. There’s no indication that there’s any politician that has really taken control. But you do have politicians that are angling to take control. You have one far-right opposition leader, Luis Camacho, who has been out there the most and went as far as getting into and occupying the presidential palace.

And then you have Jeanine Anez, who is the leader of the opposition in the Senate and who is arguing that she is next in the line of succession because everyone else has resigned – not really voluntarily, under threat. The various options under the Constitutional succession are now all gone. And there’s no agreement between the opposition forces.

Carlos Mesa, who was the runner up in the elections from the opposition, has almost disappeared from the whole scene. So it’s really some of the more radical members of the opposition that seem to be exercising more influence.

So we can just say that there’s a vacuum of power right now and that the military is kind of maintaining order. In fact, they deployed in the streets of Bolivia against the orders of the defense minister from Morales’ cabinet, who resigned this morning. And they’ve been deploying jointly with the police forces, which is actually what the opposition has been asking them to do, which sort of further confirms the military coup nature of what’s going on.

Bowman: Going back to the October 20 election, can you explain the controversy that arose with the vote count. I understand that CEPR published a statistical analysis of the results and that your colleague Mark Weisbrot has been adamant that much of the major media got the story wrong. How do your organization’s findings differ from the prevailing narrative around the election?

Main: One thing that a lot of the media outlets very certifiably have gotten wrong is that they’re confusing the quick count with the official count. The quick count is the unofficial counting system that provides the basis for preliminary results on the day of the election.

So you will read in a lot of places that the vote count was suddenly interrupted for 24 hours and then went back online. Well, that’s not correct. That was the quick vote count and not the official vote count, which unfolded, as far as we can see, without interruption, with sort of constant updates every few minutes.

But it was much slower than the quick count, obviously. In fact, it took over four days to get final results from the official results. And so many media are getting that wrong. And it’s a bit annoying because we and others have been pointing this out. And there have been corrections here and there. But for the most part, the media is not correcting and continuing to repeat this.

And it’s the Organization of American States that has sort of driven this narrative that there was something wrong with the vote counting. They came out with a communique after the quick count had been interrupted – and there are a number of possible reasons for why that happened.

They had around 83 percent of the results that had come in through the quick count, and contrary to past elections in which Evo Morales participated, it was a little bit more of a nail biter in the sense it wasn’t clear from the preliminary results whether he was going to win in the first round or whether they would have to go to a second round.

When they released the preliminary results based on 83 percent, it showed that he didn’t have enough. He didn’t have more than a 10 point margin against the runner up. The only way to win in the first round is either to have 50 percent or at least 40 percent and a 10 point margin against the runner up.

At that point, as they’ve done in previous elections, they stopped updating the quick count. There was a lot of pressure from the OAS and the opposition to get the quick count back online. The government eventually did after about 24 hours, and you saw the margin in favor of Morales rise progressively and he was surpassing the 10-point margin.

And so that’s when the opposition cried foul. But then the OAS also came out with a statement, both denouncing the interruption of the electronic vote count and also saying that there had been a drastic change in the trend of the results as they were coming in and that that change was very surprising and difficult to explain.

The latest OAS “audit”, repeats a major falsehood from their previous reports, pretending that there was an “unusual” jump in Evo’s vote margin towards the end of the quick count. But the change was in fact gradual, as later-reporting areas were more pro-Evo than earlier ones: pic.twitter.com/oFiUFFAl5H

— Mark Weisbrot (@MarkWeisbrot) November 10, 2019

So they cast doubt on the validity of those results. They didn’t have any evidence except for, according to them, this drastic change in the voting trends.

So it was actually quite simple for us – I mean, we did various statistical analyses of the results, but it was actually quite simple to see how that statement was misleading in that there was not a drastic change. There was no drastic change after the 83 percent had been reached and the progression in favor of Morales was unsurprising.

In fact, it was quite predictable because the results coming in were coming in from more rural, poorer areas that traditionally vote a lot more for Morales’ Movement Toward Socialism (MAS) Party. Both the quick count results and the official results reflected this. And his margin grew not drastically, but progressively in his favor. And the final official results showed Morales reached a 10.5 percent margin, which means he won the election.

But of course, the OAS cast doubt on this and that was used very much by the opposition to legitimize their protest.

Bowman: The CEPR analysis concluded that the OAS statement was “a serious breach of the public trust” and was “dangerous in the context of the sharp political polarization and post-election political violence that has taken place in Bolivia.” And unfortunately, we saw that after the publication of that report, violence and unrest escalated quite dramatically. Could you give us a sense of the events that ultimately lead up to the coup and Morales’ resignation?

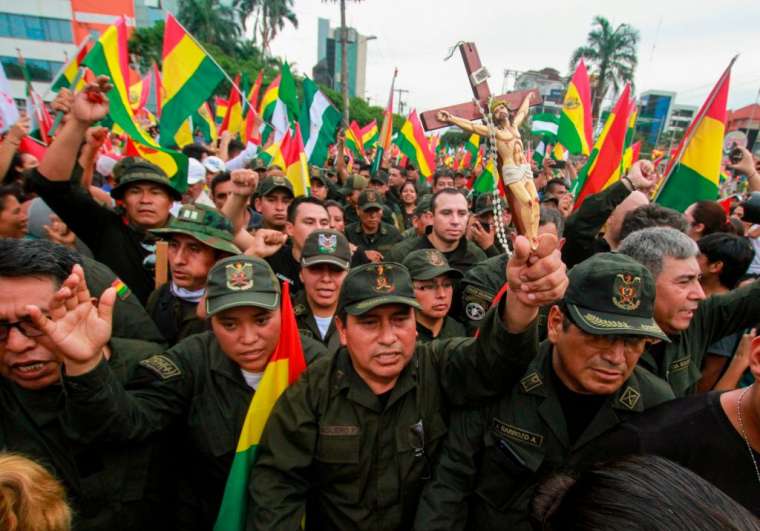

Main: So the election results were immediately contested and the protests grew more violent. The protests were happening in urban areas. There was no sign of protest outside of that. In terms of the socio-economics here, they were more middle and upper-middle class and generally whiter, less indigenous.

Indigenous areas were not protesting. I mean, now they’re protesting, but against the coup.

But the crucial thing that happened at the end of last week was that you had various police forces from different cities “refuse to repress the people.” But what that meant in practice was that you had protesters, some of whom were very violent and were attacking leaders from the MAS and people that they associated with the MAS. And those individuals were not being protected by the police. So that created a very dangerous situation.

The police mutinies spread progressively until the police in La Paz, the capital and largest city in Bolivia, also decided to mutiny. And then on Saturday, the commander of the armed forces announced that they would not intervene against the police mutinies. Basically, at that point it was pretty clear that the armed forces were essentially not supporting the government.

Protesters kidnapped the mayor of a small town in central Bolivia, forcibly cut her hair, drenched her with red paint, made her sign an improvised resignation letter, then marched her through the streets barefoot, witnesses said https://t.co/uEZcXCGdx5

— The New York Times (@nytimes) November 8, 2019

In terms of the succession of events, one of the things Morales did to try to appease the opposition was that he agreed for the OAS to carry out an audit of the electoral process and for the results to be binding, which was pretty unprecedented.

The preliminary results of that audit came out Sunday morning, and they said there were all kinds of irregularities. We’re looking at that audit at the moment, we’ve already found some problems and we’re gonna be publishing something on that, but I don’t have a real analysis to share with you at this point. But it was very vague, which is part of the problem.

But Morales agreed to the OAS recommendation that there be new elections and a new election authority. But protests were continuing and protesters were calling for Morales to resign. And a military commander came out and had a press conference and urged him to resign.

So Morales, accompanied by some masked members of the armed forces, held a press conference with the vice president in which they both denounced the coup taking place and their resignation.

And then in short order after that, you had the resignation of the rest of the Constitutional line of succession, which were all MAS leaders. They said their families were under threat and that they were basically being coerced. Some of their homes had already been attacked. Morales’ home was ransacked.

Morales went into hiding briefly and the Mexican government offered him asylum. He accepted and the Mexican government sent a military plane to fetch him. But there were further complications because neighboring countries, in quite an outrageous way, denied the Mexican airplane the use of their airspace.

Peru had initially granted them access to the airspace, but then they had to sort of turn around because Peru then denied them airspace. Ecuador denied them airspace. Colombia denied them airspace. And so it was looking very, very tricky. Eventually, they managed to get through.

The speculation is that you had, you know, somebody in the White House that was calling these countries and saying, ‘no, you will not allow Evo Morales through your country.’ But we don’t know that, obviously.

Bowman: On that note, there’s been a lot of speculation in the wake of the coup that the United States was involved in some way. Marco Rubio, the Republican Senator from Florida, has been vocal in celebrating Morales’ downfall, and the White House has issued a statement in support of his ouster. What is Washington’s relation to the OAS and do you believe that the U.S. played any role in what ultimately transpired?

Main: No, I am convinced that the U.S. played a big role in what transpired. At the very least, they confirmed they supported the OAS when the OAS made some dubious announcements and recommendations. They were the first to sort of stand behind that.

In terms of the relationship, there are two aspects to the OAS. You have the bureaucracy, and then you have the multilateral side of it, which is represented by the permanent council, where all the member countries participate. And in both cases, I would say you have a very, very strong bias against a government like that of Evo Morales’.

In the case of the bureaucracy and in particular the political appointments within that bureaucracy, you have, for one thing, the majority of the funding, 60 percent, which comes from the U.S. government. So that sustains the institution and you have people who are very allied to members of the Trump administration and people close to the Trump administration like Senator Marco Rubio.

So that’s reflected in the statement and in general from the opinions coming from the secretary-general, Luis Almagro, who has been someone who has campaigned very actively against various left governments.

Sometimes that’s been with legitimate foundations, focusing on human rights violations, but while turning a complete blind eye to any similar issues or issues that are arguably no more flagrant in countries with right-wing governments.

In terms of the OAS electoral mission in Bolivia, the guy in charge of that was a former senior official of a right-wing Costa Rican government and known to be no friend of progressive governments in the region. So, that suggests that there is kind of a built-in bias there.

In terms of the multilateral side, contrary to what was the case just a few years ago, the majority of the countries and in particular the big countries and those that pay the most dues to the OAS are in the hands of right-wing governments, in some case, far-right governments, which is the case I would say today of Brazil and of Colombia. And they’ve been on kind of an active regional campaign to counter the influence, if not undermine the leadership, of what remains of the more left-leaning governments in the region.

Bowman: With Morales now officially gone, what do you think will be his legacy? As the first indigenous president, what did he accomplish in Bolivia? And who were the primary beneficiaries of his policies and conversely, who were his main opponents?

Main: So Morales was in power for 14 years. I wouldn’t write him off completely. He resigned, but he has a lot of support. Even if there were irregularities in the election, and that still has to be proven, he still has enormous support. At least close to 50 percent, if not more. This is despite being in power for quite a long time.

It’s interesting because the narrative has kind of flipped. I remember articles in The Washington Post and elsewhere that pointed out that contrary to most of the governments in the region, Morales has had a very strong social and economic legacy. In terms of the macroeconomic figures, that was quite obvious where you had a strong rate of growth.

But also policies that helped with the redistribution of income – various cash transfer programs and so on – hat were instrumental also in reducing inequality and bringing millions of people out of poverty in that country.

People who look at Venezuela's collapse and say "See, socialism doesn't work!" should look at Bolivia.

Since Evo Morales came to power there has been rapid, sustained, unprecedented growth in living standards, along with a massive drop in inequality. pic.twitter.com/gKG6PMSPsN

— Noah Smith

(@Noahpinion) December 29, 2018

Of course, that benefited primarily the indigenous majority of the country, which has been – most of the indigenous people in Bolivia are in the lowest income strata.

Certainly, most of those people and most of those communities are better off in terms of their current income levels, but also in terms of education and health and so on. That’s a very strong legacy. And that’s what made him still a very viable candidate in these elections. And so that was reflected on a lot initially in the media narrative.

And now the narrative has been focused more on the fact that he sought re-election and organized a popular referendum [in 2016] to amend the Constitution because there’s a term limit in the Constitution of two terms. And so there was this popular referendum which he lost by a small margin, but he lost that referendum.

But then the Supreme Court ruled in favor of his re-election. And so technically, it was a legal thing for him to run for re-election, but it obviously generated a lot of controversy and that’s something that a lot of the media have been focused on.

And we’re also seeing from various pundits this idea that, ‘well, he kind of deserved what he got because he messed around with the Constitution.’ And it’s rather disturbing because this was a full-fledged military coup and it could have very ugly consequences.

At the moment, you have a vacuum of power that in itself is somewhat dangerous. And now you have a big counter-protest movement coming from Morales supporters who are not taking this lying down.

So now we’re looking at an increasingly dangerous situation, particularly as the armed forces and police seem to be very, very politicized and taking the side of the opposition. And with Carlos Messa taking a back seat, you have figures like Luis Camacho, who is a fundamentalist evangelical who comes from a very racist, anti-indigenous movement that was very violent and active during the beginning of Morales’ presidency.

So things could get very ugly very quickly. The people who are vying for power, some of them are saying, ‘okay, we’re going to have elections very soon.’ But what kind of elections can you have when you have a big sector of the population that’s under attack and when you have the leaders of what was the governing party that are now – in many cases – in hiding or seeking exile?

And it’s hard to imagine very free and fair and inclusive elections taking place in this kind of context.