The United States, on February 29, signed an agreement with the Taliban that aims to end America’s longest overseas war.

During the 18-year conflict, the U.S. and its allies lost 4,030 servicemen and women, while the financial cost of security, development, and humanitarian aid to Afghanistan has surpassed a trillion dollars. Through its Official Development Assistance alone, Washington has disbursed nearly $30 billion of aid to Afghanistan.

The Taliban, on the other hand, lost over 144,000 fighters between 2002 and 2018, according to the Uppsala University Conflict Data Program. For Afghanistan, the same source records over 150,000 security and civilian causalities.

This data reveals the tremendous cost of the Afghan war for all parties involved. What are the prospects for peace now that the U.S. and the Taliban have signed their agreement?

Peace in Afghanistan

The accord is an important first step but lacks a tangible significance for bringing peace. The deal, at least what has been circulated on Afghan social media, points to one thing: the U.S. is no longer interested in making war in Afghanistan.

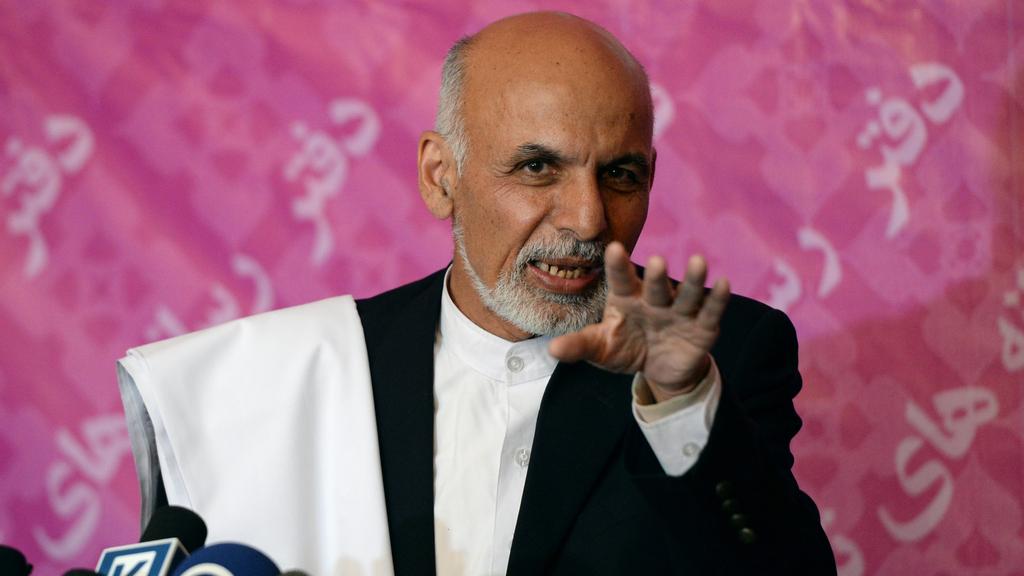

Months of negotiations led by U.S. Envoy Zalmay Khalilzad show that Washington has calculated its exit strategy. The agreement’s most commonly reported downfall is Afghan President Ashraf Ghani’s objection to the deal’s arrangement that would see the release of 5,000 Taliban prisoners from Afghan government prisons.

However, the U.S. bypassing the Afghan government is not the real challenge. The problem is far deeper and more precarious.

Issues Undermining Peace

The Taliban does not recognize the government in Kabul and may only agree to engage in dialogue with a group of Afghan elites and perhaps a small Jirga (Council of the Elderlies), which has a historical presence in Afghanistan to resolve state issues.

Conversely, President Ghani maintains a narrative that echoes the voice of law and constitution from his official position. This ushers in a central challenge: neither Ghani nor the Taliban will compromise on their own.

Yet, even this is not the real issue. As a “peace” agreement, the U.S. has gravely miscalculated the capacity of the Afghan political elites to form an alliance against the Taliban, to fight or to make peace. Indeed, the U.S.-Taliban agreement neglects two fundamental issues that continue to undermine the possibility of peace in Afghanistan.

Afghanistan’s Political Deadlock

First, it fails to address the ensuing political deadlock that has gripped the war-torn country since the presidential election in late 2019. The turnout was historically low, with less than 2 million from the 9.6 million registered voters heading to the polls.

When President Ghani told his international partners in Geneva that his government should not be sidelined because “peace has to be Afghan-led and Afghan-owned,” he wanted one thing: support for a second term. Allegedly, the only supporters he could garner were from the Afghan Independent Election Committee, who rushed and announced the final results – Ghani’s victory – just a few days before the U.S.-Taliban agreement.

After the announcement of Ghani’s victory, only a few foreign officials congratulated him for securing a second term, while others have been hesitant to do so. In contrast, his opponent and partner in the Afghan National Unity Government, Abdullah Abdullah, has denounced the election as rigged, claimed victory, and announced to establish his own “inclusive government.”

Socio-Ethnic Fragmentation

This leads to the second issue. Despite progress in some areas, President Ghani’s five years of leadership has fragmented Afghan society and its political arena further than ever before.

The 2019 votes were divided between Abdullah in the north and Ghani in the south. This is where the challenge lies. Neither the United States nor the international community has fundamentally dealt with Afghanistan’s socio-ethnic fragmentation, and there has never been a genuine political settlement established in the country.

It wasn’t created with the 2001 Bonn Conference, nor was it established in the 2014 intervention by then U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry to form a diarchic government in Kabul under the Afghan National Unity Government. This unity government has further divided the political elites between the traditionalists and technocrats, with each bringing their own sets of tensions and challenges to the table.

Quest for Peace

Of course, the U.S.-Taliban agreement could have facilitated peace in Afghanistan if it contained political settlement initiatives and a means to break the political deadlock. With or without the U.S., the Afghan political system is extremely fragile, fragmented, and lacks a unified narrative against the Taliban.

Despite being an important step, the significance of the U.S.-Taliban agreement for the Afghans faded instantly as the Taliban ended their week of “reduction in violence” with a bomb attack that killed three people. On March 3 alone, the Taliban conducted 43 attacks on the Afghan National Defence Force in Helmand Province, which was responded to with U.S. airstrikes.

No peace for the long-suffering civilians of Afghanistan: Taliban bomb a football match, killing three people. https://t.co/Qn6fukT8OI pic.twitter.com/E9KZMoCIJQ

— Andrew Stroehlein (@astroehlein) March 3, 2020

If anything, the deal made ordinary Afghans think that they are on their own, similar to when the Soviet Union left the country in 1988. At the same time, Ghani’s objection to releasing 5,000 prisoners only through an Afghan government initiative is the strongest bargaining-power he has left to re-instate his version of a “roadmap for peace.”

The most significant challenge is to establish a strong, unified narrative on the Afghan side to seize the opportunity and negotiate with the Taliban. But as long as the Taliban and other domestic rivals do not recognize President Ghani’s government, the quest for peace has to continue in this war-torn country.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of The Globe Post.