In October of 2019, Chile was shrouded in social protests, metro boycotts, and violent policing. Millions of people poured into the streets to demand some sort of change, whether that be a new government, a better life for working-class Chileans, or a new constitution.

Almost exactly one year later, the same streets erupted with jubilation at the news that the 1980 constitution, written under dictator Augusto Pinochet, will be replaced by a new text, drafted by an elected constitutional assembly and voted on by the people.

While some Chileans continue to protest against the state, others begin to discuss the materialization of their plebiscite result. For the first time in its modern history, the South American nation has an opportunity towards a more authentic democracy. Not only is it nationally significant, how Chile includes its citizens in the constitutional process could become a model for reform in democracies around the globe.

During the run-up to the constitutional referendum, Chilean professor and political scientist Claudio Fuentes has been hosting civics workshops throughout Santiago. In this interview, The Globe Post speaks with Dr. Fuentes about the history of Chile’s constitutions, social conditions that led up to this moment of change, and the promises it beholds for the people of Chile.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

The upcoming constitutional assembly of 155 people next April will have mandated gender parity. What’s the significance of that?

Fuentes: It’s pretty relevant. Of all the demands among the citizens, the strongest was gender equality. The feminist movement plays a crucial role in those demands, particularly after the MeToo movement in 2015, 2016. That history explained that the eruption last October required certain social conditions, one of them being the realization of the feminist moment that happened before. This is why it’s not surprising to have a parity in the convention.

It will be the first time in the history of humanity that a constitution could be written in equal terms by women and men. And I think that is due to the feminist movement that not only protested but also provided an alternative for politicians to set up that rule. They were very effective. The Chilean Political Science Association, for instance, is led by a woman. The network of women works with deputies and senators. So that is very relevant.

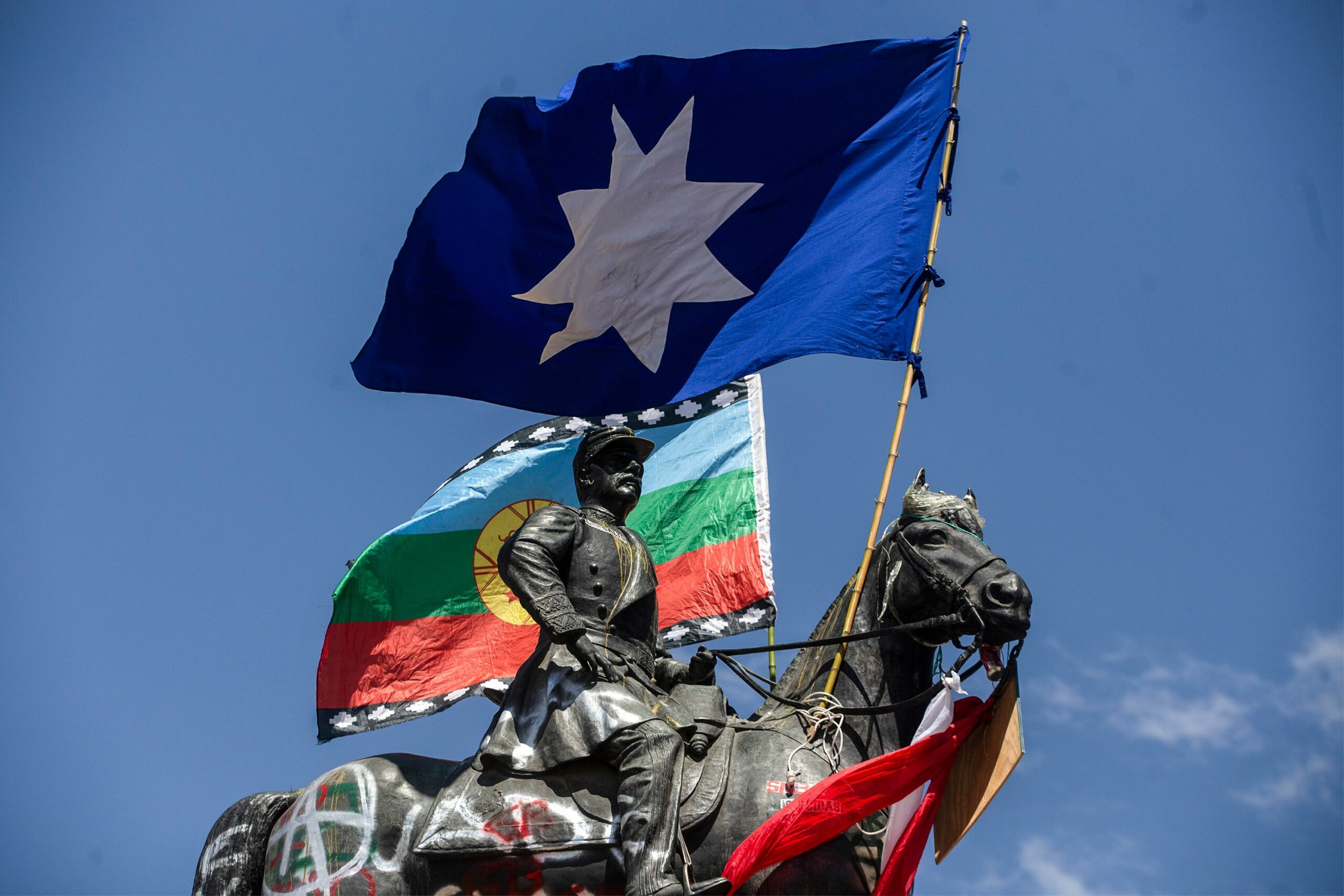

By the same token, how are the Indigenous peoples of Chile going to be incorporated into the convention?

Fuentes: That is an interesting contrast. As you have parity for women and men, they are still debating whether we will have reserved seats for Indigenous peoples. There is not an agreement to date. So we don’t know if the convention would include reserved seats for Indigenous peoples, even though the movement is very strong and Indigenous peoples represent 13 percent of the population.

Chile is headed into quite an eventful year in 2021. There’s the constitutional assembly, but there will also be a presidential election in November. What worries you about how these political activities are going to affect the constitution?

Fuentes: Oh yeah, that is very inconvenient, having a debate of a new constitution and having an electoral dynamic within that process. I think it’s not the ideal situation.

It’s problematic because the incentive of the politicians in an electoral year might contaminate the debates about the constitution. Those that are elected for the convention will for sure be debating presidentialism or the term in office. They will look at who will win the election to define what kind of term in office we might have. So it might affect and contaminate the debate about the rules, particularly on the distribution of power within the country.

The plebiscite was supposed to take place in April, but it was delayed because of the pandemic. How has the coronavirus affected the results of the referendum?

Fuentes: In Chile we have 345 municipalities. Only 30 were in a total restriction for the election because of high levels of COVID exposure (people could still go and vote and get back to their places). In those 30 municipalities, participation went down around 10 points.

The rest of the country did not suffer a strong effect from the pandemic. Just over half (51 percent) of the people went to vote, which is a little higher than the presidential election. But it was not such a strong level of participation. We have, particularly in the younger generation, some groups of society that do not participate in elections, like in the US, as you may know.

Now you bring up the issue of turnout. The constitution applies to everybody in Chile, but if only 51 percent of the people showed up to vote and agree to have that constitution, what kind of issue do you think this will bring?

Fuentes: Yeah, 80 percent of voters showed support for the idea of having a new constitution, which I think was a strong message. If the situation was something like 60-40, then we would probably be debating the legitimacy of the plebiscite. But it was 51 percent. And of that 51 percent, 80 percent support the idea of having a new constitution. So the legitimacy issue is not in debate anymore.

We will have an elected convention and one year after we will have a ratifying plebiscite with mandatory voting. So the design is that you have the mandatory plebiscite for the ratification of the new constitution, which I think is useful.

Why was the old constitution, the 1980 constitution, so unpopular among the Chilean people?

Fuentes: Well, the first reason from a lefty point of view is that it was Pinochet’s constitution, and it was approved or promulgated during the military regime. But I think that the criticism goes beyond that.

It’s about the way the constitution sets certain rules, like for instance, the rule of the market. In general, the Pinochet constitution provides a very open space for markets to develop in crucial areas like the pension system, the health system, in which the state doesn’t have a role within these main social sectors. That is one issue.

The second issue is that within the constitution, certain key issues like water rights are approved for the private sector, which is very unusual in the world that the right to water is privatized.

And finally, the very weak role that citizens play within the constitution. You have the congress and the president, but there are no mechanisms of strong or decisive participation of the citizen within these institutional frameworks, which is another demand.

You were leading projects and workshops on teaching people about the constitution. Tell me about that experience. What was the interest in the students? Were there a lot of people interested in learning more about the democratic process?

Fuentes: Yeah, I used to have a project on constitutionalism. I went to several more public neighborhoods in Santiago and started having what we call cabildos, which are roundtable meetings. Some 20, 30 people get together and talk. And I started listening to them.

At the beginning, right after October 18 of 2019, I was trying to understand what was going on, understanding the discourse, what the people are talking about. In general, people were afraid. A lot of uncertainty was living in Santiago.

Secondly, they wanted change. They wanted to have the idea of social justice, of ending corruption. There was a lot of criticism towards politicians and very strong anti-party kind of discourses, which is problematic because the parties in Chile have played a very strong role in intermediating between the citizens and the state.

A lot of people expressed fear at the lack of institutions supporting them. You don’t have the state in many of these places. You have people trying to survive debt, working long hours of the day alone.

And so the feeling is a need for a new social embeddedness. I think that behind the debate about the new constitution, is the people wanting to have a new social path, a new way of socializing in Chile.

In this New Yorker story, there’s a scene where you were teaching a group of students and the entire room of them answered “no” to the question of whether Chile is a democracy. Why do you think there’s a disconnect between the people and the representatives, even though Chile is technically a democracy? Why do you think there’s that lack of participation?

Fuentes: There are two or three factors to explain that response. I have continued doing those workshops and asking that question, and usually the response is the same.

One factor is what you mentioned, participation. The feeling of the regular citizen, not the elite, is that this political system in the last five or 10 years has had a lot of corruption. Citizens perceive that there is this cleavage between the elite and the people, el pueblo. And the normal citizen is saying, “enough of this. The elite has been screwing up everything. They are corrupt right now, they’re not the same politicians as in the past. They are usually serving themselves and not the people,” et cetera.

The missing link here is that I am electing you and you are not representing my interests, but your own interest. So that is the first criticism of this weakening democracy.

The second aspect is very related to what happened after October 18, 2019, because of police violence. Police violence increased and became a huge issue. We hear news stories where people had their eyes shot and other violent repressions by the police during protests. That provided stronger criticism from the citizens to say that this government is becoming authoritarian, using force against the people, that they are not understanding that these are legitimate protests.

And finally, you have a state of exception. The government declared a state of siege that created more restrictions over liberties. We have restrictions at night, we can not move. And this was before the pandemic. So we have a situation in which citizens are perceiving that these representatives are not representing my interests, and they are repressing our mobilizations; so this is not a real democracy.

If you take off your scholar hat and put on your everyday citizen hat, what do you personally hope will be included in the new constitution?

Fuentes: I think that the social rights that are in the constitution are very weakly defined. So probably I would expect a stronger definition of certain social rights, particularly in health, housing, the pension system reform, water, of course, that kind of issue.

And probably a better definition of what a democracy is about, with stronger participation of the citizens within decision making.

Chile has had 10 constitutional texts in its history, but none were written by the people. What gives you hope that this will be the opportunity for a more legitimate democracy?

Fuentes: Some days I wake up with hope and some days not. It’s been up and down. My concerns are related to the crisis of representation of the political parties. We are probably living in the strongest crisis since the early 1920s. So for me, the political parties and the representatives are problematic because nobody wants to be close to the political parties and probably the political parties will play a very strong role within the constitution.

Now, the hopes are related to citizens. Citizens are very aware that this whole process could not be successful without them. So there is a lot of debate in Chile about establishing mechanisms of citizen participation, in parallel or in contribution to the convention.

It would be interesting to see whether we will have a participatory mechanism to open up the assembly and allow citizens to participate in the definition of this new constitution.