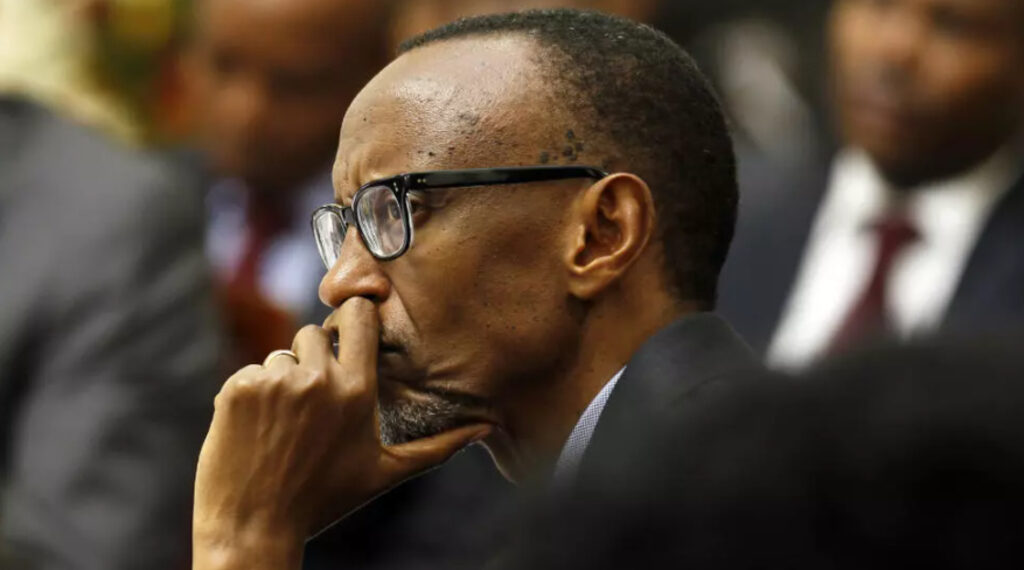

Rwandan President Paul Kagame says France’s recent acknowledgement over its role in the 1994 genocide in his country is “a big step” — even if it didn’t come with an apology.

His counterpart Emmanuel Macron, during a historic visit to the east African nation this week, recognized France’s role in the killing of 800,000 mostly Tutsi Rwandans and said only the survivors could grant “the gift of forgiveness”.

Stopping short of an apology — and stressing France “was not complicit” in the actual violence — Macron went further than his predecessors in acknowledging that Paris backed the genocidal regime and ignored warnings of looming massacres.

Some survivors had been hoping for a formal atonement, and were left disappointed.

But Kagame, who lead the Tutsi rebellion that ended the genocide, has regularly accused France of complicity in the crimes.

He applauded Macron for “speaking the truth” and said his words were “more valuable than an apology”.

Expanding on his remarks in an interview with AFP and France Inter, the veteran Rwandan leader expressed doubt about ever “getting an entirely satisfactory answer”.

“But I think it is a big step. We need to admit it, take it and work towards other steps, whenever and wherever they come,” Kagame said late Friday in Kigali.

“Somebody can come and say ‘I am sorry, I apologize’. Still, I think some people will remain and say ‘that is not enough’. And they have the right to think so or to say so. In this case, I don’t see a silver bullet, something that will come and settle everything.

“Does it answer everything, every question that everyone has to raise? I don’t think so. Do survivors have the right to question a number of things? They have the right.”

Deliver justice

Macron’s visit, the first by a French leader since 2010, sought to turn a new page on a tortured quarter century of acrimony between France and Rwanda over the unresolved questions of the genocide.

Ahead of his symbolic trip, Macron had commissioned historians to pore over archives to re-examine France’s involvement not just in the brutality of 1994 but the crucial years leading up to it.

France provided political and military support to Kigali during a civil war preceding the genocide, and long stood accused of turning a blind eye to the dangers posed by Hutu extremists in a country scarred by large scale massacres in its past.

The Duclert Commission report, handed directly to Macron, accused Paris of being “blind” to preparations for the genocide, and said it bore “serious and overwhelming” responsibility.

A Rwanda-commissioned report into the same events, released just weeks later, said the French government “bears significant responsibility” for enabling the genocide in Rwanda, yet refused to acknowledge its true role in the horror.

Kagame said the two commissions “say almost the same things, but in different ways”.

He asked that Macron honor a commitment made during his visit that anybody accused of genocide crimes in France face justice — but did not insist on their extradition.

“If justice happened in France against these people, I am happy. I don’t have to say ‘it will only be justice if you bring, give them to me and we trial them in our courts’. Justice is justice. If France wants to trial them, that’s what they should do,” he said.

“I am not particular about the form. I am particular about saying these are people that have serious crime against them, they should be held accountable one way or the other. It is not for me to decide who, what, where.”

He declined to comment on the Paris prosecutor’s request this month to drop a case accusing French troops of complicity in crimes against humanity over their inaction in a massacre.

“It is not for me to decide,” he said.

‘We are fired at’

Kagame said the recent rapprochement, though not perfect, lays the foundation for “a better and maybe deeper relationship between Rwanda and France”.

But critics accused Macron of remaining silent on Rwanda’s murky record on rights and freedoms in the pursuit of reconciliation with Kagame, who has kept a tight control on the country since the genocide.

Kagame said the accusations leveled against his government were largely baseless and stirred up by outsiders.

“When it is here, our problems must be addressed by the outside. Or actually created now by the outside,” he said.

“Everyday we are being fired at. A lot of lies, hundreds,” he added.

Taking power in the aftermath of 1994, and the presidency in 2000, Kagame had the constitution amended in 2015 to allow him, at least in theory, to remain in power until 2034.

The next election in 2024 is still too far away to consider, he said.

“I don’t think about it much, I don’t worry about it,” he said.