Copa América, the oldest still-running continental football competition, just wrapped up across the United States pitches. Although the hosts were eliminated early, thousands of supporters remained following the matches and cheering for their national teams.

The first edition of the Copa — then called South American Championship — was held in 1916 in Buenos Aires, with the aim of celebrating the centennial of Argentina’s independence. While Uruguay won, the competition’s political purpose was achieved as it marked Argentina as an autonomous country.

Since then, politics and football have been entangled in the social fabric of South America.

Broader Movement

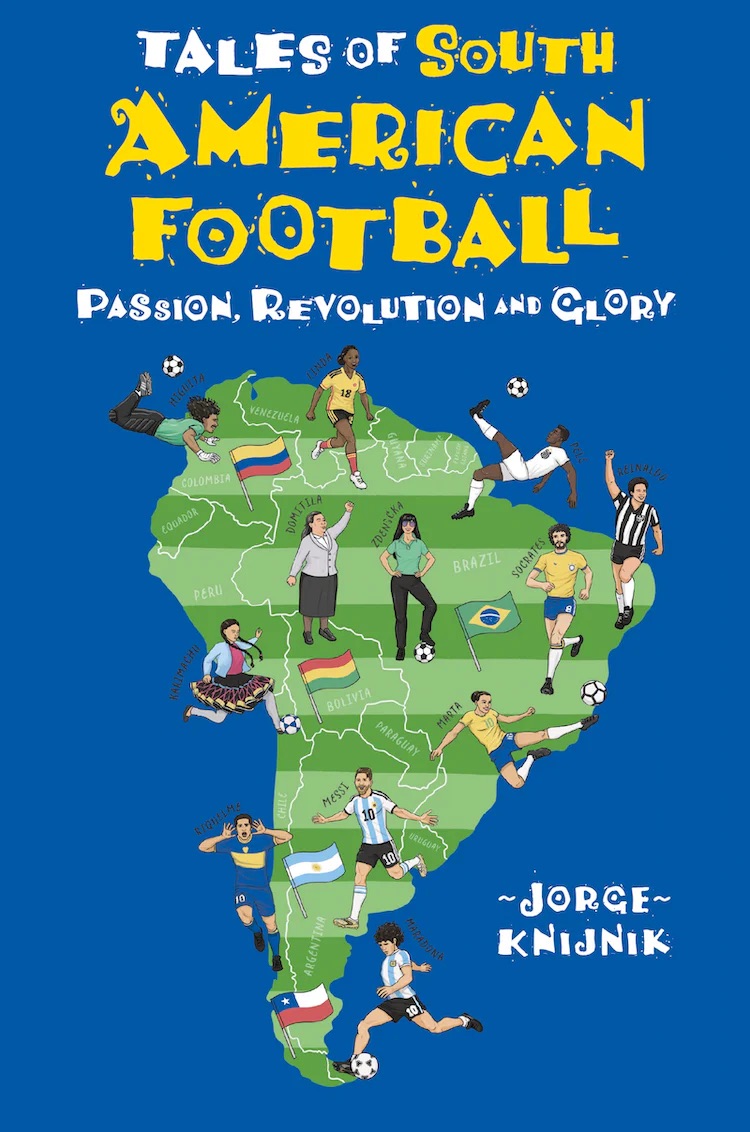

In my recent book Tales of South American Football, I show how football is a potent political tool for South Americans. This is particularly true for Uruguayans, Argentinians, and Chileans, who seek truth and reparations for the crimes committed by the military dictatorships that spread terror within their populations in the 1970s and 1980s.

Throughout these societies, football is a key component of the struggle for memory and historical compensation. The hinchas (football supporters) have taken these battles to the terraces, identifying human rights abusers among their members and calling for justice within their football clubs.

The hinchas’ demands are part of a broader movement of transitional justice, a method to address organized or immense abuses of human rights that mutually offers reparation to victims and produces or increases prospects for the renovation of the political structures that might have caused the crimes.

Hinchas con Memoria

The acclaimed Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano, author of Soccer in Sun and Shadow, once wrote “Uruguay does not have history, instead it has football.”

During the late 2010s, several Uruguayan football supporters’ groups commenced new political campaigns to fight this lack of memory, reinstitute historical truth, and avoid oblivion.

These campaigns aimed to both remember the crimes their dictatorships committed to members of their clubs and to expel from their associations people who had been found guilty of severe abuses during the military reign.

In 2021, the movement hinchas con memoria (fans with memory), formed by supporters of the Uruguayan Club Atlético Peñarol, celebrated the final achievements of its 2018 crusade called Gol contra la Impunidad (Goal Against Impunity).

This campaign aimed to expel the club militaries already convicted by their participation and leadership during Operation Condor — an international collaboration between several South American countries that functioned across borders between the mid-1970s and the early 1980s, aiming to systematically exterminate political opponents.

In this celebration, the young supporters were joined by Alba González, an 87-year-old mother whose son disappeared in 1976 during Operation Condor in Argentina.

At her age, González was still an active participant in the Uruguayan associations of mothers and relatives of people who disappeared during the military government. This symbolic moment showed how different generations of Uruguayans are unified and strong in their fight for memory and justice.

At the start of its activities in 2018, the Goal Against Impunity campaign had already succeeded in banning Miguel Zuluaga from the Peñarol membership.

Zuluaga was a brutal torturer who worked for Uruguay’s intelligence department during the military dictatorship. His interrogation methods were so ruthless that his colleagues nicknamed him El Zulu.

Notwithstanding his role in the disappearance and killing of countless Uruguayans, Zuluaga was employed by the Uruguayan Football Association and worked as head of security of the national team from 2000 to 2018, when he was finally fired after intense social pressure that started with the Peñarol hinchas campaign.

Pictures of Zuluaga hugging Uruguayan striker and former Barcelona player Luis Suárez or shaking hands with celebrated Uruguayan national coach Óscar Tabarez could be seen in placards during the Peñarol supporters’ street protests. Zuluaga’s story is clear evidence of the complex and problematic relationship between football and politics in Uruguay.

Dictators Expelled

In the early 1970s, Club Social y Deportivo Colo-Colo (or just Colo-Colo) was the main Chilean football club. They were so relevant that in 1971, Salvador Allende, the socialist president who supported Colo Colo’s rival La U (Club Universidade de Chile) once said that only Colo-Colo could unite Chileans over any common cause.

Once in power, Augusto Pinochet, the bloody dictator who led the coup d’état that ejected Allende from the presidential chair, was quick to organize for the club’s management to nominate him as the president of honor of Colo-Colo.

Coerced by the dictator’s brutal tyranny, Colo-Colo members waited for many years. Then, only in 2015, an assembly of members approved erasing all records of the dictator from the club’s history. They noted that the appointment of Pinochet as member and honorary president was “illegal and illegitimate.”

The Colo-Colo supporters’ action ignited a wave of deeds by South American football clubs and their supporters to establish truth and history and reinstate justice among their members.

Following the Chilean example, on March 24, 2021, when Argentineans celebrate the National Day of Memory for Truth and Justice, the powerhouse Boca Juniors held a ceremony to remember the 30,000 people who disappeared in the country during a period called State Terrorism.

Alongside members of the world-known human rights movement Mothers (and Grandmothers) of Plaza de Mayo, the Argentinean Football Federation’s president, and the captains of Boca Juniors and Defensores de Belgrano, the club’s president planted a tree to honor those who fought the dictatorship.

At the same time, the club announced the dissolution of the membership and positions held by agents and leaders of the dictatorship, such as Emilio Eduardo Massera. Admiral Massera, who was granted the title of honorary member in 1972, was one of the three members of the military junta who led the dictatorship between 1976 and 1978.

Football and Transitional Justice

Reparation for victims is as important for transitional justice as prosecution of culprits. These can involve money when victims seek compensation for financial difficulties they suffered after their providers were killed by the barbaric political regimes that disgraced South America in the 1970s and 1980s. However, reparation also includes symbolic acts that re-establish truth and preserve historical memory.

Bearing this in mind, the Argentinean Club Atlético Huracán in October 2021 paid tribute to eight of its members who disappeared during the dictatorship.

In a touching ceremony, the club reissued the members’ identifications and offered them to their families. The club also inducted an honoring artistic montage for them. This artwork, which has human rights as its central topic, was installed on a wall in the club’s stadium to preserve the memory of those who suffered atrocities during the military period.

Ongoing Process

Transitional justice is an ongoing process in many South American societies. While much has been achieved, there is still more work to be done to recover the truth, prosecute and punish the culprits, and compensate victims and their families.

There are countries, such as Brazil, where that process has been slowed down by right-wing governments. In South America’s largest nation, even though a few families have received compensation, no criminal or torturer has been convicted.

Nevertheless, football has helped achieve transitional justice objectives for institutions, victims, and culprits in Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay. In these nations, being on a football stand is so relevant for community cohesion that the idea of cheering on your beloved club alongside someone who committed crimes against humanity is unbearable.

“Football is never (only) about football.” Copa America truly breathes new life into this old slogan.