At least 10 election candidates have been killed, thousands of polling centers closed, and many voters are likely to stay home due to the threat of militant attacks.

This is democracy, Afghanistan style.

Almost nine million people have registered to vote in the October 20 parliamentary election, which is more than three years late and only the third since the fall of the Taliban in 2001.

But shambolic preparations, expectations of industrial-scale fraud, and escalating poll-related violence threaten to derail the election, which the international community is advising and largely funding.

A powerful Afghan police chief and a journalist were among at least three people killed on Thursday in the latest attack leading up to the elections when a gunman opened fire on a high-level security meeting attended by top U.S. commander General Scott Miller, officials said.

The Taliban said the attack had targeted Miller, who NATO said survived the shooting.

Alarm is growing as the beleaguered Independent Election Commission (IEC), which has been skewered for its poor handling of the process, struggles to distribute voting materials to more than 5,000 polling centers before they open at 7:00 am on Saturday.

They are supposed to include biometric voter verification devices that Afghan political leaders and officials only agreed to use a few weeks ago and have been made mandatory, despite being untested and not required by law.

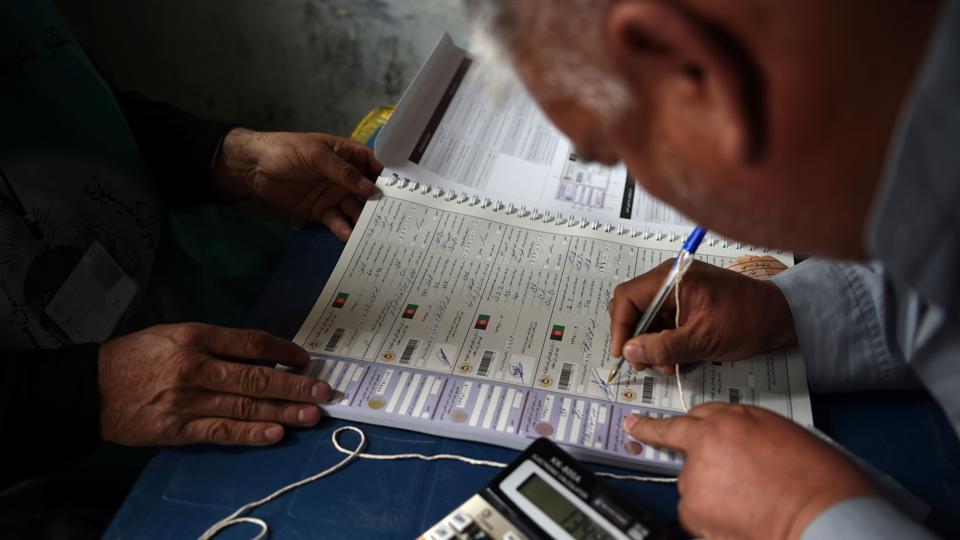

Votes cast without the controversial machines will not be counted, IEC spokesman Sayed Hafizullah Hashimi told AFP, even though polling center workers have received little or no training in how to use them.

Observers are concerned the results could be thrown into turmoil if the devices are broken, lost or destroyed.

“We’re trying to make a terrible situation slightly less bad,” a Western diplomat told AFP, reflecting a sharp drop in expectations for a credible result, even by Afghan standards.

There also are fears the data could be manipulated before preliminary results are released on November 10.

“Using technology can help transparency but it can also create confusion if not used properly,” said Naeem Ayubzada, director of the Transparent Election Foundation of Afghanistan.

‘Pseudo-Democracy’

More than 2,500 candidates are competing for 249 seats in the lower house, including doctors, mullahs, the sons of former warlords and at least one prisoner.

Campaigning has been marred by bloody violence. At least 10 candidates have been killed so far, including Abdul Jabar Qahraman who was blown up Wednesday by a bomb placed under his sofa in the southern province of Helmand.

The Taliban has warned candidates to withdraw from the ballot, which it has vowed to attack, and told education workers to stop their schools from being used as polling centers.

Senior Kandahar leadership including police chief Gen. Abdul Raziq are said to have been killed in the attack claimed by the Taliban https://t.co/KeRQyYNmhE

— The Defense Post (@DefensePost) October 18, 2018

The election is seen as a rehearsal for the presidential vote scheduled for April and an important milestone ahead of a UN meeting in Geneva in November where Afghanistan is under pressure to show progress on “democratic processes.”

Despite speculation the vote could be postponed again, Hashimi said it had to go ahead on time.

“It is already snowing in some provinces and the weather is getting colder,” Hashimi told AFP.

“If we delay the elections for a week, it means we won’t have them.”

Observers expect turnout on polling day to be far lower than the 8.9 million registered to vote in the first legislative election since 2010.

More than 2,000 voting centers have already been closed for security reasons, and the threat of more militant attacks are likely to persuade many voters to avoid the poll.

Some 54,000 members of Afghanistan’s already overstretched security forces will be deployed to protect the ballot.

To help boost numbers, Hashimi on Wednesday urged the media to focus on the elections, not violence.

There are widespread suspicions that a significant number of voter registrations were based on fake identification documents, which fraudsters hope to use to stuff ballot boxes.

Registrations in the eastern province of Paktia, for example, were “an implausible” 141 percent of the estimated eligible population, Afghanistan Analysts Network (AAN) said in a recent report.

“The fraud is already baked in,” a Western diplomat told AFP, adding Afghan officials may never know how many people actually voted.

That has further eroded confidence and deterred potential voters.

“Most of the people I have been talking to say they won’t go to vote, some even didn’t bother to register, and many said ‘we would love to vote if we knew the system would work’,” AAN co-director Thomas Ruttig told AFP.

“It’s not that Afghans are tired of democracy. They’re tired of this kind of pseudo-democracy.”