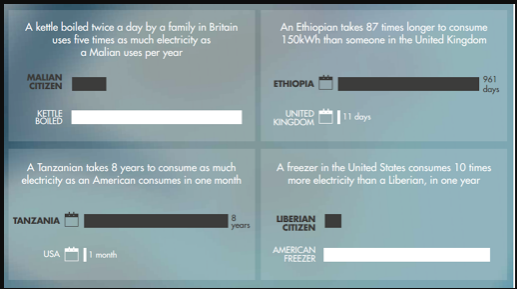

On any given day, lobbyists, lawyers, and business people in marble offices on Washington’s historic K street utilize the same amount of energy as the entire nation of Liberia. And in Nigeria, the average citizen consumes just 1 percent of the electricity of the average American citizen.

These jarring energy disparities affect 3.8 billion people across the planet – nearly half of the world population – but are most dire in Africa where only 25 percent of people have electricity at home.

But while increasing access to lights remains a key first step in mitigating energy poverty, full-scale energy needs extend much farther to encompass greater access to clean water, infrastructure development, and technological innovation – all prerequisites for job creation and growth.

As Todd Moss, the CEO of Energy Hubb told U.N. Dispatch, “If the future of Africa is low energy, that’s a jobless future.” Because, as Moss states, “Energy is an accelerator for the wider economy that serves as a bridge to assessing the entire human potential.”

Yet African energy development was not a focal point of the 39th Annual CERAWeek in Houston last month, where senior energy executives, innovators, and global stakeholders in the energy industry convened to discuss the future of the energy sector. Instead, climate change, digital technology, U.S. dominance, and gender diversity in leadership took the foreground of themes discussed.

With the acceleration of climate change taking center stage at CERA, talks of transition to renewable energy were widely endorsed by cross-sector leaders. How to best meet that need, however, remained contentious. Bottom-up, market-oriented mechanisms were favored over the U.S. proposed Green New Deal, an ambitious bill met with much disdain by the business-centric audience.

One of these bottom-up approaches has made substantial inroads to energy poverty alleviation in Africa, and sparked the attention of Jem Percoro, Senior Director for Energy Access at the United Nations Foundation, who expressed that “there’s this incredible market opportunity that’s not being met by the relatively small handful of companies that are operating on the continent.”

The renewables revolution, like the off-grid solar market, launched by Nairobi-based M-KOPA in 2012, provides low-income families in Africa a “pay as you go” model of energy for as little as $1 per month.

Through the purchase of an individualized “kit,” homes gain access to services such as a solar panel, battery, power sockets, LED light bulbs. Payment is made available through a metered payment system on a sim-card, and the low-cost-to entry and ease of installation of these kits minimize many of the challenges that centralized energy sources require.

Since M-KOPA’s inception, the diversity of off-grid options is increasing as new companies enter the market including Uganda-based FENIX, U.K.-based BBOX, the Netherlands-based ZOLA, and Dutch Startup Lumos.

The off-grid solar market is now estimated by the World Bank to see sales of $8 billion by 2020.

For many of these private companies, the returns both on investment and human capital for people in Sub-Saharan Africa are steadily increasing. Courtland Walker, the managing director at Developing World Markets, a large investor in the off-grid solar market, told The Globe Post about the pattern of market growth he expects to see over the next 5-10 years.

“As the underlying technologies continue to improve – including in particular storage technologies—costs go down, and businesses scale to reach profitability, this will create a virtuous cycle where they are increasingly able to drawn on commercial financing – both debt and equity – for growth and thus to scale their businesses significantly,” Wlaker said.

#DYK: Half a million premature deaths occur for children under 5 due to inadequate energy https://t.co/ZcwowWGxey #SDG7 #EnergyAccess #EnergyPoverty #offgrid pic.twitter.com/YBaGVOuKw5

— Power for All (@Power4All2025) March 31, 2019

The private sector is increasingly being joined by multilateral coalitions of nations and elected officials willing to step up their commitments to renewables and increased energy access in Africa.

Kenya’s President Uhuru Kenyatta has announced his aggressive plan to achieve a 100 percent “green” energy goal by 2020 and theSwedish Government has pledged an additional $50 million to expand electrification efforts to Burkina Faso, Liberia, and Mozambique over the next five years, following the success of their “Beyond the Grid Fund for Zambia”, a five-year programme implemented by REEEP, which aims to electrify 1 million people. This new Beyond the Grid Fund for Africa will be implemented by NEFCO and REEEP.

In Zambia, Sweden and REEEP are on track to provide electricity to an additional 600,000 people over their initial goal.

In total, estimates of 60 million people in Africa now use off-grid solar power, and Africa’s electrification deficit is falling for the first time ever. According to 2018 Lighting Global Report, the potential market remains “vast” at 434 million households.

But Alexandra Soezer, the climate change technical advisor at the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), suggested caution when looking at the positive trends that smart grids have provided to developing countries around the world.

“The actual share of renewables has dropped most recently, according to the 2018 African Energy Data Book. The data show a growing dependence on fossil fuels and reliance on cost-intensive, centralized power systems that cannot reach the scattered villages in rural settings,” she told The Globe Post.

Reflecting this mixed picture of progress, the world is not on track to meet the Seventh U.N. Sustainable Development Goal for 2030, “access to affordable, reliable, and sustainable and modern energy for all.”

The World Economic Forum has emphasized the need for greater policy and economic frameworks to meet these needs, while Soezer cited greater implementation of flexible grids as a pivotal accelerator of energy access.

With the capacity to “grow basically unlimitedly and increase electricity generation and storage capacity,” Soezer reflected, flexible grids have “a key role to play” in order to achieve Sustainable Development Goal 7 and to mitigate the energy poverty afflicting two out of three people in sub-Saharan Africa without access to electricity.