The amount of displaced peoples in the world is greater than the current population of the entire United Kingdom. The increasing numbers of migrants have been fueled by the climate crisis, conflict, and arbitrary persecutions.

On top of this, refugees have had to endure the coronavirus pandemic with little help from the traditional global leaders. This has resulted in confusion and sickness in displaced communities and has deepened the disparities between the displaced and citizens under a government.

Refugees International provides essential advocacy while promoting solutions to solve issues facing refugees and displaced. The NGO emphasizes its independence from the UN to be able to speak out against both the UN and international laws.

As Refugees International continues their work to support and advocate for the world’s most vulnerable, The Globe Post spoke with Hardin Lang, the vice president for programs and policy at the humanitarian organization.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

The Globe Post: According to Refugees International, there are over 70 million displaced people in the world. Do you think refugees are being kept within the conversation in regards to COVID-19 or have states left refugees out of the conversation?

Lang: I think so far, a lot of the effort has been focused on countries and governments getting a handle on what’s happening within their own borders. People have turned inwards to deal with the nature of the crisis as it’s unfolding in their backyards.

All that said, we have seen some effort to get the process of responding or preparing refugees and displaced communities for the pandemic. Although the time and effort that has gone into it is a fraction of what’s required.

For example, [on July 16] OCHA, the UN humanitarian appeal, came out calling for $10.3 million to help respond to COVID-19 emergencies in humanitarian crisis zones and refugee and displaced camps. The original appeal was $2 billion and then went up to $6.7 billion and now, we’re at $10.3 billion.

However, member states or donors have only committed or pledged $1.64 billion – which is only 15 percent of what is required and that really tells you where the international effort is. This is the largest humanitarian appeal the UN has ever made and it is only fulfilled at 15 percent, which is much lower than even what traditional humanitarian response appeals are at this stage of the game.

The Globe Post: Through this pandemic, we have seen a lack of leadership from the countries we typically turn to, such as the United States. Have other countries taken over that leadership role?

Lang: So, what’s interesting here is that you have a big, traditional leader within the international humanitarian architecture. The United States is largely absent from its old leadership role. It has committed a good amount of money to the effort, but it is not leading the effort which I would hold up as a point of contrast to what we saw earlier in this decade in response to trying to get UN peacekeeping to start stepping up and to have other countries come in and support it.

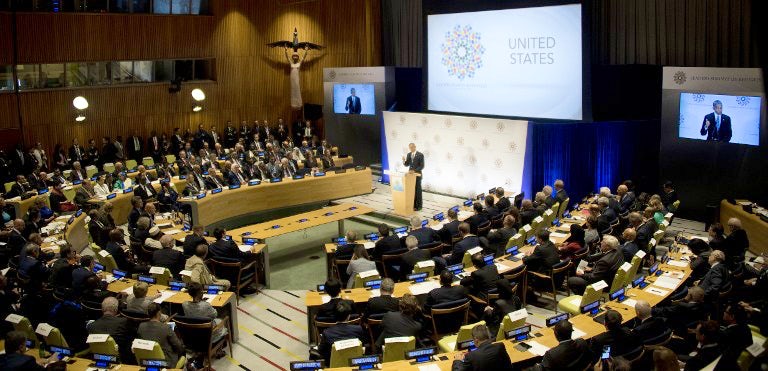

President Obama held a leader summit around the June general assembly [at the UN], not shortly thereafter, in response to the global refugee and migration crisis in 2016, we saw another leader summit led by the United States and then leaders of countries stepping up to make commitments. That’s absent right now. That sort of leadership that pulls everyone together isn’t really apparent at a member state level.

The [UN] Secretary-General is doing his best but it usually requires a few member states. At the global level, we don’t see that level of leadership but what we do see are China and the United States spending a lot more time bickering on the Security Council rather than spending time actually solving the problem.

We see at a regional level, a multi-lateral leadership stand out, for example, the European Union has had its own response. They’ve gotten to the point where they’re actually issuing bonds for the first time at a European-wide level to help fund the response in countries that don’t have the money to see that forward. We’ve also seen European leaders step up on the vaccine front, Angela Merkel and others.

In Africa, we’ve seen the African Union step up and Africa Centres for Disease Control have really played a key effort in helping them at a multilateral, regional level. What we don’t really have is the global, multi-lateral leadership that we tend to expect in this kind of crisis.

The Globe Post: In April, the UNHCR called on states to “manage border restrictions in ways that also respect international human rights and refugee protection standards, including through quarantine and health checks.” Do you think states have successfully done this?

Lang: I think there’s a lot of work to do in this particular area. Over 160 countries have put movement restrictions on their borders in response to the pandemic and in many cases, these are being done solely because it’s a gut response. One country is doing it so others think they should as well. As a result of this, you’ve seen the global window in which the right to asylum is shut.

It has been tremendously difficult and tragic for refugees around the globe. It’s everything from borders in Europe closing to refugees being unable to cross through Libya to Rohingya refugees or asylum seekers in Asia that are now on boats and the boats can no longer dock.

'We have no idea how will we survive'.

The #pandemic is now pushing vulnerable communities into a #hunger emergency.

Find out how you can support our global response to #COVID19: https://t.co/ACiomoCgfE pic.twitter.com/db7wEmlRDi

— ActionAid (@ActionAid) August 10, 2020

Across the board, this has been a huge problem. There’s a differentiation between those countries that are being led by populist leaders that have weaponized the public health concerns around the COVID-19 pandemic, and they are instrumentalizing these public health concerns as a way to justify things they wanted to do politically anyways.

In other countries, they are doing this because they are not sure what else to do, and what we do know [from] talking to the public health community is that there are ways to manage these kinds of challenges.

Public health and asylum are not at odds, they’re complementary and so there are ways to manage people coming into the country, allowing people to seek asylum that can be done in such a way as to protect public health. What we need to see globally is a bigger network to roll back these types of restrictions.

The Globe Post: Refugees International cites misinformation as a big issue within refugee camps. Can you explain the impact that misinformation has within refugee camps specifically during the pandemic?

Lang: We have already been able to see the impact that inconsistent messaging — even within highly developed countries like the United States — has on the spread of the coronavirus. Countries that have taken it seriously and have been very clear about the messaging have seen much better results. New Zealand is a perfect example.

Now if you look at what’s happening in refugee camps, take the example of the Rohingya refugee camps in Bangladesh, so far the number of people that have been officially diagnosed with COVID-19 is under 100 so it’s not bad and a lot of efforts have gone into putting in place containment measures at the camps.

However, if you’re a refugee in Bangladesh, you don’t have access to the internet and you don’t have a cell phone. So the way in which information is spread in these environments, you have a lot of information and for example – you can’t get this if you’re a bad Muslim – rumors spread, and that guides how people respond.

Key things like allowing a free flow of information to be consistent are absolutely critical to the successful response and you don’t even have to look at a refugee camp.

The Globe Post: Social distancing is a critical tactic used to slow the spread of COVID-19 but seems to be very difficult to carry out in refugee camps. Are you finding that to be true?

Lang: It’s extremely difficult to do it in the way that we would want to model it as in a developed, industrialized economy. That isn’t to say that there aren’t things that can be done. For example, the way the World Food Programme is now changing its model for food distribution, instead of having additional lines, they are not spacing it out and using a number of distribution points or in some cases, they’re even doing home deliveries and getting it to the actual house so people don’t even have to leave.

There’s a deep conversation going around about what’s called “shielding,” which is trying to move populations that are particularly vulnerable, like the elderly or people with secondary conditions, into sections of a camp where the protocols around those populations are extremely robust and they’re trying to maintain social distancing and limit access to people who may or may not have COVID-19 coming in.

There are a series of things that can be done: creating more space in refugee camps, creating shielding, changing the way distributions are handled, but all that said, the main point of defense is trying to prevent it from getting into the camp.

The Globe Post: When it comes to COVID-19, the symptoms are not always present in an infected person and it can range from being asymptomatic to needing intensive care. For the refugees that end up in critical condition, how are they able to get the intensive care that they need?

Lang: Very few will be able to. If you look at just the number of facilities within Bangladesh in and around the camps where intensive care is available, there are very, very few. If you look at the numbers in northwest Syria, where you have millions of people displaced by the recent fighting and living in very desperate camp situations, they have around 100 to 200 ventilators to serve the entire population.

Intensive care for these types of communities is always in very, very short supply. The kind of intensive care and the kind of materials and supplies that are required to do what is necessary for people who have the acute respiratory symptoms of the virus is not accessible to most refugees and displaced communities.

The Globe Post: Finally, how do we improve the situation in which refugees and displaced communities have to live in on a short timescale due to how fast we know the virus spreads?

Lang: There are a couple of things that can be done in the immediate: surge the amount of PPE [personal protection equipment], they need access to hygiene, basic sanitation, water points. There are very basic things that they need that you can surge into camps in high numbers. There is the effort to do that inside the UN by a task force that has been put together and the idea is to surge materials into crisis zones and that really needs to be put on steroids.

In addition, one of the things that we’re really noticing across the world is that the pandemic hit refugees and the displaced extremely hard even before the virus itself arrives.

The number of people who are expected to be moved to the brink of starvation is going from 104 million to 276 million people within the year. This is because economies are collapsing and food distributions chains are being interrupted and because local economies and markets are being closed down in response to the virus. This is not the virus directly affecting them but the response itself that is.

The second thing would be food security and the third thing would be jobs. The jobs that refugees hold are specifically vulnerable, there has been job loss across the board but refugees suffer disproportionately because the sectors in which they are employed get hit much harder than other sectors, the informal sector for example. They’ve lost their livelihood, to surge packages of support into refugees to make sure that they don’t have to take drastic measures to survive will be essential.

Here’s an example of that: in Colombia, which hosts 1.6 million migrants from Venezuela, we’ve had tens of thousands begin to return to Venezuela because they’ve lost their jobs and they can’t survive. The situation is so bad in Venezuela and so many people have left but because they can’t find any sort of employment and can no longer feed themselves or pay for a shared facility to live in they’re now going back to Venezuela.

So, cash support to refugees that have lost their jobs is essential, and then looking forward, a really big thing will be to make sure that refugees and displaced people are included in vaccines.

If you look at what’s happening with the COVID-19 therapeutic drug, Remdesivir, which does not lower the death rate but the number of days that you have to stay in intensive care, the United States has largely brought up the world’s supply and if that same dynamic plays out when we get to vaccine distribution, you’re going to have this kind of “vaccine nationalism” on the part of major wealthy countries that form alliances with big pharmaceutical companies and that is going to be where access to the vaccine happens.

The world’s most vulnerable, who can’t afford it and many times aren’t even citizens of countries, they’re going to be left behind.