As the international community marks the World Press Freedom Day at a time when ‘post-truth’ politics pervade public discourse and shape an increasingly divided political domain across the globe, one common cause united journalists from all around the world: Rally to display solidarity for their colleagues in Turkey.

The United States and the Western Europe appear to be alarmed by the emergence of “alternative facts” and the rise of right-wing populist leaders, like President Donald J. Trump at White House, who hold the very existence of media or say, truth, in disdain.

The full-fledged assault on media, which is portrayed as “the great enemy of the American people,” has sent rippling waves across mainstream media, on either side of the political divide, liberal or right alike. If ‘fake news’ constitutes the centerpiece of the public debates about media in the West, for Turkey’s beleaguered press, it is only the small part of a larger conundrum.

While the Western elites, liberals, and democrats are preoccupied with preserving the integrity of civic discourse and press freedom, the members of Turkish media are pressingly concerned over their very physical wellbeing. And they are right to do so.

Numbers speak for themselves. According to Platform for Independent Journalism (P24), 165 journalists are still in jail in Turkey. The New York City-based Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) describes Turkey as an open prison for journalists, the leading country jailed more journalists than any other country in the world. London-based Amnesty International (AI) says one-third of all imprisoned journalists in the world are in Turkey.

To address the plight of their colleagues in Turkey, journalists in Berlin, Amsterdam and other cities around the world gathered together to show support for the persecuted and jailed Turkish journalists. Amnesty International organized the worldwide events to attract attention to media crackdown in Turkey.

Amnesty Netherlands projects names of journalists jailed in #Turkey onto Embassy #FreeTurkeyMedia #worldpressfreedom https://t.co/2nzc9rXvmS

— FreeTurkeyMedia (@FreeTurkeyMedia) May 3, 2017

Free Turkey Media

In a campaign and hashtag #FreeTurkeyMedia, Amnesty International’s efforts galvanized popular support from all walks of life and all corners of the world on social media.

The campaign has attracted at least 250,000 supporters since February as people joined calls on the Turkish authorities to release jailed journalists.

“A large swath of Turkey’s independent journalists are languishing behind bars, held for months on end without trial, or facing prosecution on the basis of vague anti-terrorism laws,” AI’s Secretary General Salil Shetty said.

“Today our thoughts are with all journalists who are imprisoned or facing threats and reprisals, but our particular focus is on Turkey where free expression is being ruthlessly muzzled,” he said on Amnesty’s website. “We call on Turkey’s authorities to immediately and unconditionally release all journalists jailed simply for doing their job.”

Today on #WorldPressFreedomDay support 120+ journalists jailed in #Turkey. Take these simple steps#FreeTurkeyMedia pic.twitter.com/CUnTGd4pyK

— Amnesty International (@amnesty) May 3, 2017

According to AI, Turkey has the 1/3 of the world’s jailed journalists in 2016. More than 120 journalists remain in prison following the post-coup crackdown. At least 156 media outlets have been shut down since the coup attempt and 2,500 journalists have lost their jobs.

Only today, on World Press Freedom Day, Mehmet Gules, a DIHA reporter, was sentenced to 9 years in prison over bogus terrorism charges. A day before, a young Turkish reporter was utterly disappointed by the bewildering turn and twists of Turkey’s judicial affairs.

On Tuesday, an Ankara court ruled to release Aysenur Parildak, court reporter with now-defunct Zaman newspaper. But in a display of how judicial affairs were driven by political pressure and intervention, same judges reversed their decision, ruling to re-arrest her even before Ms. Parildak left the prison same day.

Her case sheds light on the onslaught that crippled Turkey’s media and scotches any hope for the release of any of the jailed 165 journalists.

Last month, judges decided to release 21 journalists in Istanbul. In another country, it is expected that their colleagues would exult the decision and embrace their release in joy. But in Turkey, in a sign of how Turkey’s press members fragmented over political and ideological lines, pro-government journalists launched a sweeping campaign on social media for the reversal of court ruling. Their crusade paid off as judges backed down. The government even suspended the judges who moved to release journalists.

Things have never been this difficult for Turkey’s media world. Since a failed coup last summer, more than 160 media outlets have been shuttered, thousands of journalists found themselves unemployed.

To protest the abysmal state of media in Turkey, hundreds of journalists swarmed Istanbul’s iconic Taksim Square. They displayed a robust rejection of what they say a growing homogenization of socio-political and media landscape in Turkey with the exclusion of diverse voices. The Turkish Journalists Union (TGS) initiated the protest where reporters carried banners like “Enough,” “We Won’t Remain Silent,” “Journalism Is Not A Crime,” “Free Media Cannot Be Silenced.”

In a note to underline the symbolic meaning of the day, TGS President Gokhan Durmus told media that Turkey has suffered setbacks in terms of media freedom since the day when 24 years ago today the world began to mark World Press Freedom.

He put the number of journalists behind bars as 159 and said thousands of journalists lost their jobs while hundreds faced investigations over practicing journalism.

For Mr. Durmus, the state of emergency deals a fatal blow to journalism, which faces a slow death under the restrictions and measures. The government, he noted, imposes one voice in media, wants to create a uniformed, single media structure in line with its political standing.

To the detriment of multiplicity and diversity, the media environment has become increasingly monolithic and homogenous where alternative and independent media outlets have either disappeared or shut down by authorities. The end result is a government-dictated monopoly that works hard to advance cause and agenda of the ruling party.

According to the TGS president, lengthy pre-trial detentions took the form of a punishment as journalists remain in jail for months without indictment or any charges against them. It is, he said, this kind of treatment constitutes a form of punishment itself.

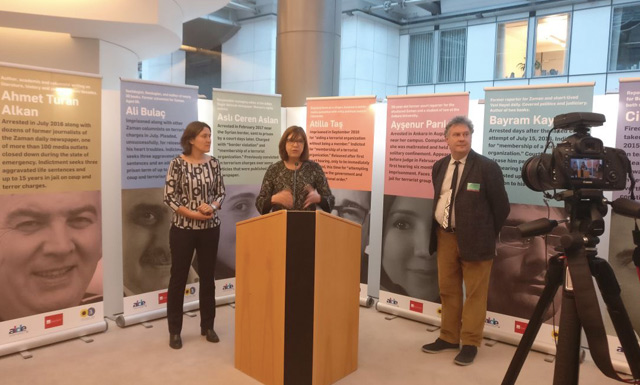

This week also witnessed an exhibition in Brussels at European Parliament to remember jailed journalists in Turkey. Titled “Expression Interrupted,” the exhibition featured photos and stories of nearly 30 journalists to represent the overall situation of all imprisoned journalists. European Union’s Turkey Rapporteur Kati Piri also was present at the event initiated by three political groups at the European Parliament.

Some of the journalists from a prison in Istanbul sent messages to a symposium held to mark the World Press Freedom Day.

“In the prison of a country whose courts have been turned into the slaughterhouse of law, I remain happy and hopeful,” P24 quoted Novelist Ahmet Altan‘s statement delivered via his lawyers.

“My trust in people and in humanity has never been shaken and never will be. Because of my trust in them, no matter what happens I will live on happily and with hope behind bars.”

His brother Mehmet Altan, a professor of political science and economics, also sent a message from the prison. “Whenever this land is not governed humanely, oppression and cruelty intensify. In the year 2017, it was our turn to fall victim to this dead-end street of despair where one follows in one’s own tracks,” P24 quoted his message.

Given that cultured people and thinkers were persecuted in Turkey’s no-so-smooth history, the past offered an abundance of cases of crackdowns on liberties. Mehmet Altan experienced that from an early age. For a man whose well-known father Cetin Altan, a veteran writer and former leftist lawmaker in 1960s, went through trials at military courts for his articles and thoughts in 1970s, there was nothing new at all.

But what jarred Mr. Altan was, as he noted, that he thought that all that was part of history that has no place in today’s Turkey, which he mistakenly believed that, left those unpleasant chapters in history.

“I used to think this was over and this ugly sense of despair would not repeat itself. I was mistaken.”

********

This article was possible thanks to your donations. Please keep supporting us here.