Warring factions in Yemen have for weeks been inches away from tearing down the historic town of Zabid, which would be another blow against Yemen’s cultural heritage – much of which has been spoilt by the war.

Zabid is a UNESCO heritage site and outdates Islam’s creation in the 7th century. Considered an “architectural jewel,” it contains the highest concentration of mosques in the country and was Yemen’s capital from the 13th to 15th century.

War 'at the gates' of Zabid @UNESCO #WorldHeritage

Architectural marvel of early #Islam in #Yemen is now under threat.https://t.co/l7cPQxJRQ2 pic.twitter.com/Ht0YDiHop5— Historic Urban Landscape (@HUL_heritage) March 6, 2018

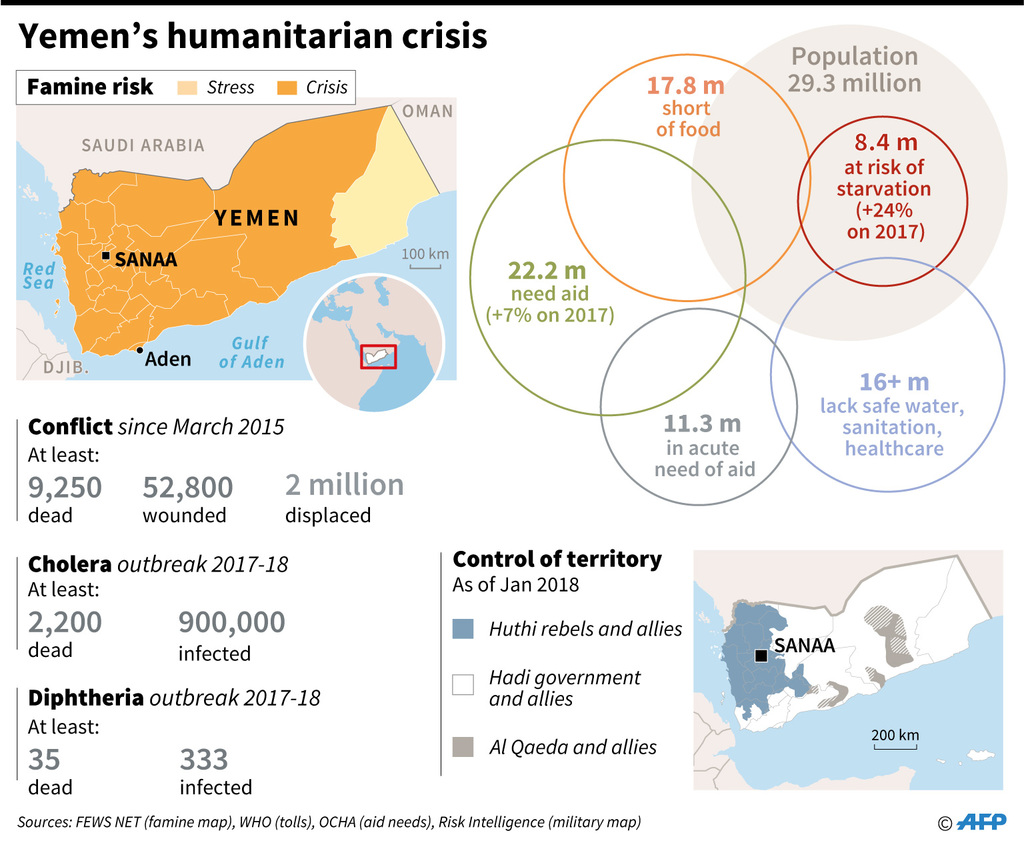

Yemen’s war has devastated the country since it began in March 2015, when the Saudi-led coalition launched a bombing campaign, reportedly to protect U.N.-recognised President Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi from opposition forces.

The operation has created what the U.N. labeled “the worst man-made humanitarian crisis in the world.” Nearly 15,000 Yemenis have died, over a million have contracted cholera and other rampant diseases, while more than three-quarters of the population need humanitarian assistance, and the country is on the brink of famine.

Not only are civilians in danger, Yemen’s rich cultural heritage is at risk of further fading away, as combatants clash near the country’s most precious artifacts.

Yemen’s claims to historic fame include being the birthplace of Arabic culture and language, one of the earliest Islamic civilizations, thought to be the birthplace of the biblical and Qu’ranic figure Queen of Sheba, among other things. Many historic monuments from these periods still remained.

According to Muhannad Al-Sayani, director of the Yemeni General Organization of Antiques and Museums (GOAM), over 78 pieces of history had been damaged or destroyed, among them are ten archaeological sites, eight museums, ten mosques, two churches, 17 tombs, and six UNESCO world heritage sites.

Fifty-nine of the sites – just over 75 percent – had been damaged by the Saudi-led coalition bombing, despite UNESCO providing a list of sites to avoid. Two of the damaged sites were hit by opposition forces, while militants like so-called Islamic State in Yemen or al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) were responsible for the rest.

As soon as the war started, so did the erasing of Yemen’s history. Saana’s historic Old City, inhabited for over 2,500 years and bearer of over 100 mosques and thousands of pre-11th-century homes, was hit by Saudi-led bombing in March, which continued for months.

The coalition claimed Houthi militias were hiding weapons in the area, after having seized the entire city before the war started. Several historic buildings were reportedly damaged. ISIS also damaged Qubbat al-Madhi, a historic mosque, in June.

Traditional architecture in #Sanaa, #Yemen. the Old City of Sanaa is a UNESCO World Heritage City. pic.twitter.com/nmvGciu8N2

— مأرب الورد (@mareb_alward) February 12, 2018

In May 2015, the historic town of Zabid already lost several historic homes from coalition bombing. The International Committee for the Red Cross (ICRC) recently warned that warring factions were inches away from further erasing the town’s heritage.

The archaeological ruins of Sirwah, which date back to the 7th Century BC and was the political and economic center of the Kingdom of Saba, was partly destroyed by coalition bombing in April and May 2015.

Another UNESCO heritage site of concern, the Great Dam of Marib, was also damaged by the Saudi-led air campaign. The largest built dam in antiquity, and in the city of Marib, the capital of the Sabaean Kingdom, it was repeatedly bombed and shows signs of damage, devastating much of the archaeological work carried out on it for the last several decades.

YEMEN – A tribesmen supporting forces loyal stands overlooking the great Dam of Marib. By Abdullah Hassan #AFP pic.twitter.com/M0WwxZijoV

— Frédérique Geffard (@fgeffardAFP) September 29, 2015

Baraqish, another archaeological city, had been repeatedly targeted throughout 2015 and 2016, with the Temple of Nakrah from the 4thcentury BC mostly destroyed by bombing. Shibam, also known as the “Manhattan of the Desert,” has faced significant damage.

Alarmed by the intense hostilities and further threats posed to Yemen’s architectural heritage, then-Director-General of UNESCO Irina Bokova announced an emergency action plan, with the hope of protecting Yemen’s crown jewels. More pledges have been made by the U.N.-body since.

While only a few factions like ISIS would deliberately target sites, the fighting can still accidentally hit historic places.

https://twitter.com/planetepics/status/964514746161561600

“Even if not targeted, historic heritage has been damaged by nearby explosions which by shaking buildings foundations provoked major cracks to their traditional structures, collapse of gypsum windows and decorations and more, and by random armed conflict,” Anna Paolini, UNESCO’s Gulf and Yemen representative, told The Globe Post.

Ms. Paolini added that, while most of Yemen’s heritage has not been destroyed, the ongoing conflict means that it is still at risk.

Like Zabid, other places can be torn down, including the city of Taiz – which has already faced some damage, and the Awwan temple, another pre-Islamic site.

Even museums like the Damar Archaeological Museum, which held over 12,500 historic artefacts, was destroyed by the bombing. Among those also damaged are the National Museum of Sana’a, the Attaq archaeological museum in Shabwa, Taiz’s archaeological museum, Qasr al-Abdali – a museum and historical monument.

“We have no news so far of archaeological sites looting but we cannot exclude it, and we monitor some of them through satellite imagery. We are also particularly worried for heritage such as manuscripts, which in Yemen are of great value, easy to smuggle and in general in high in demand on the global market,” added Ms. Paolini.

Iolanda Jacquemet of the ICRC told The Globe Post that while the conflict drags on, “it is important to remind all sides to respect international law, which demands that cultural heritage sites like those in Yemen should not be targeted. All possible precautions should be taken to avoid damaging them.”

Yemenis’ cultural heritage is a deep part of their identity, and naturally they want it preserved. Yet as the weakened Yemeni state struggles to even provide healthcare, education and security, maintaining and repairing the damage to Yemen’s history will remain a difficult task.