Control of land for crops that sustain the world’s largest food businesses, such as Ferrero and Nestle, is the driving force behind the destruction of land affecting both environment and people worldwide.

Almost a quarter of land and environmental defenders murdered in 2017 were protesting against agricultural projects. This is an increase of 100 percent from the previous year and clearly shows the growth of a new breed of a violent cartel, the agri-cartel.

An agri-cartel, any business in agriculture that has married with a corrupt entity to take land from local people, will work to bend rules and silence opposing voices in order to take land and keep it for profitable crops.

When an agri-cartel takes over a piece of land, it usually does so by stealing from a local or even indigenous people group by force. It then destroys local crops to clear land for mass-market profitable ones.

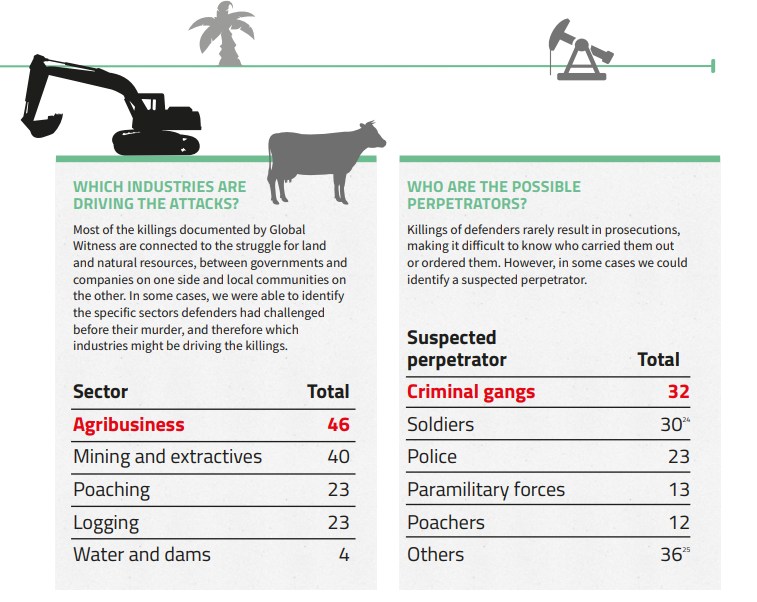

Hated by environmentalists and locals alike, agri-cartels often go unchecked by governments and are oftentimes working in collusion with them and other actors. Criminal gangs, security guards, landowners, poachers and other non-state actors were suspected of carrying out at least 90 killings last year.

In the past, such groups have been called out for noticeable atrocities, like burning rainforests down or destroying crops, but now there is data to show their abuse of human life, such as last year’s record 207 killings of environmentalists.

Agri-cartels are not one entity lead by a leader like a drug cartel. Agri-cartels can look like a lot of different groups. From a mass murder of ten people in a village called Sebu, linked to the military and Silvicultural Industries in the Philippines, to the murder of an indigenous land defender named Isidro Baldenegro linked to a drug-trafficking hitman in Mexico: agri-cartels will use any means necessary to get their land.

The five trillion dollar agribusiness sector drives much of the Western and Asian economies, and thus their need for more land, according to McKinsey. Demand for land to feed cattle, grow produce and plant palm-oil producing trees has grown significantly in recent years while the amount of arable land has shrunk by 20 percent. With a 70 percent increase in caloric demand by 2050 a possible crisis looms.

“Consumer demand is increasing for more product,” while “governments are taking the side of business and violating human rights to turn a quick profit,” Billy Kyte, Campaign Leader of Environmental and Land Defenders at Global Witness, told The Globe Post.

Juan Luis Dammert, a Program Officer at Oxfam in Peru and PhD candidate in Geography at Clark University, has been studying agribusiness and human violations in Peru for years. The economy of agri-cartels and environmental destruction is multifaceted, “but the main component is the rush for land,” Dammert told The Globe Post. There are a few elements to this.

Land Trafficking: Trade of Real Estate for Profit

First, there is land trafficking. Land trafficking is when an entity buys and sells land and uses its profits to manipulate the local real estate. According to Dammert, a rich or powerful buyer can buy a massive swath of cheap land and wait for a few years when the price goes up to sell it to an agribusiness. Often, a person in land-trafficking profits by taking land from locals and waiting, sometimes for several years, to sell it to a corporate farm. There are laws against this, but they have been proven to be difficult to enforce.

In Peru, land trafficking is a process that is growing in popularity, and it destroys the opportunity for local landowners to turn a profit when a big business comes to town, since they already sold their land when it was worth much less to an intimidating force that took it with armed power, according to Dammert.

The practice is already popular in Malaysia, a country driven by its ability to produce palm oil. Land-trafficking is a big business in itself used to drive out small shareholders of farms and usher in control of thousands of acres of land to sell for a high, manipulated price to corporate farms once they arrive needing land for their cash crops.

Land Takeover for Crops

Next, there is the taking of land by the profitable agribusiness sector.

The huge farms and ranches in South America and elsewhere that provide much of the world with its food-based products needs more land. Hostile takeover of land leads to disputes, which is what leads to deaths.

In Colombia, Hernán Bedoya was shot by a paramilitary group 14 times. He was killed after protesting against palm oil and banana plantations on land stolen from his community.

According to watchdog group Global Witness, Gamela indigenous people in Brazil were assaulted and made victims in one of the largest scale attacks in 2017. Machetes and rifles were used in an attempt to forcibly seize control of their land, leaving 22 severely injured, some with their hands cut off. Months later, nobody had faced justice for this appalling incident, reflecting a wider culture of impunity, or lack of justice, by the Brazilian government.

“One of the root causes of the problem is the imposition of projects and the acquisition of land without community consent. And until governments and companies guarantee communities a voice, this phenomenon will continue to grow,” said Kyte.

Issues with Tracking and Sustainability

Although several North American companies such as Gerber, Kellogg’s, Safeway, General Mills, Unilever, PepsiCo and Dunkin’ Donuts have received high ratings from the Union of Concerned Scientists on safe and sustainable sourcing, the agribusinesses that provide much of the world with needed food products are adept at skirting rules and working with corrupt governments to provide profits, especially to regions such as Asia that may not have ratings systems and measures for consumers to plainly see and evaluate.

In Peru, relevant governmental authorities lack the resources or the political will to verify the accuracy of studies on whether or not land is usable. These studies are often sponsored by the companies seeking land, who forge the results. Peru then grants agri-cartels land based on the flawed studies the agri-cartels produced.

According to the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), “This often results in the validation of… studies that assert primary forested land is, in fact, best suited to agricultural production, including land that had previously been classified as forestry or protected land by the government under official methodologies.”

Deceit by large companies and unwitting or even willing verification of it by governments is leading to land loss in critical areas. The Melka Group, for example, developed plantations in Peru without complying with government regulations, according to Dammert, but faced very weak sanctions.

In addition to difficulties tracking studies, companies committed to getting palm oil from lawful sources have difficulty doing so because of inefficient tracking systems and agri-cartels.

In Indonesia, Nestle said it was “committed to tackling” deforestation. A company spokeswoman said the corporation was working with partners to transform the palm oil industry “further down the supply chain” regarding oil they sourced from agri-cartels that destroyed areas of Sumatra and violated laws in order to provide it to them. Corporations with high marks for sustainability are caught between profit and policing, but seek to find ways to get the crops they need.

Shareholders, like Anholt Services based out of Connecticut, say they are “Partnering with managers to generate superior long-term returns” on their website. They have investments in palm oil plantations in Peru. They, and many other private companies with investment in South America, Africa, and Southeast Asia, are invested in land use but have no officially-backed commitment to protecting life or sacred land.

Complications with Economy and Use

Even with its corruption, agribusiness is profitable and lifts many out of poverty in many cases, according to Ec, and although land is destroyed for palm oil trees, they are the least-environmentally harmful trees for producing the oil needed to make household goods. Therefore, the answers are just as complicated as the questions regarding environmental laws and human rights.

In 2015, Singapore, which is across a sea from Sumatra, Indonesia, experienced such terrible smog from forests being burned down for land in the neighboring country that skyscrapers were blanketed in it, schools shut down and people lived on circulated air waiting for the smoke from fires to clear. This is nothing to say of those on the actual island of Sumatra working and living in the midst of it. Yet, when the E.U. reacted by banning palm oil, which is in about half of household products and foods, it came under fire for potentially destroying the livelihoods of Indonesians, where the industry provides millions of jobs to those seeking to escape poverty. The issues of poverty, commodity, and land use converge to make agri-cartels powerful.

Culture of Impunity

Culture of impunity, or exemption from punishment, contribute greatly to loss of life and land.

For example, Brazil is the country, according to Dammert, with the most land available for palm oil. It is also becoming a hotbed of agri-cartel activity and human rights violations. In 2017, fifty-seven land defenders were killed, the highest number of any country. In these killings, 25 people were mass-murdered. In one incident, around 30 police officers opened fire on a group of landless farmers in Pará state, killing 10 of them. The farmers were peacefully occupying a ranch the day before to demand that their land rights be recognized.

Brazilian President Michel Temer made it easier than ever for industries like agribusiness – associated with at least 12 murders in Brazil in 2017 according to Global Witness statistics – to impose their projects on communities without their consent and has made no efforts to reckon for the lost lives of those murdered by agri-cartels.

“There are links between organized crime and agribusiness, particularly in Mexico and Colombia,” says Kyte.

In Colombia on 30 July 2010, Jhon Jairo Palacios rang his family from Ríosucio, the capital of Chocó department, where he’d traveled by boat from his community, to tell them he would be coming home the following day. When he failed to show up, they called his mobile phone.

A man claiming to belong to a paramilitary group answered, saying: “Tell his family that he is already dead.”

According to the Global Witness report, Jhon was a member of an Afro-descendant community in the Cacarica River Basin of Chocó. Community members opposed the construction of a major road in the region – a road that would bring with it deforestation, an influx of settlers and devastation to the community’s way of life. The culture of impunity in Colombia ensured that his murder was never solved.

While reports are growing on just how many lives have been affected by this growing thuggish way of obtaining land and money, the impact of agri-cartels remains to be seen. What is happening is a social problem requiring social solutions.

Possible Solutions

Dammert said, “Land for oil palm plantations has to meet a set of requirements for the crop to grow healthily and produce yields high enough for plantations to be economically viable. Suitable areas constrain the crop’s geographies. As the industry searches for the most suitable lands, these tend to overlap with tropical forests and high conservation value areas. This is the most basic condition for oil palm’s association with deforestation.”

He argued that sustainable palm oil plantations are a real solution, but much less easy to do than clearing out a plot of indigenous land to plant a row of crops.

Kyte said solutions can start with consumers. Western consumers can call their local brands and ask if they are sustainably sourcing their food and home materials. They can also put out demands for open reporting by corporations of where they get their materials.

Next, conservation and human rights coalitions can sanction corrupt governments that work with the agri-cartels, according to Kyte. Some of this has happened in the past, but more needs to be done to curb the violence going unchecked against indigenous and local peoples. A lack of funding for indigenous peoples has caused there to be even more room for agri-cartels to take over.

According to Global Witness, in 2017, INCRA, the Brazilian state body responsible for redistributing land to small-scale farmers and Afro-descendants, saw its budget slashed by 30 percent. The budget of FUNAI, the agency responsible for protecting indigenous peoples’ rights, was almost cut in half, forcing it to close some of its regional offices in the country.

In addition, Anita Neville, vice president of corporate communications and sustainability relations at Singapore-headquartered palm oil company Golden Agri-Resources told Eco-Business that to push back against land grabbing and other social issues, there must be support for independent smallholders, who produce about 40 per cent of the world’s palm oil but often do not have access to good quality seeds, fertilizer, and knowledge about better agricultural practices.

Finally, Kyte said corporations must make a commitment to allow outside bodies to determine whether or not the land they want to use is stable and arable and allowable for crops. Kelloggs, Unilever, and others are rated highly by the Union of Concerned Scientists for sustainability, but not every company knows what to do. According to the Smithsonian, environmental NGOs ultimately hope to see oil palm growers planting on already-deforested land, rather than have them eliminate the crop and replace with another.