In the summer of 2016, the U.K. government took the unusual step of holding a referendum to determine the country’s continued membership of the European Union. Over two years since the verdict, and less than six months away from the agreed departure date of March 2019, prolonged diplomatic attempts to detach Britain from the E.U.’s extended tentacles have reached a deadlock.

There are several key reasons for this, and a principal one has been the closeness of the referendum verdict, which was almost a 50:50 split. How to make progress amidst this divisive public mood has been difficult.

Former Prime Minister David Cameron’s call to hold a referendum was influenced by rising support for the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP). This party’s growth reflected increasing numbers of the British public who wished to leave the European Union. In addition, a significant number of Cameron’s own backbench MPs wanted a referendum to engineer a departure from the transnational organization.

As a ‘remainer’ who sought to maintain Britain’s E.U. membership while pledging to reform the organization’s structure, the referendum was a strategic if risky move on Cameron’s part. If it delivered his chosen outcome, he could claim to have decisively dealt with this contentious issue.

However, Cameron miscalculated the public mood, and the country narrowly voted to leave the E.U. (52 versus 48 percent). He consequently resigned, and his successor Theresa May was promptly tasked with delivering the people’s verdict, a policy which became known as “Brexit.”

“Brexit means Brexit”

This was a challenge that would have tested any politician, and it has certainly proved to be the case. “Brexit means Brexit” became the new prime minister’s mantra, words she regularly used to win over doubters who highlighted that she too had originally been a ‘remainer.’ Yet May has struggled to match these words with appropriate actions, and as time has passed, what Brexit actually means is far from clear.

There have been various legal challenges to the referendum result, notably to how the “leave” campaign was funded, and a 2017 Supreme Court ruling declaring that the U.K. Parliament must vote on any final deal agreed between the British government and the E.U., despite May’s objections.

This in itself has created an unwelcome dilemma for the May government, principally regarding what will happen if Parliament does not support any deal eventually reached. Yet whether there is an agreed deal at all is another matter, with the prospect of a “no deal” becoming ever more likely.

No Deal Scenario

This would be an unwelcome development to both the British and the E.U. negotiators, as the consensus grows that a “no deal” scenario would have adverse economic consequences for both sides in terms of increased trading costs and in turn, inflated consumer prices.

Central to the negotiations are the single market and customs union; key mechanisms which lie at the heart of the E.U.’s structure and equate to E.U.-wide tariff-free business transactions and freedom of movement for people and goods.

The referendum outcome implied that Britain would leave both of these bodies, but how this departure can be practically delivered to everyone’s satisfaction remains unclear.

A “bespoke” deal similar to those involving Canada or Norway has been repeatedly suggested, but the precise balance of the future relationship between Britain and the E.U. cannot be agreed upon. In essence, over 40 years of European-wide integration has created a complex interlinking of institutions between Britain and the E.U., and disentangling them has proved to be very difficult.

The need for compromise is the key to any deal being agreed. Establishing a modified customs union would limit overall economic disruption, but this has raised concerns among British Eurosceptics that such continued formal connection to the E.U. would still undermine national sovereignty.

For its part, the E.U. has accused the British of “cherry-picking” the aspects of membership that it likes.

Irish Border

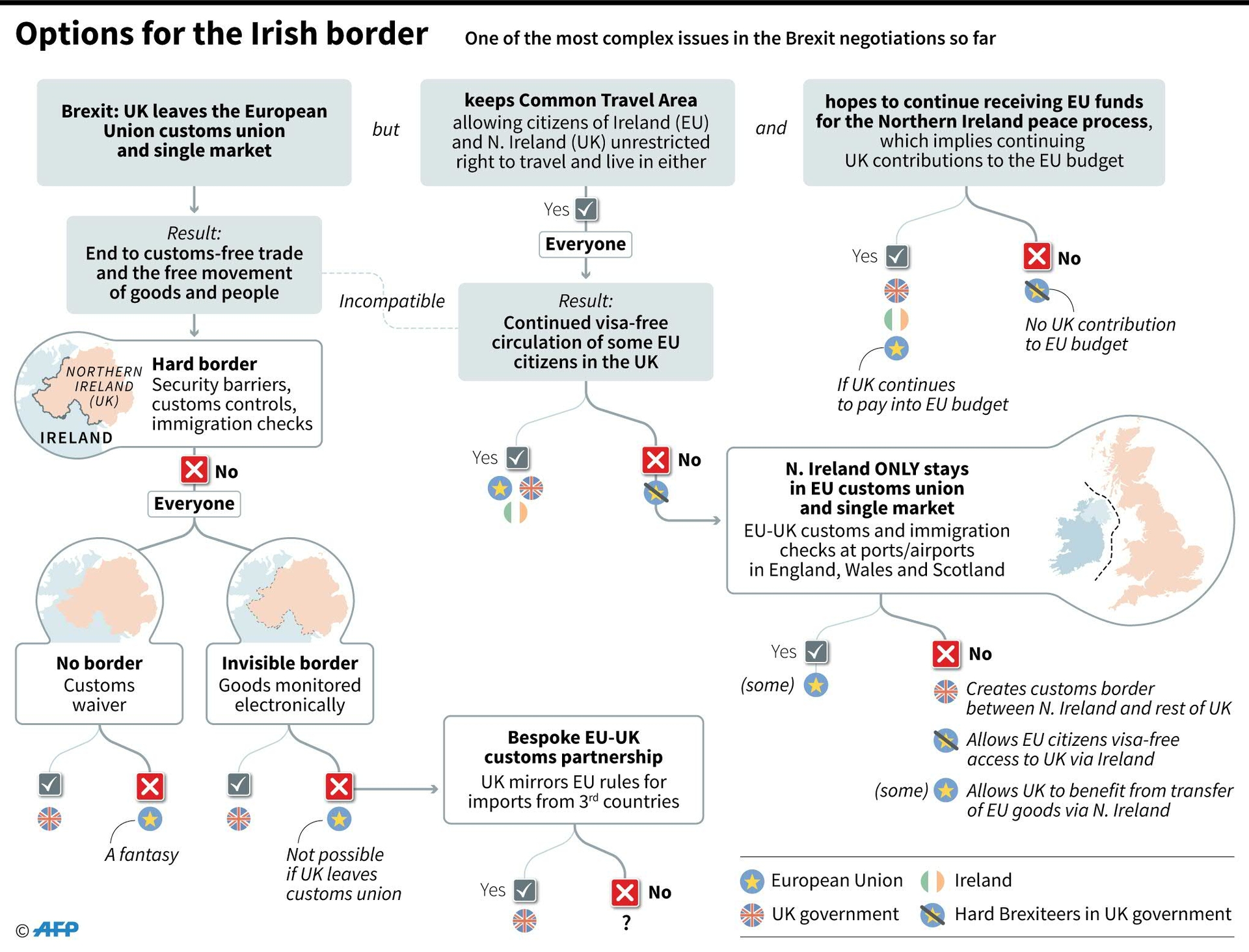

The highly complex issue of the Irish border is possibly the most problematic aspect of all. While Northern Ireland is part of the U.K. and will leave the E.U., the southern Republic of Ireland is a separate country that remains an E.U. member.

These two divided communities are plagued by a troubled history of religious violence, and the 1998 Good Friday Agreement imposed a degree of peace and a virtually “invisible border” that has been credited with stabilizing a previously dysfunctional and polarized island population.

The Brexit process threatens this stability due to its required border-checking arrangement to reflect where U.K. sovereignty ends and where the E.U.’s begins. However, a reconstituted “hard border” generates anxieties that this could re-ignite past tensions, as well as presenting renewed obstacles to trading links and cross-border population movement.

As a further complication, compromise suggestions of an alternative natural border being the Irish Sea have enraged Northern Ireland’s unionist community who view themselves as primarily British, not attached to southern Ireland. This is significant because the Democratic Unionist Party are May’s junior political partners who currently keep her in power.

Looming Departure Date

Brexit’s complexities have become more evident as the process has stutteringly developed, and the Conservative government is weakened by and hugely split over the issue.

Various dramatic implications may yet materialize, including a second referendum, a further general election or even a change of prime minister.

The issue has dominated British politics for almost three years and has generated significant divisions across political parties, communities, and even within families.

With the departure date looming, whether Brexit ultimately empowers or diminishes Britain’s global position is what all observers are waiting to see.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of The Globe Post.