Teargas against peaceful protesters, butter knives in parliament, and #FakePM hashtags on Twitter are some of the things that have characterized Sri Lanka’s politics in the past few weeks. With two men claiming to be the prime minister, recent developments in the island nation send worrying signs that its democracy is in fragile shape almost a decade after the civil war.

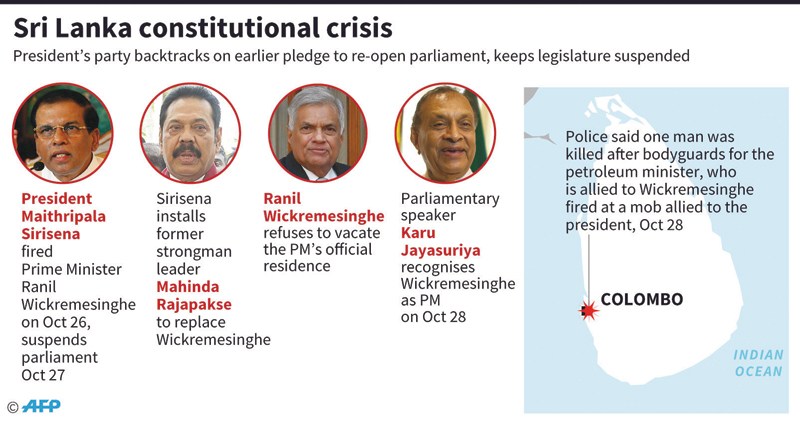

Sri Lanka’s political crisis began in late October when President Maithripala Sirisena dismissed the prime minister, attempting to replace him with the controversial former President Mahinda Rajapaksa.

Rajapaksa led the final military campaign against separatist Tamil groups that ended the 25-year long civil war fought between the separatists and the Sinhalese dominated state. In 2009, the Tamil separatists suffered their military defeat, including thousands of civilian deaths and political prisoners from amongst the Tamil minority group.

President Sirisena’s decision to dissolve parliament on November 9 is a blatant retreat from the young democracy. The president’s move comes at a surprise, given his inclusive presidential campaign back in 2015. His pro-democratic campaign revitalized new hopes amongst many who had long-abandoned trust in democracy in Sri Lanka.

As a contrast to the oppressive political climate under his predecessor, Sirisena’s presidential campaign was hailed for bridging divides by building an inter-ethnic alliance in the civil war-torn country, spanning across moderate parties, right-wing ultra-nationalists, and Tamil National Alliance (TNA), the largest Tamil political party. Telling of the hopes invested in Sirisena’s presidency is perhaps the trust he gained from many prominent civil society activists, journalists, and moderate politicians.

His engagement with the Tamil minority, whose rights have been systematically violated since independence, is particularly noteworthy. Direct violence against Tamils, not to mention other human rights violations, can be traced to at least the 1958 anti-Tamil pogrom, during which an estimated up to 1,500 Tamils were killed by Sinhalese gangs. To this day, Tamils continue to face intimidation. Most live in both militarized and underdeveloped areas in the north and east of the country.

Tamil Political Activism

Against this backdrop, since 2015, the Tamil population has displayed an increased level of civil activism, from women’s marches to commemoration ceremonies over fallen victims, to more overt protests. Particularly poignant, for more than 600 days, mothers of those who disappeared in the final stages of war have been silently protesting in northern Sri Lanka, demanding news of their loved ones.

The past few years also saw the shift in the nature of issues around which civil society mobilized and grew. Demands for transitional justice mechanisms to address past human rights abuses had largely replaced the question of how power is to be divided between minority and majority communities, which had traditionally prevailed and created much tension. This strengthening of the human rights agenda is extremely important in opposing the current threat to Sri Lanka’s democracy.

Formal Politics: TNA’s Trajectory

At the same time, the largest Tamil political party TNA has also emerged to represent a more unified and better organized political force within the formal political sphere.

Since the end of the war in 2009, the TNA managed to unify many of the previously discordant groups by moderating extremist demands, building alliances, and forging closer ties across Tamil communities in the north and east in particular. Years of such painstaking efforts by Tamil moderates have laid the groundwork for constructive discussion towards reducing the gulf between the Sinhalese and Tamil groups.

And finally, with Rajavarothiam Sampanthan, the TNA’s leader since 2001 and serving as the main opposition leader in parliament since 2015, the party secured its position as the main vehicle for Tamil interests.

This Tamil alliance, however, has not been without internal tensions and is showing signs of unraveling in light of the current crisis. A number of individuals known to have more ethnically-divisive views have left the TNA to form new political parties, including a former supreme court judge and chief minister of the Northern Provincial Council.

Polarizing speeches have the potential to derail the human rights agenda. More radical parties may now provide a formal platform for unifying those groups that too easily tap into past injustices committed against the Tamil group and shift the discussion back to the sensitive question of separatism.

Seen in this light, the president’s appointment of Rajapaksa as prime minister is all the more alarming. The government’s delay in addressing human rights abuses, accounting for political prisoners captured during the wars’ final deadly months, and locating those disappeared has already eroded people’s confidence in moderates and contributed to the TNA losing half of its voter base in the local elections earlier this year when compared to 2015.

This constitutional crisis, with the prospect of Rajapaksa’s return and the president’s willingness to bypass the constitution, may validate the rhetoric of hardliners that Tamil grievances cannot be met through political dialogue, radicalize the voter base, and further weaken Tamil trust in democratic institutions and their political representatives.

In this respect, frustrations within the TNA that the leadership could have capitalized better on the present situation and missed an opportunity to further the Tamil political agenda sends a worrying sign.

The TNA has largely driven and repeatedly emphasized that constitutional reform is the best way forward to achieve political autonomy and bring about a society where Tamils are no longer treated as second-class citizens. Weakening of the TNA, combined with present political developments, may undermine this opportunity.

Avoiding Authoritarianism

Less than two months ago at the UN General Assembly, President Sirisena called upon the international community to look at the country from a fresh perspective, as one that enjoys “sustainable peace” and seeks “national harmony and reconciliation.” Yet, the government itself has done little in terms of conflict resolution.

Instead, the most meaningful steps towards reconciliation and conflict resolution have been taken outside of formal politics by Tamil activists and by Tamil moderate parliamentarians.

The TNA, notwithstanding its weaknesses, has the opportunity to offer the most inclusive, reconciliatory, and promising vision for both the Tamil people and Sri Lanka as a whole. Whether its leaders manage to resist pressure to disintegrate and build a broad alliance with civil political activists will be decisive for the future of the Tamil communities in Sri Lanka.

The crisis calls for a broad pro-democratic front as witnessed by growing political activism that bridges ethnic and other divisions across Sri Lankan society. Perhaps the period of relative openness has provided the broad-based alliances necessary to prevent a descent into authoritarianism.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of The Globe Post.