Drama has surrounded the political developments on the Korean Peninsula. While the main attention has been given to the improving ties between the two Koreas and the lack of such development between North Korea and the U.S., the progress of South Korea’s relations with the United States has received only scant coverage.

Yet, in the shadow of world politics, surprisingly dramatic changes have taken place in that relationship. This became evident in my recent interviews with members of South Korea’s presidential cabinet, as more than one official described unwillingness of the U.S. to make compromises to “us,” referring to both Koreas.

Surely the custom has been to consider the U.S. and South Korea as negotiators on the same side, against North Korea.

Furthermore, the changing relationship between the U.S. and South Korea could be seen in the recent protests on the streets of Seoul by self-appointed “patriots” and opponents of President Moon Jae-in’s administration. According to the demonstrators, the current government is turning its back to the alliance with the United States. Despite the nationalistic passion that could be seen in the faces of the demonstrators, these patriots were carrying the flags of the United States, in addition to their national flags.

Why did these Korean patriots carry U.S. flags? And why did the South Korean officials I spoke to feel that the two Koreas were negotiating against the U.S.?

To understand how U.S.-South Korean relations are changing, it is necessary to comprehend the historical asymmetry of this relationship.

Unbalanced Relationship

After independence and the communist effort to overtake the entire Korean Peninsula, South Korea placed its armed forces under the United Nations Command (UNC). This was the command that the U.N. Security Council created before China was a permanent member of it and after the Soviet Union had temporarily left in protest.

Thus, in reality, this command is a U.S. command rather than U.N. command: it has its command structure under the U.S. military, and even its web pages are under the U.S. Forces Korea (www.usfk.mil) instead of under the un.org domain. Yet, it uses the U.N. name and authority for its operations. As much as China and Russia would like to see it removed, the United States, with its veto powers in the Security Council, still manages to keep the force alive and central to the developments in Korean Peninsula.

South Korean forces were under this de facto U.S. command until 1978. After that, the Korean forces operated under a joint Republic of Korea/U.S. Combined Forces Command (CFC), which, too, was led by a U.S. commander.

The South Korean government gained control over its forces in 1994, during the first post-Cold War peace process in Korea that produced an agreed framework between the U.S. and South Korea. This control was, however, limited as the CFC continues to have wartime control of the defense of South Korea, while the UNC controls part of the precarious ceasefire monitoring activities for South Korea.

Reducing US Role

In the current peace process between the two Koreas, the role of the UNC in the demilitarized zone, now called Joint Security Area, is being reduced by the inter-Korean military agreement.

Senior defense officials signed this agreement during a summit in September between South Korean President Moon Jae-in and North Korean leader Kim Jong-Un. The agreement enables soldiers of both countries to take command and control of security personnel stationed on the Joint Security Area between the two Koreas from the U.S.-controlled U.N. Command.

A senior presidential official characterized the agreement to me as a measure to strengthen crisis stability in the precarious process of peace negotiations. However, it naturally also changes the power relationships on the peninsula between South Korea and the United States. While the UNC yielded to this arrangement on November 6, several American security specialists in Seoul criticize the arrangement: “it is as if South Koreans would tell us to go… until they need us again,” one said to me.

The military agreement was just one of the processes where South Korea showed the U.S. that they are mature as a nation to enact sovereignty in their security affairs. While the previous efforts at the negotiation of peace have been partly controlled by powers outside the peninsula, this time the two engines of progress are both Korean.

Small Steps Towards Peace

While the United States wants to exert maximum pressures until North Korea disarms its nuclear weapons irreversibly and verifiable, the two Koreas are making small steps towards greater mutual confidence, friendship, and peace as the main aim and as an instrument of progress in disarmament. While before 2018 there were only six inter-Korean dialogue meetings on political matters, in 2018 alone there has already been seventeen!

North Korean leaders are explicit about the benefits of this strategy: they are committed to compromises with regards to their nuclear war power, but it is easier to reduce military power if an aggressive America does not acutely threaten security.

After President Donald J. Trump withdrew the United States from the 2015 Iran nuclear deal and reimposed sanctions, North Korea needs more trust on the United States as a negotiator before it is reasonable to assume major compromises on North Korea’s part.

While sanctions are preventing some of the short steps to engage and integrate North Korea into the international economic and normative system, the two Koreas have nevertheless agreed on a disease-fighting plan, while South Korea has invigorated the planning of its “northern economic cooperation.”

Peace, Dialogue, and Confidence Building

The special presidential adviser for unification, diplomacy, and national security affairs, Professor Chung-in Moon, has tested the opinions with even more radical views.

On the one hand, Professor Moon has suggested that as an independent country South Korea could lift U.S. sanctions on North Korea as a unilateral move. He has also recommended China’s president Xi Jinping to persuade the U.S. to lift some of its sanctions.

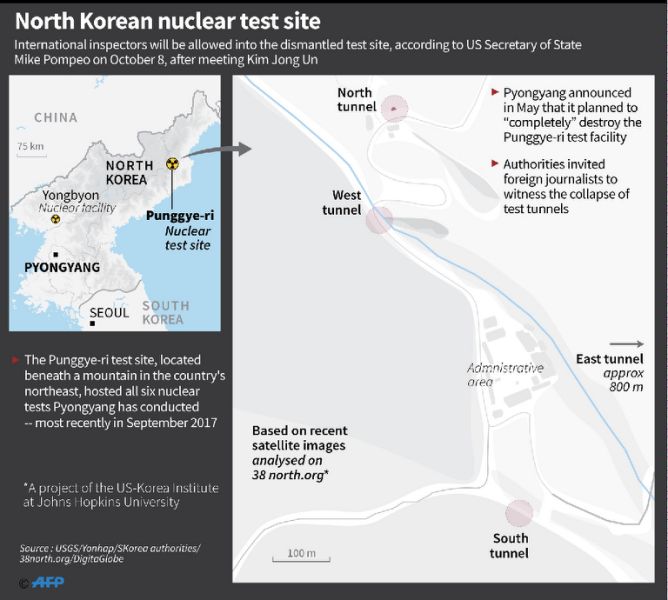

This could allow some room of maneuver for the reciprocation of North Korean compromises related to the verified destroying of its only known nuclear test site at Punggye-ri and its nuclear launch site, as well as encouraging North Korea’s moves to dismantle the Yongbyon nuclear complex that is central to fuel production for nuclear warheads.

Professor Moon keeps observers guessing whether he is talking as a representative of the government or as an individual intellectual. This makes it difficult to know how much of these statements are efforts to test reactions rather than committing the government to more radical positions.

In any case, the conservative opposition, let alone the demonstrating self-appointed “patriots,” do not share Professor Moon’s positions, as they would like South Korea to follow the American line more closely.

Yet, it is clear that South Korea is on a more independent path to peace than before. It focuses on peace, dialogue, and confidence building first and nuclear disarmament and unification of Korea only next, while the United States conditions peace to North Korean nuclear compromises and gets only limited support for that from South Korea.

South Korean activism and U.S. passivity in the peace process, together with the increasing activity of Russia and China in support of progress in the peace process rather than just in nuclear negotiations, threaten the U.S. position in the Korean Peninsula further.

The United States is needed for this peace. But will Americans participate in the shaping of the terms of that peace or will that be left to the two Koreas, China, and Russia?

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of The Globe Post.