For decades, various scholars have warned against the uncritical use of military metaphors. Susan Sontag, for instance, decried the use of the word “war,” stressing that use of military language conveys a state of exception: “In all-out war, expenditure is all-out, unprudent – war being defined as an emergency in which no sacrifice is excessive.”

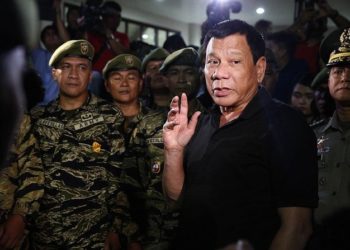

Her warning resonates in the Philippines, where people keep referring to President Rodrigo Duterte’s anti-drug campaign as a “war on drugs.” The country is not the first to call its campaign against illegal drugs a “war:” the U.S., Mexico, and Colombia all waged their own drug wars, all of which by their own admission failed.

In these instances, the conflicts were with large drug cartels run by well-armed criminal organizations, which for some may justify the use of military metaphors. Such a situation, however, is not the case in the Philippines, where the so-called drug war has targeted defenseless “suspected drug users” – or even people who have no connection to drugs at all.

Victims of Anti-Drug Campaign

Joshua Laxamana, 17, was player of the online game Dota 2 who went to Baguio City for a gaming tournament on Aug 14, 2018. He never made it back. His dead body surfaced in a hospital in another province days later. The police claim that he was a “notorious burglar” with whom they exchanged gunshots. They cited his arm tattoo as a proof – but gaming sites point out that it was actually the image of Queen of Pain, one of the characters in the game Laxamana he used to play.

Kian Delos Santos, also 17, was a student who was killed in Caloocan City, Metro Manila on Aug 16, 2017. Despite video footage showing him being dragged by police officers, the police claimed that he was a drug runner who fought back. According to eyewitnesses, his last words were “Please stop! I still have an exam tomorrow!” He was ordered by the police to run, and then was shot multiple times while running.

Joshua and Kian are just two examples of people who are the supposed belligerents of the “drug war.” A recent study of 5,000 documented killings found that victims are overwhelmingly male (94 percent) and engaged in manual labor, like tricycle drivers, street vendors, construction workers, and the unemployed.

“Most of the victims are very poor,” Professor Clarissa David of the University of the Philippines and one of the study’s lead proponents told me, adding that “23 percent of them were killed inside or right outside their homes.” Ominously, reports indicate that police officers and hired assassins are financially rewarded for these indiscriminate killings.

Meanwhile, ethnographic studies, including my own research, show that urban poor Filipinos use methamphetamine to help in their income-generating activities, giving them energy and helping them stay awake longer. Contrary to Duterte’s portrayal of all drug users as “zombies” or “subhumans,” they have diverse experiences and their drug use is best understood in their socio-economic contexts.

Duterte’s War on Drugs

In the face of this reality, referring to the anti-drug campaign as a “war” is inimical to efforts to hold Duterte accountable and convey the magnitude of the violence he has enabled at best enabled and engendered at worst.

To call it a “war” is to perpetuate a political environment that makes it less acceptable to criticize its architects. It paints a state of exception that justifies the suspension of rules of procedure, the exercise of extraordinary powers by the chief executive and his enforcers, and the use of deadly force. It boxes the population into an us-versus-them mentality, makes them think the country is under attack and must be protected at all costs, setting the stage for authoritarian rule and increasingly-brazen proposals.

To call it a “war”, moreover, is to imply that there are belligerents who actually are linked with drugs – and have the means to fight back. This is exactly what police officers say of the people, including minors, they end up killed in acknowledged police operations – nearly 5,000 of them in two years.

Inside shanties, in very poor communities where families could barely eat three times a day, men who possess at the most a gram of shabu (if indeed they were not planted evidence) are supposedly armed and dangerous. By using the term “drug war,” we play into the deadly narrative that these victims are in fact dangerous drug users and the police killed them only in self-defense.

Finally, to call it a “war” is to conjure up an image of two sides fighting each other. While there are legitimate targets for law enforcement (like drug traffickers and drug lords), and while the police have attempted to clean their ranks, these have been overshadowed by the death toll of mere users or small-time dealers that increases by the day, and by the use of drug-related accusations to stifle political dissent.

In a sliver of hope, the policemen who killed Kian Delos Santos were recently convicted of murder and sentenced to life imprisonment – but justice remains elusive for Joshua Laxamana and many others.

No Real War

There aren’t two sides to the tens of thousands of killings in the Philippines. There is only the state making lists, threatening the poor, and declaring the number of people killed as an “accomplishment.” There is no real war.

When a conflict is called a war it becomes unpatriotic to be against it. When something is called a war it becomes acceptable to have “collateral damage” or “casualties,” even when they are children caught in the crossfire, or worse, children targeted by the police.

What’s happening in the country, then, can only be called a massacre – or a “state-sanctioned killing spree.” Calling it out for what it is will not stop Duterte, but it will call attention to what is truly at stake in the Philippines.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of The Globe Post.