Eva Golinger is an American attorney and journalist who was a legal advisor to former Venezuelan president Hugo Chavez. She’s also the author of the best-selling book, “Confidante of ‘Tyrants:’ The Story of the American Woman Trusted by the U.S.’s Biggest Enemies,” which documents her political work in Venezuela and her rise into the close circle of the country’s late president.

“I had breakfast with Hugo Chavez, lunch with Bashar al Assad, cocktails with Putin and dinner with Gaddafi. Fidel Castro sent me flowers, perfume and cigars. Ahmadinejad told me he loved me. Chavez proclaimed me his defender,” she writes.

On Wednesday, Golinger sat down with The Globe Post to discuss the unraveling political crisis in Venezuela and the Trump administration’s efforts to overthrow the government of Nicolas Maduro.

Q. Of course, a dramatic political crisis is continuing to unfold in in Venezuela this week. But to start, I actually want to take a step back and sort of set the stage for those who may not know a whole lot about Latin America. On Monday, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo was at the United Nations trying to drum up support for recognizing the opposition government in Venezuela. He spoke a lot about freedom and democracy, but sitting sort of ominously behind him was Elliot Abrams, whose been appointed as the special envoy to Venezuela. For those who don’t know, who is Abrams and what does his appointment tell us about the current U.S. policy and the context from which we should view it?

Q. Golinger: Certainly the naming of Elliot Abrams was a rather shocking development for those of us who have been deeply involved also, particularly in Venezuela, but in Latin America for years. He’s notoriously known for his work facilitating the arming of the Contras in Nicaragua during the “dirty wars” in the 1980’s as well as arming other death squads and right-wing paramilitary forces throughout really the region of Central America in Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador that caused the deaths of tens of thousands of people. Mass slaughter, mass grave sites, torture – this is something that Elliot Abrams has justified as part of a Cold War battle. He’s adamantly anticommunist and is still caught up in that mindset and was actually convicted of, I believe it was two counts of lying, perjury, to Congress specifically about his role and the U.S. government’s role in the illegal arming of these paramilitary forces that directly assassinated thousands of innocent people in Central America in the 1980’s.

And subsequently, he’s one of the sort of stalwart Neocons in Washington. He worked in the Reagan administration and was brought back during George W. Bush. He actually played a key role overseeing the 2002 coup d’etat against Hugo Chavez who was president of Venezuela. It was a coup backed by the United States, not as overtly as what we are experiencing now with this current regime change operation. But the naming of Elliot Abrams has conjured up a really dark history of the United States intervening in Latin America through violence, through death, through political assassinations that resulted in the instability and chaos and insecurity and levels of violence in Central America that have carried through to today precisely to this immigration crisis that’s affecting the United States today. We can trace that directly back to Elliott Abrams and the role that he played in destabilizing the region. So clearly, that is of extreme concern to see that he’s now been named as a key player in the current situation in Venezuela. It’s become clear to someone like me who’s analyzed and researched U.S. policy towards Venezuela for almost 20 years that this is clearly escalating at a rapid pace and it seems to be that the mind is made up on the part of the Trump administration and that they’re all in for regime change

Q. In terms of the patterns of which countries we have chosen to try to bring about regime change in historically throughout Latin America, what kinds of governments are generally considered sort of unacceptable to the United States? Is it just sort of countries that seek some form of independent development? Is it any leftist governments in general? Obviously, back when Abrams was doing his work in the Reagan Administration this was sort of in the context of the Cold War, but it wasn’t exactly strictly Communists that we were going after was it?

Golinger: Well, also there’s geostrategic interests. Of course, in a particular case during the Cold War, it was a question not of the ideological differences. I think that might play role but it’s more of a minor role compared to power and influence and dominance in this region which the United States continues to see as its backyard and it’s zone of influence. So clearly having, in that time period, the Soviet Union gaining influence in this region was a direct threat to U.S. control and power over its own hemisphere just as Russia today sees the United States involvement either in Ukraine or the expansion of NATO to the Russian borders as a threat to its zone or sphere of influence. That’s just geopolitics.

But clearly the United States has a double standard when it comes to what government it chooses to support. There have been many statements coming out publicly from the Trump administration talking about the need for change in Venezuela, talking about freedom and human rights, for democracy. But the actual truth behind that is that Venezuela has the largest oil reserves on the planet. And yes, while it’s true that the U.S. has further developed oil production in the United States, it’s not going to last forever. I’ve been seeing that argument passed around by a lot of analysts in the mainstream media, than “no, this is not about oil because the U.S. is now major oil producer.” But if you look in terms of reserves – we’re talking long-term – Venezuela has the largest in the world which means that it will last longer and will be used to explain for many other purposes. And it’s not just oil, it’s heavy minerals, it’s gold, and it’s a geo-strategic position. Venezuela is the port of South America. There’s a variety of reasons. But it in any case, we’ve had [National Security Advisor] John Bolton coming out publicly on Fox News straight and direct saying this will benefit U.S. consumers, this will United States companies and jobs in the United States to have control over Venezuela’s oil industry.

Q. If [U.S.-recognized interim President Juan] Guaido is able to succeed and rise to power, hypothetically, to what extent do you think he’ll pursuit an agenda of privatization that will allow American investors and other multinational actors to sort of extract wealth and resources out of Venezuela? Have there been signals from the U.S.-backed opposition that is what they intend to do?

Golinger: I assume that that would be immediate. Now, they have not put out yet an actual platform of what is there agenda going to be. But we know from the past really what it is and there have been conversations ongoing. This would not be happening with U.S. backing if the U.S. did not have a guaranteed inroad into Venezuela’s oil industries. You know, I just want to point out that Venezuela has remained in trade with the United States. The United States continues to be Venezuela’s largest customer in terms of its oil production and of course Venezuela owns Citgo which is a major gas corporation in the United States and has also had stake over the years in several refineries that are located within the United States. Some of that has changed over the past decade. Venezuela has sold off a lot of their shares.

The point is just that there’s no question that the opposition, if they get into power Venezuela. they will roll back many of the reforms that have taken place over the years during first the administration of Hugo Chavez and then carried on during the Maduro because frankly he hasn’t made any major policy decisions since he has been in power in terms of affecting that kind of foreign commerce or industry. But oil was nationalized in Venezuela in 1976. This isn’t something new. This was not something that was done under Chavez or socialism. However, by the 1990’s, the oil company owned by Venezuela, the state-owned company Pedevesa, was functioning practically like a private corporation benefiting the elite in power as well as the high-level oil industry executives.

“The naming of Elliot Abrams has conjured up a really dark history of the United States intervening in Latin America through violence, through death, through political assassinations.”

But at the same time, the foreign companies that were heavily invested in Venezuela’s oil industry, primarily U.S. based ones like Exxon, Chevron, and others, were not subject to the rules and laws that were in place in Venezuela throughout those years. For example, they weren’t paying royalties, they weren’t paying taxes. There were lots of commissions that were given to state officials. There was corruption and also in general, Venezuela wasn’t profiting as much as it should have been from those relationships. So when Chavez was elected in 1998, Pedevesa was on the verge of being privatized. That’s what was going on, and poverty had grown to nearly 80 percent in the country. So one of his main goals was to sort of take control again over the oil industry. It wasn’t to nationalize it because it was already nationalized, just to ensure it wouldn’t be privatized.

Q. You mentioned in a recent interview on the Majority Report that Maduro has not been able to garner the same level of support that Hugo Chavez did from the traditional base of the Bolivarian movement. To you, what do you think have been Maduro’s biggest failures and as someone who knew Chavez personally, what do you think he would think about Maduro and the current situation?

Golinger: No one could have filled Chavez’s shoes and his death was not anticipated. That’s also one of my critiques of – as much as I appreciated so many of his achievements in the country, primarily reducing poverty dramatically, redistributing the nation’s oil wealth as it should have been and overall improving the quality of life of most Venezuelans and ensuring universal access to healthcare and education – all of those were very admirable achievements. But at the same time, he became entrenched in power the longer he stayed in power. And while that may never have been an initial objective, that became a reality. The movement became focused around one person as though he were the only enabler of it and guarantor of its success. That in itself became problematic, especially when he unexpectedly fell ill with a terminal disease with a very aggressive form of cancer and there had been no preparations made for a successor.

So when it came time to make that decision, he had a small pool to choose from and Maduro was one of them. The truth is I’ve known Nicolas Maduro for many many years – well over a decade – and he is someone who has risen through the ranks of Chavismo, who began, even though he came from a humble background as a bus driver, very much connected with those deep workers rights and the union rights roots, grassroots movements. He was very connected in that sense to communities, which is the fundamental support system of the Bolivarian revolution in Venezuela. And then he became a deputy and a legislator in the National Assembly, president of the National Assembly – the roll currently of Juan Guaido – and subsequently foreign minister for six years. So he was one of the more experienced and likable members and he was the one that Chavez eventually selected to be his successor. He wasn’t as charismatic or likable and certainly wasn’t as prepared. He always saw himself as more of one of Chavez’s soldiers rather than a leader himself of the country. He didn’t aspire to be president and wasn’t prepared.

“I’ve been very shocked to see dramatic changes in [Maduro’s] way of governing … declaring anyone who dares to criticize him or his government as traitors, myself for example.”

Also, part of that is he is heavily influenced by circle of advisors around him, amongst them his wife, who is a very powerful figure in the government party and who also has links to a lot of corruption and illicit activity networks throughout the country, including white-collar crime but also extortion and things that are highly problematic, especially for the first lady of the country. At the same time, there are also a lot of other advisors around him that influences his decision-making. Initially, there were some that were more experienced but that’s been weeded out as his paranoia has grown because of the increasing threats around him. And the key sort of ring around him has been tightened and been reduced in terms of people who have direct access an influence over his decision-making.

My point in explaining that is just to say that he’s someone who sort of fell into this role, wasn’t prepared for it and is heavily influenced by others who don’t have the best of intentions for the nation and are involved in undesirable activities that have a very dangerous impact on the country. But he still is someone who has always been committed to the overall vision of social justice and fundamental participatory democracy of the Chavez lead Bolivarian revolution.

That said, I’ve been very shocked to see dramatic changes in his way of governing – more authoritarian tendencies, willingness entirely for any kind of criticism, even constructive criticism in the movement, declaring anyone who dares to criticize him or his government as traitors, myself for example. And also making these very impulsive, erratic decisions about the economy, surrounding himself with a circle of economic advisers who really didn’t have proper experience for that role and completely devastated Venezuela’s economy. That was obviously combined with crippling sanctions imposed by the United States, but still I would lay more of the responsibility for the economic crisis on Nicolas Maduro’s mismanagement of the Venezuelan economy.

Q. And just to be clear, even for the people who supported Chavez but are unhappy with Maduro for all of the reasons you just outlined, it’s not like all of these people are necessarily supporters of Guaido and the US-backed opposition, right?

Golinger: Not at all. In fact, I would say there’s probably, as there’s always been, about 30 percent hardcore support on both sides, for Maduro as well as for the opposition. And the in-between goes back and forth. The majority of Venezuelans, in my opinion, would oppose any kind of foreign intervention in their country and would not want to see a right-wing, elitist government come back into power. However, they want the country to get better. They want things to improve and they don’t necessarily like Maduro. In between that there are many who continue to support Maduro because he’s seen as the bearer of Chavez’s legacy.

At the same time, I do believe that many would prefer an alternative. The main problems has been that there have been leaderships that have begun to grow from within the movement of Chavismo but they been crushed by Maduro, by his supporters and his party, and either declared as treasonous or otherwise neutralized. Many of them have been harassed or been arrested. Some of the more prominent leaders like Miguel Rodríguez Torres, who was building a movement and was planning on a presidential run has now been in prison for almost two years based on bogus, trumped-up charges of being a CIA agent. So that’s generally part of the problem. While there are many who do not support the opposition and oppose absolutely the regime change operation in place and would not like to see Juan Guaido as their president, they don’t have an alternative and so they stick by Maduro, even though they would rather see a change in the country in terms of the leadership.

Q. Getting back to the sort of day-today economic misery that ordinary Venezuelans have had to endure in recent years, even with all of Maduro’s failures, as you mentioned, U.S. sanctions have also obviously taken a really serious toll on the economy. Before the coup in Chile that brought [Augusto] Pinochet to power, Henry Kissinger famously said the US was going to “make the economy scream.” Considering how reliant Venezuela is on its oil exports, what kind of a toll do you think the new U.S. sanctions are going to have on poor, ordinary Venezuelans who are of already struggling mightily?

Golinger: These sanctions – the latest round – will have a crippling effect on the economy, precisely because the U.S. has taken control of Venezuela’s assets, over seven billion [dollars] in U.S. banks and financial institutions. And at the same time in the United Kingdom, they refused to turn over 1.2 billion [dollars] in Venezuela’s gold. So there are severe economic impacts on Venezuela from this latest round and on top of just the seizing or the freezing of the assets in those countries, of course the U.S .has imposed what is essentially a ban on exporting oil from Venezuela to the United States.

“They’re naively believing somehow that U.S. Military operations would only target the government … that’s not how it works. If they bomb an area of Venezuela, there will be all kinds of classes and colors of Venezuelans who will be killed.”

However, it’s still unclear how that’s going to play out because Chevron happens to be one of the major investors in Venezuela and trade partner. So I believe there’s some kind of exception for Chevron at this time. Although it seems to be that if there’s any oil that are already en route that belongs to Chevron from Venezuela, that will proceed but future shipments will not. Venezuela responded swiftly by saying you have to prepay for everything before we ship anything out of the country. But still, they’ll suffer. Because while Venezuela has diversify their trade, largely the oil that is going to Russia, to China and to Cuba, for example, of Caribbean Nations that received Venezuela’s oil, it’s not being paid for in liquid dollars or cash. It’s either repayments for loans that have been made to Venezuela or its being paid in-kind in services. For example, in Cuba they pay services of doctors that provide healthcare to Venezuelan citizens.

So Venezuela will suffer greatly. These sanctions are different from ones that have been imposed before by the United States. There’s been rounds of sanctions since 2006, increasing under Obama in 2009. But those were targeted against individuals, mainly in the government and ex-government officials. However they’ve still had an impact on the economy because they’ve targeted individuals who run Venezuela’s financial institutions who are therefore prohibited engaging in any kinds of transactions with anyone in the U.S. So for example, if the person overseeing Venezuela’s Central Bank is sanctioned by the U.S., then there can be no dealings with any U.S. entities or individuals with that person who runs the Central Bank.

That means essentially there can be no dealings, no transactions with the bank itself because the person who signs off on it is sanctioned by the United States. So a lot of times the opposition in Venezuela and others in the mainstream media have tried to say, “well these are targeted sanctions, they don’t affect the majority of Venezuelans.” Well that’s not true. So when it comes for example to food products or other commercial products that Venezuela has had a shortage of over the last few years, while yes a large part of that is due to mismanagement, to corruption, to fraudulent trade deals that some of made that they profited off of, at the same time it’s also due to the fact that they can’t engage in a lot of transactions with companies from the United States. For example, because of the fact that the individuals who are running the institutions that oversee those transactions are sanctioned by the U.S.

So it’s had an impact on ordinary Venezuelans lives before and now will be much worse. We’ll see – the currency is already practically worthless. Increasingly, it’s more difficult to access to basic consumer products such as food and medicines. The healthcare system has deteriorated dramatically in the country, and that’s why we’re seeing millions of Venezuelans leaving the country and migrating, mainly out of the economic crisis and a need for opportunity.

Q. Is there any indication that the increased economic pressure from the US will do anything to sort of tip the scales in terms of influencing the military leadership into abandoning Maduro? Or do you think it will be more of just sort of increasing the misery of ordinary Venezuelans without actually changing the political dynamics?

Golinger: I think it will have an effect on both. I think that it will impact the military because of the fact that many of the government institutions in the country are run by the military, even those that what would traditionally not be. Chavez began this process of putting generals in charge of Ministries and Maduro has increased that because he himself is not from the military like Chavez was so he doesn’t command that respect sort of innately. So he’s provided incentives to sort of stand by him essentially and now even more so. So it will have a direct impact on them because it will reduce, of course, the economic gain that they have been taking in running those institutions and it will affect the lower and middle ranks because everybody’s purchasing power will decrease there will be limited access.

That type of impact effects everybody. The military, the soldiers are impacted and their families as much as ordinary, civilian Venezuelans. At the same time, there has been a shift in Venezuela’s military doctrine over the last decade away from U.S. ideology in terms of militarism. It’s more focused on a Latin American Doctrine and they see the United States as an adversary and are looking more towards defending the sovereignty of their territory. They have over half a million members of their armed forces and they have a civilian reserve that’s nearing what the goal is of two million by April. But it’s already over 1.2 million. They’ve announced the creation of 50,000 battalions nationwide in communities of just civilians. But many of those groups have access to weaponry as well and the armed forces have advanced weaponry primarily purchase from Russia over the last few years after sanctions were imposed in 2006 that prohibited Venezuela purchasing any defense equipment from the United States.

So that’s why they turned to Russia initially and that relationship became expanded in all areas. In any case, the point is just that there would be resistance from the military on a sort of ideological basis to any kind of foreign intervention. However, there will be erosion because of the economic sanctions that will cripple Venezuela’s economy and ramp up the pressure on Maduro and could potentially weaken military support around him.

“I still believe that that is the role of the International Community – to encourage and to facilitate a dialogue. That is the only way out Venezuela’s conflict that will be resolved without war.”

But there’s no guarantee of that and if the opposition is unable to maintain the momentum of their supporters, then the government will clearly see their weakening and will take advantage of that. Because that is how it’s played out in the past. This is not the first time this has happened. It may seem that way to the media in the U.S. but in Venezuela this happens practically every year where the opposition violently protests in the streets with the goal of ousting the government. Generally, they go on for a few weeks and then lose momentum and die down and then are divided amongst themselves. This is the first time you’ve seen a rallying sort of figurehead like Juan Guaido in a few years for the opposition and receiving such a explicit and very firm support from the Trump Administration and from Trump himself and then from European nations and nations in Latin America as well, which would certainly make this a different scenario. I don’t doubt that whatsoever.

I do believe that the opposition is not going to back down and that the Trump administration made up their mind that this is a regime change operation and are committed to see it through and that the opposition is emboldened not to back down. Maduro may be indicating he may be willing to negotiate. But they’re not negotiating to give up power, they’re negotiating possibly to share power but not to give it up. I don’t foresee that that would be acceptable in terms of the current posturing by the opposition backed by the Trump Administration.

Q. The other day, John Bolton, in a pretty bizarre way, exposed that the U.S. intends to send 5,000 troops to Columbia. He was in the White House briefing room and allowed his notepad to be exposed and photographed with a full line saying “five thousand troops to Columbia.” If the United States did intervene militarily down the road, what might something like that look like? And what kind of consequences would that have for the country and for the region as whole?

Golinger: I do believe that that plan is in the works. It’s not a new plan. The U.S. has been drawing up contingency plans for military operations in Venezuela as well as other countries where they have strategic interests. The U.S. has a military presence in Columbia, which is pretty significant. Columbia has a very porous border on the western side of the Venezuela. Of course, the U.S. has a military presence in the Caribbean, 50 km off of Venezuela’s northern Caribbean coast in Aruba and Curacao. Venezuela has maritime territory which reaches out to Puerto Rico. The U.S. is always concerned about the influence of countries like Russia and China or Iran in the hemisphere that is so close to U.S. territory.

Of course, we have a newly solidifying relationship militarily with the United States and a new right-wing government in Brazil. I think that the the troops to Columbia – whether or not that’s true or whether it’s just a confirmation of troops that are already there, which could be the other case – that they already have special forces that are on the ground in Columbia. There have been plans drawn out recently, they have bases that monitor and surveil all the happenings in Venezuela.

I think that the danger is that they’re under-estimating the reaction of Venezuelans. If they think they’re just going to kneel down and surrender and wave the white flag, that’s not going to happen. There’s too much at stake for the people in power in Venezuela to just leave with no resistance. There will be many in the country, millions, who would die to defend their nation. So I think that we would see a violent confrontation. There’s been other military interventions where the U.S. thought it would be clean and simple like Panama or those in Central America or more recently – look at Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, Libya – they end up creating way more chaos and suffering than what was initially taking place in those countries

Q. And for the region as a whole, I mean obviously there is already a migration crisis. Do you think it would exacerbate that as well?

Golinger: Well, surely there would be people fleeing the country if there were to be any sort of U.S. military intervention. I think those who are clamoring for that kind of intervention – there are Venezuelans clamoring for that. They may not live there necessarily. It may be largely the expat community in the United States, principally. They’re naively believing somehow that U.S. Military operations would only target the government and the government supporters. But that’s not how it works. If they bomb an area of Venezuela, there will be all kinds of classes and colors of Venezuelans who will be killed. Who will be mained. Who will suffer. So I think people need to really consider what kind of action they’re advocating for when it comes to regime change in Venezuela. It’s very difficult to imagine at this stage a negotiated settlement that would be peaceful. But I still believe that that is the role of the International Community – to encourage and to facilitate a dialogue. That is the only way out Venezuela’s conflict that will be resolved without war.

More on the Subject

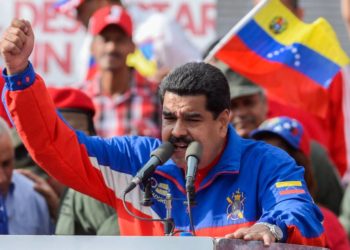

Venezuela’s President Nicolas Maduro said he was prepared to hold negotiations with the U.S.-backed opposition and added he would support early parliamentary elections, Russian news agency RIA Novosti reported on Wednesday.

Maduro Ready for Talks With Opposition, Early Parliamentary Polls in Venezuela