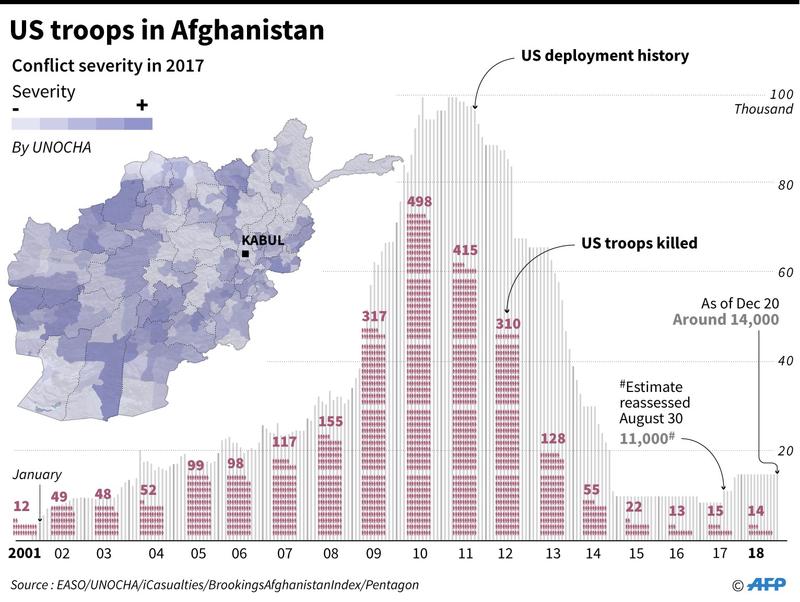

As the “forever war” drags on into its 18th year, critics on both sides have pointed to the lack of objective rationale for remaining in Afghanistan. Fiscally-minded observers have balked at the trillion-dollar cost of sustaining – as Lieutenant-General Kenneth F. McKenzie recently noted to Congress – what has essentially turned into a geopolitical stalemate. Humanitarian objectors such as philosopher Noam Chomsky, on the other hand, have pointed to the atrocious death tolls on military personnel, local civilians, and outside contractors.

Although the short-term stabilizing effects of the American presence in Afghanistan are irrefutable, successive U.S. administrations have recognized that they cannot afford to be the glue holding Afghanistan together forever.

In fact, the one point on which parties to the Moscow negotiations seem to be able to find common ground is that an eventual withdrawal is in the interests of all stakeholders to the conflict. With a recent BBC study showing the Taliban insurgency to exert full political control over 14 districts within the country (as well as being “openly active” in a further 263) this is hindered by fears of creating a post-withdrawal “power vacuum,” which, rightly enough, seem to be grounded in empirical evidence.

Democratic Representative Barbara Lee’s comments in 2001 – as she stood as the lone voice to oppose the war in either the House of Representatives or the Senate – appear particularly prescient in such a context. Lee warned against embarking on an “open-ended war with neither an exit strategy nor a focused target” – exactly the war Lieutenant-General McKenzie described in his appearance before the congressional hearing in December.

Timeline for Withdrawal

On Wednesday in Moscow, Taliban leader Abdul Salam Hafani suggested that U.S. leadership had repeatedly communicated an intention to withdraw 50 percent of its troops by May 1; comments which were swiftly rejected by the Pentagon.

Though admirable in theory, the refusal to publicly commit to a unilateral timeline for withdrawal at the widely-publicized Moscow negotiations could actually serve to undermine U.S. interests in the region and is indicative of a broader trend of Western ignorance of the nation’s complex geopolitical structure. For example, while the U.S.-backed Mohammad Ashraf Ghani administration has so far boycotted the talks in the Russian capital, they have shown themselves to be more than capable of cooperating in sparsely-populated, Pashtun-majority areas of the country held under Taliban occupation.

Writing in Foreign Policy, academic Ashley Jackson points to Helmand province as an example of participatory governance – an area in which it is not uncommon for representatives of the government in Kabul to sign memorandums of understanding with local Taliban leaders, sharing responsibilities for service provision. She notes that in some areas, the insurgency is responsible for ensuring the security of schoolchildren and staff members, while the provincial representatives of the official government provide the funding for the education system itself.

While it would be remiss to suggest that the Taliban should play any role whatsoever in the school system (at least in an ideal world) given their track record in women’s educational rights, the cost of continuing this military adventurism may just be American strategic primacy in other key regions of the world.

US Should Refocus Priorities

Although not necessarily a reference to Barack Obama‘s “Asian pivot,” the fact remains that the trillions spent in Iraq and Afghanistan would have been better directed towards ensuring the growth of China is couched in a robust diplomatic relationship, or on playing a pivotal role in brokering the difficult Japanese-Korean relationship.

Moreover, these resources could have been spent on intelligence-gathering in Syria to understand (and make appropriate preparations for) escalating tensions between Israel and Iran, or even to combat the globally existential threat of climate change. None of these strategic goals – all of which have the U.S. can be said to have a direct and enduring interest in accomplishing – can be said to cost anywhere near the most conservative gross estimates of Middle Eastern intervention, and yet they remain relatively neglected.

Does the USA want to be the Policeman of the Middle East, getting NOTHING but spending precious lives and trillions of dollars protecting others who, in almost all cases, do not appreciate what we are doing? Do we want to be there forever? Time for others to finally fight…..

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) December 20, 2018

Whether or not one happens to view U.S. primacy as an inherently good or a bad thing, it seems that the continued sustainability of the doctrine depends upon America’s willingness to refocus and prioritize; directing a notably shrinking pool of influence towards a proportionately smaller number of geopolitically strategic goals.

Although most pundits predict violence in Afghanistan to increase in intensity after a U.S. departure, a declared timeline would ratchet up pressure on Kabul to take a conciliatory approach with their insurgent counterparts.

Far from an optimum (or even guaranteed) solution, this has proven to work in some of Afghanistan’s most embattled provinces. In fact, it might just be the only way to shore up the vacuum to come.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of The Globe Post.