Growing up stateless means facing the world as an outsider; it means having no birth certificate or nationality to one’s name.

More than 2,000 new children were registered as stateless in Europe last year, and with limited access to virtually all social services and education opportunities, their life trajectory in 2019 remains bleak.

The U.N. Refugee Agency (UNHCR) and the U.N. Children’s Fund (UNICEF) have called upon European leaders to turn their attention towards mitigating this phenomenon, which is now estimated to affect half a million children across Europe.

Under Article 1 of the 1954 U.N. Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons, a “stateless person” is not considered a citizen by any state under its laws. Children are particularly affected due to joint factors of rising birth rates across Europe and the often inherited stateless designation at birth.

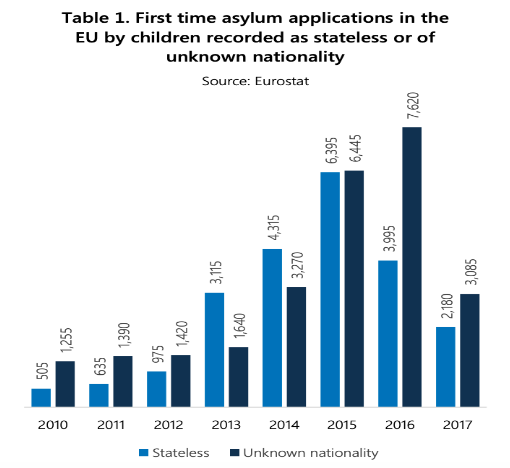

Within the last year alone, over 2,100 new children were registered as stateless in Europe, a four-fold increase since 2010.

With both migration levels and stateless persons identified in Europe peaking between 2016 and 2017, the links between higher migration levels and statelessness cannot be understated.

Yet statelessness remains largely an invisible problem due to limited awareness of the experience itself and the complicated nature of fixing a cross-border problem. Looking into the current climate of statelessness, UNHCR and UNICEF have released a 2019 Advocacy Brief examining the causes, compounding factors, and possible solutions needed to address childhood statelessness.

How Children Become Stateless

Discrimination on the basis of minority status remains a fundamental aspect of statelessness determinations.

Lack of birth registration is also a major determinant, disproportionately affecting families living in poverty and more informal settings outside of major city centers.

Parents may refrain from acquiring birth certificates for their children due to possible fear of arrest, detainment, or even deportation. Without a birth certificate, many children of refugees may inherit their parent’s statelessness — perpetuating the vicious cycle from one generation to the next.

For parents that do decide to seek birth certificates for their children, gaps in nationality laws and gender-based discrimination may further hinder grants of nationality.

Lacking documentation of both birth parents and the location of a child’s place of birth, states may refuse to grant a birth certificate — and thereby deem the unprotected child stateless.

Only 17 of the 51 European states now automatically require nationality to be granted to otherwise stateless children, and only 12 European countries of arrival have legal procedures in place to reduce statelessness determinations at the outset.

Under the current landscape, more stringent enforcement mechanisms are being urged to accompany top-down measures such as legal safeguards.

According to the UNHCR Report, while some state laws now permit grants of nationality, in many instances local border authorities still discriminate on the basis of minority status and fail to issue birth certificates.

European Roma Rights Center President “Ðorđe Jovanović, said the Roma, specifically, are “without a doubt the most over-represented ethnic group in Europe by numbers of stateless children” and continue to face both cultural and legal persecution.

The UNHRC Brief also cites the Roma as a group particularly affected by childhood statelessness.

The dissolution of former states, lack of formal procedures, and a continued lack of enforcement of international law have all contributed to the proliferation of statelessness in Europe within the past few years.

Lasting Consequences

Without a birth certificate and legal identity, stateless children face burdensome challenges to everyday life.

They are denied access to both socioeconomic rights such as education, healthcare, and employment opportunities and civil rights such as freedom from arbitrary detention and political participation.

Stateless children also face social marginalization among peers and are more vulnerable to stigma and abuse due to a lack of legal protections. Growing up as an outsider from birth can have very serious psychological ramifications.

If you were invisible, what would you do?

2,100 children were registered as ‘stateless’ in Europe last year, our new report shows.

Everyone has the right to belong.

#iBelong https://t.co/Kw1p3n4UMA pic.twitter.com/Pz5K4EzdLC— UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency (@Refugees) February 14, 2019

The consequences of statelessness extend far beyond the individuals affected. The continued economic and social development of entire states could be at stake.

With large sectors of the population unable to participate in the workforce due to legal constraints associated with graduation certificates and eligibility requirements, the potential for productivity and economic growth may also be hindered.

Further, social tensions and alienation within communities provide a ripe climate for elevated levels of conflict.

#IBelong and Beyond

The 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda seeks to eliminate childhood statelessness through “achieving legal identity for all through birth registration.”

In 2014, UNHCR launched the #IBelongCampaign to raise public awareness of childhood statelessness and pressure states into concrete action to meet this goal.

Through creative engagement, #IBelong has cast a broad focus on several key regions in Europe and across the world aiming to boost social consciousness of the issue.

In 2016, Senegalese rock group Bideew Bou Bess released the song, “I Belong,” and throughout 2018, busses in downtown Luxembourg displayed advertisements urging people to join the campaign.

To mark the midpoint of the campaign, a formal High-Level Event on Statelessness will convene in Geneva in October 2019. The European network on Statelessness and the UNHCR/UNICEF brief have emphasized their desire to end statelessness by 2024.

“We’re looking for pledges related to steps governments will take in the remaining 5 years of the campaign to help end statelessness, including accession to the two U.N. statelessness conventions, adoption of safeguards in nationality laws that ensure that all children acquire a nationality at birth, and the removal of all forms of discrimination from nationality laws,” UNHCR Spokeswoman Elizabeth Throssell told The Globe Post.

Since the #IBelong Campaign launched in 2014, nine states have improved or established statelessness determination procedures, and six states have created streamlined processes for naturalization.

National plans to end statelessness and meet the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals have been formally adopted in nine states.

In Thailand alone, it is estimated that over 27,000 formerly stateless persons acquired Thai nationality since 2012, and up to 80,000 more could acquire nationality by 2024.

But with migration levels expected to remain high in Europe in the coming years, staying on track to eradicate childhood statelessness by 2024 will require greater political will by state governments if the goal is to be met.

More on the Subject

Rights activists accused Europe in January of clinching a new “record of shame” with its refusal to open ports to migrant children and families stranded at sea in the Mediterranean.

The latest standoff involves 32 migrants who were rescued at sea on December 22 but have not yet been given permission to land anywhere.

‘Record of Shame:’ European Ports Remain Closed to Sick Children