Last month marked the loss of a World War II icon. George Mendonsa, the sailor famously photographed while kissing an unsuspecting woman in New York Times Square, passed away at the age of 95. In memoriam, an unidentified vandal marked a statue commemorating this kiss with the phrase “#MeToo.”

The ecstatic sailor shown in an iconic photo kissing a woman in Times Square celebrating the end of World War II has died. George Mendonsa was 95. https://t.co/wzSfgLxW2X pic.twitter.com/skRgcYGp7O

— ABC News (@ABC) February 18, 2019

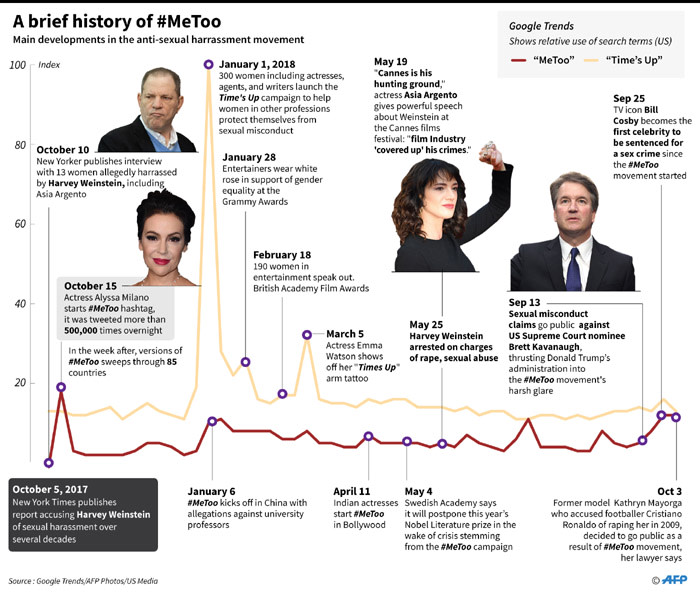

The rebranding of this once romanticized encounter between two strangers in the streets of New York underscores the fact that we now live in the #MeToo era. Sexual harassment and assault have entered international discourse and survivors are speaking up.

Findings from a recent survey completed by more than 30,000 United Nations staff and personnel revealed that one in three respondents had experienced at least one incident of sexual harassment or assault in the workplace within the last two years. The highest prevalence rates were reported by females and respondents who identified as LGBTQ, transgender, or gender nonconforming. Two out of three perpetrators were male.

#MeToo has undoubtedly put sexual harassment and assault on the digital map, but what is the trajectory of this hashtag movement? Where has it been and where has it taken us?

Beginnings of #MeToo Era

The #MeToo movement was launched over a decade ago in Brooklyn, New York as a grassroots effort to build a community of advocates for young women of color and/or economic disadvantage who were survivors of sexual assault.

Founder Tarana Burke was compelled to take action after grappling with the memory of a young girl who, at a youth camp, disclosed she was being sexually abused. Horrified by the girl’s story, Burke turned the girl away and was haunted by her inability to listen, help, or even utter the words “me too.”

In October 2017, the #MeToo movement traveled from the streets of Brooklyn across the world wide web when actress Alyssa Milano encouraged survivors of sexual harassment and assault to show solidarity by tweeting two words: “Me Too.”

One year and millions of tweets later, the New York Times credited the #MeToo movement with the downfall of a hoard of powerful American men accused of sexual misconduct, ranging from entertainment industry moguls and politicians to CEOs.

Consequences of #MeToo

It is not surprising that a movement popularized by a celebrity would hold famous men accountable for alleged misconduct. However, focusing on the consequences of #MeToo among the famous only tells part of a much larger story.

A recent Pew Research Center report indicates personal narratives are just as prevalent in #MeToo tweets as celebrity stories. This, paired with the grassroots origins of the movement, should remind us to look beneath the shadows of fallen entertainers and politicians to examine the consequences of #MeToo for the average survivor.

Considering the fact that #MeToo generated more than 19 million tweets in its first year, it is safe to conclude that this hashtag has provided a public forum for survivors to be counted and heard. However, experts disagree on the consequences of such hashtag activism on survivors.

Critics have argued that #MeToo builds a circumscribed space for voicing moral outrage where expressions of negative emotions in the online world replace more meaningful activism in the offline world. Others have suggested women’s participation in such digital activism may be safer than offline activism; internet trolling seems less threatening than face-to-face opposition.

Backlash

Opposition and backlash are seemingly inescapable reactions to social activism – and this certainly applies to #MeToo. Perhaps the most prominent backlash has come from U.S. President Donald J. Trump who famously claimed:

“it’s a very scary time for young men in America … My whole life, I’ve heard you’re innocent until proven guilty … but now you’re guilty until proven innocent.”

This sentiment is resounding. Poll data collected in November 2017 and again in September 2018 show an increase in the proportion of American respondents who agree with the statements “False accusations of sexual assault are a bigger problem than unreported assaults” and “Women who complain about sexual harassment cause more problems than they solve.”

Men oppose #MeToo more often than women, but the movement does have male allies. Shortly after Alyssa Milano inspired survivors to speak out with the #MeToo hashtag, an Australian journalist asked men to reflect on their role in either preventing – or perpetrating – violence against women with the #HowIWillChange campaign.

Guys, it's our turn.

After yesterday's endless #MeToo stories of women being abused, assaulted and harassed, today we say #HowIWillChange.

— Benjamin Law 羅旭能 (@mrbenjaminlaw) October 16, 2017

This effort compliments larger offline activism which, for the past few decades, has focused on enlisting men as allies in preventing violence against women. However, it is unclear how helpful this has been, as a textual analysis of #HowIWillChange tweets revealed a mix of sincere interest in violence prevention and resistance to social change – with some resistance expressed as hostile opposition.

Such backlash suggests a need to enlist the support of online bystanders to intervene on behalf of survivors and allies who are targeted by hostile opponents of the #MeToo movement.

Bystanders

Since the 1990s, advocates have approached bystanders in the offline world as a vital force in preventing sexual violence by encouraging them to intervene when witnessing violence, warning signs of violence, or jokes that condone sexism and violence. There is empirical evidence indicating individuals who are trained to intervene will actually take action when circumstances warrant that they do so.

Perhaps such programs should extend the scope of bystander intervention to include supporting survivors in the online world. The presence of an online community of bystanders posting support for sexual assault survivors whose #MeToo stories are attacked may reduce any trauma inflicted by online trolls – and may even buffer the influence of hostile opponents on the opinions of the larger online audience.

Still, as #MeToo has moved from grassroots advocacy to international activism, its tangible consequences in the offline world are not entirely clear. The relative newness of #MeToo hashtag activism has allotted little time for the accumulation of empirical evidence of its effects on rates of sexual misconduct, emotional wellbeing of survivors, or patterns of holding perpetrators accountable. We also know little about the effects of male allies’ hashtag activism on men’s behavior in the offline world.

Only when a sizable body of research accumulates will we know the tangible consequences of living in this #MeToo era.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of The Globe Post.