With almost four years since the onset of the largest arrival of migrants to E.U. territory since World War II, tensions on how to tackle the new arrivals from North Africa and the Middle East remain high, as member states stand divided on the question of sharing responsibility.

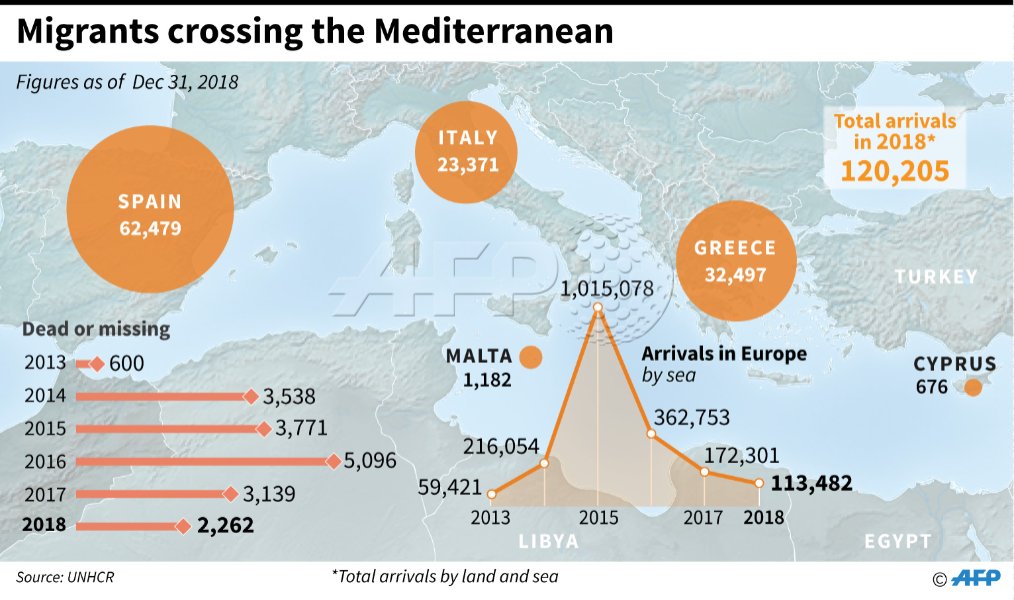

In 2015, over a million people arrived in the E.U. through Italy and Greece. This mass arrival prompted an E.U.-wide crisis. The existing mechanism for dealing with asylum arrivals – the Dublin Regulation – became patently insufficient in channeling the asylum inflows.

Although the E.U.’s strategy of outsourcing responsibility to Turkey, under the 2016 E.U.-Turkey statement, has been credited for curbing asylum arrivals to Greece, it has not resolved the ongoing crisis at the E.U.’s southern borders.

Deaths Across Mediterranean

A UNHCR report from the end of last year shows that while the total number of arrivals to the E.U. has dropped, the rate of deaths across the Mediterranean has sharply increased. Rising from a ratio of 1 death per 269 arrivals in 2015 to 1 death for every 51 in 2018, the Mediterranean route remains the world’s most dangerous maritime crossing for migrants.

The growing number of deaths in the Mediterranean Sea has been attributed to several factors, including the E.U.’s agreement with the Libyan border and coast guard. The humanitarian crisis in the Mediterranean is also, importantly, a product of intra-E.U. conflict over asylum responsibility.

Refusing Rescue Vessels

In December, Italy’s Deputy Prime Minister Matteo Salvini tweeted that “Italian ports are CLOSED.” His tweet followed on from a series of decisions taken by the right-wing government to close the country’s ports to NGO and humanitarian ships carrying migrants.

AGGIORNAMENTO

“#SeaWatch3”, altra nave di un’altra Ong (bandiera olandese), chiede di portare in Italia decine di immigrati recuperati al largo delle coste libiche.

La mia risposta non cambia: i porti italiani sono CHIUSI, stop al traffico di esseri umani!#portichiusi— Matteo Salvini (@matteosalvinimi) December 23, 2018

In June 2018, over 600 migrants on board of the rescue vessel Aquarius were refused disembarkation by the Italian and Maltese authorities. Six months later, the Italian government also denied entry to Proactive Open Arms and the German rescue vessel Sea Watch 3.

The German migrant rescue group Sea Watch has recently lodged a complaint against Italy at the European Court of Human Rights for refusing to allow the rescue vessel to dock at its port. The group decried the actions of the Italian government arguing that it can “no longer accept that the European states are jointly breaking the law of the sea.”

The Italian government has, however, defended its migration strategy arguing that although “saving lives is a duty… turning Italy into a huge refugee camp is not.”

The refusal by Italy to allow NGO and humanitarian rescue ships to disembark on its territory is a part of the new populist government’s migration strategy. While Salvini’s actions reflect the restrictive and xenophobic preferences of his far-right political party, the frustration over the disproportionate pressure on Italy to tackle migration inflows has been a long-standing national contention.

EU Asylum Laws

Even though the restrictive direction of the Italian government’s migration policy warrants criticism, the crux of the political unrest over disembarkation lies within the E.U.’s asylum laws.

The E.U. does not have a system for the “fair sharing” of the administrative, legal, and financial costs associated with the processing of asylum applications and integration. In fact, the design of the E.U.’s asylum responsibility allocation system has produced an unequal distribution of responsibilities.

By designating asylum responsibility on the basis of irregular entry, the system has placed additional pressure on frontline states who, because of their geographical position, constitute the main entry points into E.U. territory.

In his first speech as Italian Prime Minister, Guiseppe Conte called for the overhaul of the Dublin Regulation to “ensure that the principle of fair distribution of responsibilities is respected” and establish an “automatic and obligatory” system of resettlement for asylum seekers.

Yet, the continued lack of agreement among member states on an alternative allocation system has impeded a more ambitious reform. Proposed by the European Commission in 2016, the European Council negotiations on a new Dublin system remain in deadlock.

Political Impasse on the Dublin Regulation

The three-year political impasse on the Dublin Regulation recast alludes to the depth of division among E.U. member states on the question of responsibility distribution and mandatory relocation. Southern member states are demanding a fairer system to which all member state must contribute. However, some other countries refuse to accept different and fairer rules that may require them to take on more of the asylum “burden.”

Some steps were taken last year under the Bulgarian and Austrian presidency to move toward a compromise, but Southern Mediterranean states have refused any agreement that does not include compulsory relocation.

With member states increasingly focused on the external aspects of migration and cooperation with third countries, reforming the Dublin system is no longer a top priority. This indicates a worrisome lack of political will from the member states to tackle the divisive issue.

In Search for EU Leadership

Even more alarming has been the retreat of the Commission’s leadership on the overhaul of the E.U.’s asylum system.

At the height of the refugee crisis, Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker announced that the Commission was adopting a new approach to asylum that would involve a “more fundamental change in the way we deal with asylum applications… notably the Dublin system.” Initially positioning itself as a “very political” actor ready to challenge the “business as usual” approach to asylum, the Commission has now traded ambition for pragmatism.

The recast proposal not only maintains the problematic rules on responsibility allocation, but it also introduces a new permanency to responsibility.

The European Commission’s prioritization of the external aspects of migration also indicates a reluctance to push for a consensus on the Dublin system and a mandatory relocation scheme in fear of antagonizing unwilling member states. This in part stems from the backlash it experienced regarding the emergency relocation schemes that were adopted in 2015 without the full support of the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia.

The European Parliament has conversely adopted an ambitious negotiating position that includes a permanent and immediate relocation system. The European Parliament has criticized the Council’s three-year delay in adopting a negotiating mandate, with prominent party leaders such as Guy Verhofstadt threatening to bring the Council to court under Article 265 of the Lisbon Treaty for the “failure to act.”

Current State of Play

The promise of negotiating conflict between the European Parliament and the Council is, however, far off. Without a consensus in the Council, the progress of reform is stalled at an early stage.

The inability to reach a consensus among the member states has been exacerbated by the domestic politics of some of the states where right-wing parties politicize the issue of migration for political gain.

While the E.U. struggles to find a solution to its Dublin problem, migrants continue to risk their lives in perilous journeys across the Mediterranean Sea. In the absence of a fairer system of distribution for migrant arrivals, these journeys are made even more treacherous by the steadfast willingness of member states to gamble on migrant lives in a race to avoid responsibility.