Humanitarian conditions in Haiti have significantly worsened over the past year, the U.N.’s Assistant Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs Ursula Mueller warned in an address earlier this month.

Hunger levels are on the rise and more than half of Haiti’s population lives below the poverty line. Access to basic services is very limited and more than a quarter of Haitians lack clean water to drink. Some 2.6 million people are expected to be in need of humanitarian assistance in 2019, and more than 300,000 children are unable to get an education.

Yet the world has largely turned its back on the poorest country in the Western hemisphere.

In 2018, the U.N.’s appeal for Haiti was funded at just 13 percent, making the country the site of the world’s most underfunded humanitarian crisis.

“Sadly, the severe levels of humanitarian need in the country rarely make headlines,” Mueller lamented.

A Tale of Two Countries

On top of the dire humanitarian situation, a political crisis is unfolding in Haiti as well.

Angered at the country’s ever-diminishing economic prospects, thousands have taken to the streets in recent months calling for President Jovenel Moïse to leave office.

But unlike the ongoing political crisis to the South in Venezuela, the protests in Haiti have also received little attention from Western leaders and the major international press.

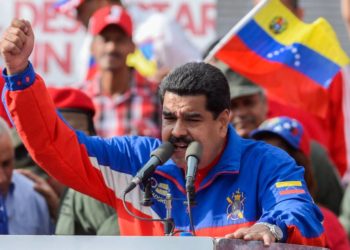

As the first country to recognize Venezuelan opposition leader Juan Guiado’s claim to the presidency, the United States has played a leading role in efforts to oust President Nicolas Maduro from power.

U.S. officials claim the 2018 elections that saw Maduro win another term were “illegitimate,” and that Maduro’s incompetence and corruption are the root of Venezuela’s sharp economic decline.

With President Donald Trump’s administration committed to regime change in Venezuela, major American cable news programs and print publications have paid close attention to the humanitarian situation there.

Lost Faith

But questions surrounding the legitimacy of Haiti’s Moïse, as well as allegations of corruption and mismanagement, have also been persistent.

In addition to allegations of fraud, widespread disillusionment and systemic barriers to voting resulted in only about 20 percent of Haitians casting ballots in the 2016 elections that brought Moïse to power, Jake Johnston, an analyst at the Center for Economic and Policy Research, told The Globe Post.

“For me, the biggest indicator of election’s declining legitimacy is evidenced by the increasingly declining turnout,” he said.

“Is it really a surprise when a lot of people don’t actually respect the government’s legitimacy or mandate when so few people actually participate?”

Marlene Daut, a professor of African Diaspora Studies at the University of Virginia, agrees.

“On the U.S. side, we tend to think that as long as there are elections, we can say someone was ‘democratically elected,’” she told The Globe Post.

“But the feeling in Haiti is …they have lost faith in the electoral process.”

Funds, Squandered

Like in Venezuela, perceptions of widespread corruption have also plagued the Haitian government.

From 2005 until recently, Haiti received some $4 billion in petrol loans as part of a program called Petrocaribe that was initiated by former Venezuelan president Hugo Chavez.

The loans were intended to allow Haiti and other Carribean countries to invest in programs like schooling, healthcare and infrastructure, but Haiti’s public sector ultimately saw little of the money.

Additionally, Moïse has been at the center of a recent high-profile corruption scandal involving American “mercenaries” who were reportedly hired by him to transfer $80 million from the country’s national bank to a personal account of his.

Geopolitics

So what explains the vast disparity in responses to the political and humanitarian crises in Venezuela and Haiti?

According to Daut and Johnston, the answer boils down to geopolitics.

“I don’t think that the U.S. government is interested in democracy or human rights or that those are the motivating factors behind what they’re involved in Venezuela,” Johnston said.

Venezuela’s government has pursued a socilaist strand of independent development following the election of Chavez in 1999, and has since aligned itself with countries like Russia and China.

Haiti’s government, on the other hand, has largely played by the rules set out by the U.S. In some sense, efforts from American administrations throughout history have ensured this.

U.S. involvement in Haitian politics dates back to at least to the early 20th Century when the island was occupied by American Marines between 1914 and 1934. Throughout much of the rest of the century, the U.S. supported the brutal regimes of Francois Duvalier and his son, Jean-Claude.

In 1990, when Haiti surprised Washington by electing the populist liberation theologist Jean Bertrand Aristide, the George H.W. Bush administration supported a military coup that quickly deposed him.

Since then, a line of Haitian governments have generally aligned themselves with the U.S., embracing Washington’s preferred brand of “neoliberal” policies and opening the country to foreign investment.

“Haiti, since colonial times has been built around an extraction of wealth and distribution to other parts of the world,” Johnston said. “This has been the economic model in Haiti for centuries that in many ways continues today.”

Continuing Cycle

While those on the ground in Haiti are largely more concerned with the daily economic struggles they face, Daut said there is a “strong feeling” among Haitian Americans that recent presidents have been “installed” by the U.S.

As protests continue throughout Haiti, Moïse’s relationship with Washington appears to be stronger than ever.

After Haiti voted with the U.S. in the Organization of American States to recognize Guaido as interim president in Venezuela, Trump sat down with Moïse at Mara Lago last week, and the U.S. is reportedly helping to broker a debt relief agreement between Haiti and Qatar.

And though there appears to be no immediate threat to Moïse’s power, Johnston said he expects popular pressure on the government won’t stop any time soon.

“The underlying issue is a political and economic system that excludes far too much of the population,” he said.

“Until those root problems are addressed, I see that cycle continuing into the future.”

More on the Subject

Opinion: Haiti’s Recent Protests Expose the Lie of Democracy