When children, women, and men escape the torture camps in Libya via the Mediterranean Sea, something odd seems to happen, more frequently now than before. The names ascribed to them change, as if the passage through the sea and their growing proximity to Europe altered their identity.

Once described as individuals or just people, as migrants or refugees, as victims or survivors of torture, sexual violence, and even slavery, they become something else: criminals, hijackers, and pirates. Such a transformation of identity could be observed merely a few days ago when a migrant boat sought to reach Europe from Libya.

Rescued at sea by the tanker El-Hiblu 1 after its crew was asked to do so by a European aircraft, the 108 migrant travelers were initially not informed about the intention to return them to Libya. If returned, this would have breached international law, maritime law, and refugee conventions, as the northern African country cannot be considered a port of safety or a place where the disembarked would be protected from persecution.

Once the group consisting of children, men, and women realized that they were nearing Libya’s capital Tripoli, some of them began to protest, reportedly forcing the crew of the tanker to change course and steer north towards Europe.

Portrayal of Migrants

For Italy’s extreme-right Minister of the Interior Matteo Salvini, the verdict was clear. The rescued were not migrants but pirates who had hijacked the tanker.

The Maltese army boarded the vessel and escorted it into the harbor of Valetta where the 108 disembarked, with three African teenagers now facing charges of “terroristic activities.” Despite the remaining 105 migrants seemingly being freed of allegations of wrongdoing, Salvini’s initial portrayal of these migrants as criminals and pirates stuck and was circulated in international media.

However, for the ones reportedly threatened, the crew of the El-Hiblu 1, the migrants, including the three scapegoated teenagers, were refugees, not terrorists. The owner of the tanker emphasized their right to fight for their lives and survival.

Bleak Prospects in Libya

Though much remains unclear about the case of the El-Hiblu 1, it gives evidence once more to the devastating situation that migrants face in Libya, and the desperate need to escape. For the many thousands who are returned to Libya by the so-called Libyan coastguards or commercial cargo vessels, the prospects are bleak.

Many testimonies collected by human rights organizations make it dauntingly clear that little has changed over the past years. The camps, characterized in 2017 by German diplomats as “concentration-camp-like,” continue to function as both containment and extortion zones of captured migrants.

A recent report by the Women’s Refugee Commission has shown what has been widely known and documented before: the abyssal and systematic forms of violence that migrants are exposed to when seeking to reach and then leave the northern shore of Africa. The details of their suffering in Libya stretches the imagination of cruelty, with rape, torture, exploitation, and extortion being everyday experiences.

Refoulment Industry

E.U. institutions and member states are fully aware of this Libyan hell, and yet, nothing is being done to improve the situation. Quite the opposite is the case: despite its fluidity, the Mediterranean Sea is continuously turned into a “hard” border, with European states and E.U. agencies colluding with north African authoritarian regimes and even Libyan militias and smugglers to stem outward migration flows.

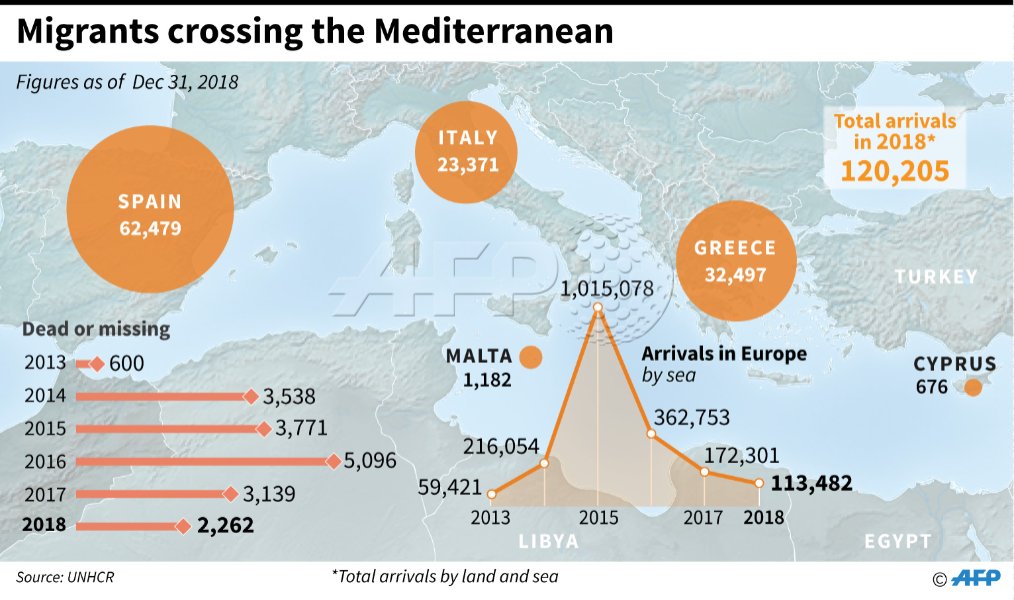

What I have termed a “refoulment industry,” the concerted effort to return escaping migrants by boat to northern Africa, normalizes breaches of international and maritime laws and refugee conventions. The decline via this central migration route has been dramatic: while over 119,000 escaped Libya in 2017, the figure dropped to about 23,000 in 2018. And so far in 2019, merely 500 people have successfully fled.

For those who fall victim to this refoulment industry, the hope to ever escape the Libyan hell is dwindling. And yet, many will not cease to locate escape routes; they simply have to. They have invested heavily to fund their migration projects, often with the support of families and communities. Their odyssey was costly and did not begin in Libya but long before, when they had to cross several borders, including the dangerous Saharan desert.

With time passing in Libyan detention, many are repeatedly exposed to extortion practices, which adds to the growing mountain of debt. Besides the financial aspect, all have paid dearly for their wish to find a better future, with their physical and mental well-being seriously harmed. They simply need to get out of Libya and reach a place of safety. But when these survivors board boats, they turn from those who have experienced unimaginable cruelty into migrant pirates.

Consequences of EU Policies

Europe is to blame for repeatedly denying these survivors their futures in peace and freedom. The E.U.’s obsessive focus on border “protection” and the reduction of migrant arrivals has allowed an excess of violence that travels much further south than the Mediterranean.

This system of abuse will leave yet another a dark mark on Europe’s history, and is only confronted by the migrant travelers themselves, who tend to move on despite all obstacles, and the few humanitarian rescuers and activists who continue to struggle on to turn the Mediterranean into a less deadly space.

Besides supporting those who move and those who aid them, we need to find other names for those who risk the Mediterranean passage. We need to resist the spectacle of sensational names such as pirates, hijackers, and terrorists, which the international media is too eager to circulate without much introspection.

It is time to view migrants who move precariously as individuals, as sons and daughters, mothers and fathers, and friends and partners who collided with a cruel and heartless European border regime when enacting their longing for freedom in movement.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of The Globe Post.