It has been eight years since the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami destroyed the emergency generators that cooled the reactors at Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. The reactors shut down during the earthquake but remained vulnerable to the tsunami. This caused a catastrophic meltdown of the reactor cores, peppering the local Japanese landscape with radioactivity.

In 2016, three former electric utility company TEPCO executives were finally charged with negligence for not taking appropriate preparedness measures in advance of the disaster. However, the challenges that this region faces are ongoing.

We now know that Fukushima was the most serious nuclear accident since Chernobyl. Many challenges and uncertainties have arisen since the accident, affecting the local environment, nuclear industry, and communities that lived and worked nearby.

Fukushima has also had an international impact on our perception and understanding of nuclear energy, at a time of pressing need for fossil fuel alternatives due to climate change. As TEPCO begins to decommission Fukushima, what have we learned from this disaster?

Consequences of Fukushima

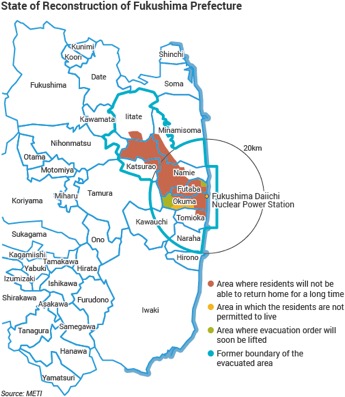

The Fukushima Daiichi catastrophe has changed the landscape of the region. From 2012, Special Decontamination Areas were introduced across a 20-kilometer radius surrounding the accident. These zones have dramatically depopulated the area, and Fukushima has become a place synonymous with risk.

Approximately 160,000 people were evacuated from their homes following Fukushima, and there have been social and health consequences to this forced relocation. A report by the Reconstruction Agency in 2012 surveyed 1,500 Fukushima workers and discovered that 70 percent was stressed due to evacuation and 50 percent believed that they had come close to death.

While no deaths have arisen due to ionizing radiation exposure itself, the Fukushima Reconstruction Agency has identified 1,656 fatalities that have occurred due to the effects of evacuation. Of these deaths, 90 percent occurred among people older than 66 years. These fatalities arose due to the physical and mental stress of living in evacuation shelters, delays in obtaining medical support during evacuation, and suicide. This demonstrates the harmful physical and mental health effects of long-term evacuation programs.

Displaced People of Fukushima

The areas that are closest to Fukushima Daiichi remain no-go zones, and the people that lived in these regions may never go home. About 81,000 people remain displaced. The International Atomic Energy Agency has clarified that many evacuees across the 20-kilometer radius could return home, but a Mainichi report showed that 78.2 percent of Fukushima evacuees preferred to remain where they are and that only 18.3 percent intended to move back to the prefecture.

For example, the evacuation order has been partially lifted in Okuma, but currently, only 367 people, about 3.5 percent of its pre-disaster population, have registered to return. Evacuees are now concerned about potential future radiation exposure, as Okuma includes an interim storage site for radioactive contaminated soil, that will remain in place until 2045. This is despite government financial support for voluntary evacuees ending in March 2017. There are plans to end all housing subsidies for evacuees by March 2021, a target that may have further harmful consequences to the displaced people of Fukushima.

While the United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation and World Health Organization report that there will be no increase in miscarriages, stillbirths or physical and mental disorders in babies born after the accident, concerns have remained among the affected community.

In the eight years after the disaster, the families of Fukushima have made lives for themselves elsewhere. Despite a new town hall and other infrastructure projects across the region, there are few incentives for evacuees to return.

Nuclear Work

Extensive decontamination work is ongoing at the Fukushima Daiichi site and is anticipated to continue for the next 40 years, at a cost of $189 billion. There are 1,573 highly reactive spent and unspent fuel rods stored at the facility that must be removed, and progress has been slow due to earthquake debris inside the building and other technical issues.

A recent two-year program has begun to remove the first of 566 fuel assemblies from reactor 3. This is a delicate operation, requiring remote underwater work to shield these highly radioactive materials. The most difficult phase will be to remove molten nuclear fuel from the facility, which begins in 2021.

This work is undertaken by 4,000 workers daily. However, nuclear workers in Japan who receive an occupational dose of 50 millisieverts in a year, or 100 millisieverts over five years, become ineligible to work with ionizing radiation, causing a shrinking pool of suitable workers.

Japan needs thousands of foreign workers to decommission #Fukushima plant, prompting backlash from anti-nuke campaigners and rights activists https://t.co/zC1gzAz7Ae pic.twitter.com/XfgSpXOG0f

— Reinhard Uhrig (@reinharduhrig) May 2, 2019

The Japanese Government recently introduced a new working visa scheme on April 1, and TEPCO has informed subcontractors that overseas nationals will be eligible to work on the Fukushima clean-up. While TEPCO has stated that migrant workers must have Japanese language skills and will be required to carry radiation exposure monitors, this scheme has been condemned by both anti-nuclear campaigners and human rights activists.

Hajime Matsukubo, secretary general of the Tokyo-based Citizens’ Nuclear Information Centre, said that “Conditions for foreign workers at many companies across Japan are already bad but it will almost certainly be worse if they are required to work decontaminating a nuclear accident site.”

There are concerns that migrant workers will not understand the risks that they might face. There are also challenges in determining migrant nuclear workers’ prior radiation exposures, in tracking their long-term wellbeing, and in providing compensation should they experience later health consequences in their country of origin.

With the 2020 Tokyo Olympics impending and Fukushima’s Tsurugajo Park set to have a site, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is trying to rehabilitate the region’s reputation and show-case its recovery. However, Japan’s Olympic Minister Yoshitaka Sakurada resigned in early April this year, after making comments that were offensive to the people affected by the disaster.

For evacuees who have to return in 2021 and the migrant workers of Fukushima Daiichi, there could be long-term cultural, social, and mental health costs.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of The Globe Post.