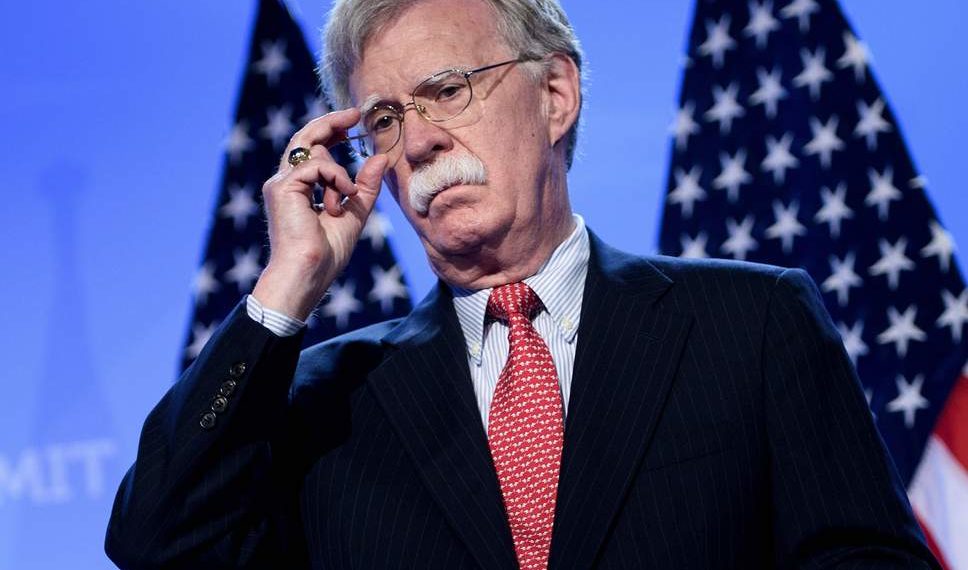

On April 17, John Bolton walked onto a stage at the Biltmore Hotel outside of Miami, Florida to a warm reception from the small, mostly Cuban American crowd on hand for his remarks. Behind the podium hung the yellow and blue flag of Brigade 2506, the CIA-sponsored group of Cuban exiles who led the failed Bay of Pigs invasion to overthrow the government of Fidel Castro exactly 58 years earlier.

The national security advisor used the occasion to announce new sanctions against Cuba, Venezuela, and Nicaragua as part of a broader campaign from the Donald Trump administration against socialism in Latin America.

“We proudly proclaim for all to hear: The Monroe Doctrine is alive and well,” Bolton said, referencing the imperial 19th Century policy asserting U.S. dominion over the Western Hemisphere.

Bolton and other Trump administration officials have framed the campaign as a benevolent crusade against authoritarianism in the name of freedom and democracy. Cuba’s Miguel Díaz-Canel, Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro, and Nicaragua’s Daniel Ortega represent a “troika of tyranny,” Bolton said, adding that “the U.S. looks forward to watching each corner of this sordid triangle of terror fall.”

But others who have closely studied U.S. policy towards the region throughout history say the campaign has nothing to do with freedom, democracy, or human rights. From their perspective, the Trump administration’s Latin America policy is about power and domination – the latest stage of a long-running effort to exercise control over the hemisphere and its resources.

Among those advocating this point of view is Noam Chomsky, the great linguist and renowned American dissident. In 1979, Chomsky was dubbed “arguably the most important intellectual alive” in the New York Times. Fourty years later, at the age of 90, he remains one of the most influential and widely-read critics of U.S. foreign policy.

To Chomsky, there’s no contradiction in opposing U.S. policy and acknowledging the abuses of some of the regimes being targeted by Washington.

“There are plenty of grounds for criticism of the governments (countries) under attack,” he told The Globe Post in an email.

Díaz-Canel, Maduro, and Ortega have all been widely criticized to varying degrees for their corruption, authoritarian tendencies, and for suppressing the rights of their citizens. Still, “those are at most pretexts, not reasons for the assault,” Chomsky said.

And while Bolton and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo are “an unusually brutal pair of thugs, who are happy to use force and economic strangulation to ensure that the world fears U.S. power,” he said, “their policies don’t break new ground in any fundamental way.”

‘Our Hemisphere’

Six months after the end of the second world war, the United States organized a hemispheric conference in Mexico City with the goal of creating an “Economic Charter of the Americas.” Having emerged from the war as a superpower, the U.S. was now in position to spread its influence across the globe in a way that had never been possible before.

The Latin American representatives arrived at the conference promoting “the philosophy of the New Nationalism,” described by a U.S. official as one that “embraces policies designed to bring about a broader distribution of wealth and to raise the standard of living of the masses.” As State Department advisor Laurence Duggan put it, “Latin Americans are convinced that the first beneficiaries of the development of a country’s resources should be the people of that country.”

This was unacceptable to the U.S. representatives, who felt that the interests of U.S. investors should be prioritized above all else. Thus, a general model for Latin American development was created that has remained largely persistent until today. As Chomsky describes it, “the first beneficiaries are U.S. corporations and investors, accommodated by local elites who enrich themselves while the general population struggles to survive.” Governments that embrace the model are rewarded by Washington, often with military and economic aid. Those that do not are crushed. After all, as Bolton recently told the New Yorker, “it’s our hemisphere.”

From this perspective, U.S. policy towards the region is not fundamentally about socialism per se. Daniel Bessner, a historian of U.S. foreign policy and a professor at the University of Washington’s school of international studies, argues that Washington’s main objection to governments like those in Cuba, Venezuela, and Nicaragua is not about their leftist ideology, but their willingness to defy the U.S.

“The first beneficiaries are U.S. corporations and investors, accommodated by local elites who enrich themselves while the general population struggles to survive.”

Like Chomsky, Bessner flatly rejects U.S. officials’ claims that their policies are based on humanitarian concerns, pointing to the fact that Washington has long supported authoritarian leaders around the world “if they view them as being in their own best interest.”

“People do have genuine humanitarian interests, but they’ve been used for so long as a cover for American imperialism,” he said.

Instead, Bessner points to a confluence of factors that motivate U.S. foreign policy decisions behind closed doors.

“The major reason that the [U.S.] intervenes is not necessarily to put down the left, even though that became something that it dedicated itself to later on,” he told The Globe Post. “Really, it’s to control all of the resources in the region.”

Defiance

Disentangling these motivations can be difficult, Bessner said, particularly after the break out of the Cold War, when the lines between socialism and capitalism overlapped with the broader geopolitical competition between the U.S. and the Soviet Union.

“The people who are the makers of American foreign policy were raised during this Cold War period and are very embedded in this anti-left-wing ideology,” he said. “But at the same time, there is still a genuine interest to control the entire region in order to gain access to its raw materials and ensure that no other non-Western Hemispheric power is able to exert any influence on what is considered to be, in the United States’ mind, it’s own backyard.”

U.S. policy towards Cuba, for example, has embodied these overlapping concerns. While officials in Washington were certainly worried about the potential for a Soviet foothold there that could threaten American security, they also feared that Castro’s model of independent nationalism could spread throughout the region and damage U.S. economic and political interests.

“There is still a genuine interest to control the entire region.”

During the tenure of President John F. Kennedy, a State Department memo explained that “the primary danger we face in Castro … is in the impact the very existence of his regime has upon the leftist movement in many Latin American countries … the simple fact is that Castro represents a successful defiance of the U.S., a negation of our whole hemispheric policy of almost a century and a half.”

In response, the Kennedy administration sought to unleash “the terrors of the Earth” on Cuba in hopes of quarantining Castro’s model. The CIA organized a covert, violent sabotage campaign that terrorized the island while U.S. officials imposed an economic blockade that’s continued, in some form, until today. Similarly, when Chilean socialist Salvador Allende – a moderate compared to Castro – was elected in 1970, President Richard Nixon’s administration decided to “make the economy scream.” The policy culminated in a U.S.-backed coup three years later which saw Allende deposed and the brutal, far-right dictator Augusto Pinochet rise to power.

Under similar circumstances, the U.S. has worked to topple a long list of Latin American governments in Honduras, Haiti, Argentina, Nicaragua, Ecuador, Brazil, El Salvador, Venezuela, and Columbia, among others. These efforts have ranged from overt support for military overthrows to what Chomsky called “a soft coup” in Brazil in recent years, which allowed far-right, U.S.-friendly President Jair Bolsonaro to come to power while his primary political opponent, former leftist President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva sat in prison with the help of the U.S. Justice Department.

‘They Want The World’

In the case of Venezuela, the U.S. has attempted to deploy the former strategy since 1999, when its people elected leftist leader Hugo Chavez. His Chavismo movement sought to bring the nation’s resources, most importantly its vast oil reserves, under public control to the exclusion of outside investors and corporations. In 2002, the U.S. openly supported a military coup that ousted Chavez, but only briefly.

Now, the Trump administration is supporting U.S.-friendly opposition leader Juan Guaido’s effort to overthrow Chavez’s successor, Maduro. In January, Guaido declared himself president in close coordination with Washington, which swiftly recognized him as the country’s “legitimate” leader along with about 50 other U.S.-aligned countries. But Maduro remains in power on the ground, and several attempts to topple his government have failed.

These efforts have not come without severe humanitarian consequences for the Venezuelan people. The country’s economy is facing a severe crisis, which U.S. officials have blamed squarely on Maduro’s mismanagement and incompetence. On Saturday, the front page of the New York Times featured a disturbing image of malnourished Venezuelan children above a sub-headline reading, “mismanagement brings a country to its knees.”

But a recent study from economists Mark Weisbrot from the Center for Economic and Policy Research and Jeffery Sachs from Columbia University estimated that sanctions, imposed in two main stages by the Trump administration since 2017, have resulted in the deaths of about 40,000 Venezualans. Weisbrot told The Globe Post that Maduro’s mismanagement has been a significant factor in the country’s economic downturn, but that the role of sanctions in preventing a recovery has been widely overlooked in the narrative around the crisis.

“There’s just no way around it,” he said. “Everybody knows it, but there’s a state of denial.”

The study found that U.S. sanctions “have inflicted, and increasingly inflict, very serious harm to human life and health,” as they have prevented the government from importing adequate amounts of medicine, food, medical equipment, and parts to maintain the country’s public infrastructure. The measures are also projected to result in a “cataclysmic and unprecedented” 67 percent drop in oil export revenues in 2019, while the International Monetary Fund projects a 25 percent fall in GDP for the year.

“These numbers by themselves virtually guarantee that the current sanctions, which are much more severe than those implemented before this year, are a death sentence for tens of thousands of Venezuelans,” the researchers conclude, arguing that the measures are a form of “collective punishment” that violate a host of international laws.

“They want the world. They want the whole hemisphere to be theirs.”

Officials in Washington argue that the sanctions are targeted solely against the Maduro regime. But Nicholas Mulder, a historian of economic sanctions at Columbia University, told The Globe Post that even sanctions that are intended only to affect certain individuals and entities often have much broader humanitarian impacts.

“Most pundits and even a lot of sanctions specialists do not always appreciate that once you impose these kinds of economic measures, you no longer control all of their second- and third-order effects – as with any economic policy introduced into the real world,” he said.

Mulder also said it’s important to draw a distinction between the effects of sanctions and their efficacy. In the case of Venezuela, the sanctions have had a broad range of effects, but they’re yet to bring about their stated objective, the removal of Maduro.

“There is no question that the United States has an enormous ability to drive the economy of other countries, especially small and medium-sized economies, into the ground,” he said. “But I think it’s clear that the success of sanctions in achieving their goals is far lower.”

For now, Maduro retains power, and Trump has continued to threaten that he could order a U.S. military intervention “if that’s what’s required.” But regardless of what happens in the short-term, Weisbrot anticipates that the decades-long campaigns against independent leftists governments will only intensify in the coming years, particularly if “neocons” like Bolton and Pompeo continue to drive policy.

“They want the world,” he said. “They want the whole hemisphere to be theirs.”

More on the Subject

Eva Golinger is an American attorney and journalist who was a legal advisor to former Venezuelan president Hugo Chavez. She’s also the author of the best-selling book, “Confidante of ‘Tyrants:’ The Story of the American Woman Trusted by the U.S.’s Biggest Enemies,” which documents her political work in Venezuela and her rise into the close circle of the country’s late president.

“I had breakfast with Hugo Chavez, lunch with Bashar al Assad, cocktails with Putin and dinner with Gaddafi. Fidel Castro sent me flowers, perfume and cigars. Ahmadinejad told me he loved me. Chavez proclaimed me his defender,” she writes.

Golinger sat down with The Globe Post to discuss the unraveling political crisis in Venezuela and the Trump administration’s efforts to overthrow the government of Nicolas Maduro.