When a Zika virus outbreak in Brazil was reported in 2015, the whole world was quick to pay attention. Media coverage increased as more and more countries recorded cases and more and more complications were linked to the disease. Within months of the outbreak, the WHO proclaimed it a “Public Health Emergency of International Concern.” And despite its initial reluctance, the U.S. Congress approved $1.1 billion in Zika funding in September 2016 in response to the public clamor.

When a dengue vaccine scandal erupted in the Philippines in December 2016, the government’s response was also relatively swift. Within days of vaccine manufacturer Sanofi announcing greater than the previously-announced risk of harm, the government suspended the multi-million dollar program. Following allegations – ultimately unproven – that the vaccine caused deaths, the Philippine Senate had earmarked a P1.1 billion ($21 million) special fund for the 800,000 children who received the vaccine in case they would get sick.

As the above cases demonstrate, public outcry and media attention can be a powerful driver of public health action. Governments are often slow with responding to medical issues, and popular pressure can nudge them to act swiftly and decisively. Sometimes this leads to misguided populist reactions, but it can also lead to productive, technocratic responses.

But what about public health emergencies have been around for so long?

Tuberculosis: World’s Leading Infectious Killer

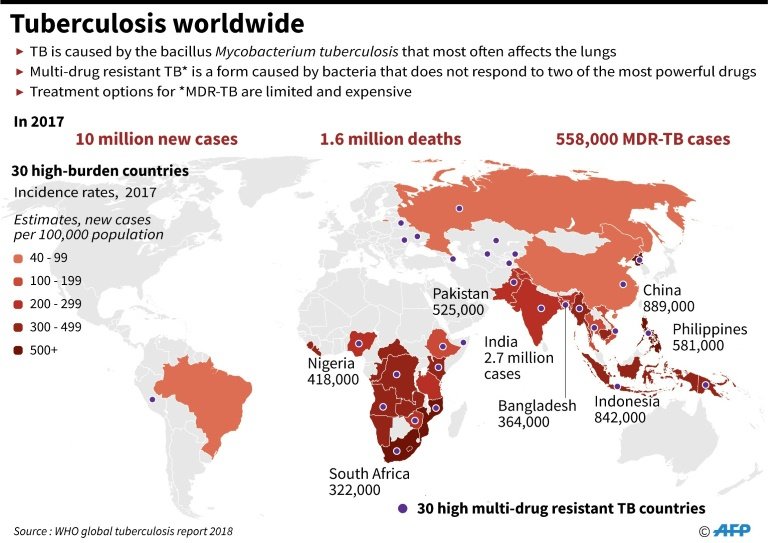

Consider the case of tuberculosis (TB), which for several years now has been the world’s leading infectious cause of death, and one of top 10 global causes of death overall. In 2017 alone, a staggering 1.6 million people died because of the disease. To put things in perspective, during that same period, 110,000 died of measles, while it is estimated that dengue fever causes 22,000 annual deaths. In many countries, tuberculosis has not received attention equal to the gravity of its medical and social consequences.

For instance, in South Africa, where the infectious disease claims the lives of 110,000 people every year, the minister of health said that “people don’t take tuberculosis seriously, they are not scared of it, they don’t talk much about it, even at the leadership level.” In the Philippines, where 26,000 die of the disease yearly, the response has also been muted, despite the public health leadership’s acknowledgment that the country cannot do “business as usual.”

What can explain this disparity in response?

Why Doesn’t Tuberculosis Receive Attention?

First, tuberculosis has been around for so long, making it uninteresting for the public and even for the media, which is (understandably) biased towards the “new” and the “interesting.” This state of affairs has prompted a 2009 editorial of the medical journal The Lancet to call tuberculosis “unsexy” – and unfortunately, this description remains as true today as it was ten years ago.

Second, the fact that tuberculosis is mostly confined to developing countries means that it is unlikely to capture the sustained attention of global media and Western audiences. Although this distribution is rapidly changing (in part due to HIV and rising inequality), the fact that tuberculosis in developed countries would most likely affect the poor and the marginalized means that it would still not be a concern to the global middle class. Unlike measles, which parents might fear their child could get from an unvaccinated classmate. Or unlike Zika, which people feared they could get by simply attending the Olympics in Rio.

Finally, the disease itself lacks the dramatic features of dengue (such as internal bleeding) or Zika (such as microcephaly); or the moralized undertones of HIV; or the untreatable, highly-contagious nature of Ebola. Tuberculosis is very treatable, it’s just that the treatment takes so long – at least six months – and consequently, many people drop out of it.

Controlling Tuberculosis

To the credit of many governments and international organizations, tuberculosis has received some significant funding over the past two decades, not least from The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria; Stop TB Partnership; TB Alliance; USAID; and other initiatives.

As the high-level meeting on ending tuberculosis convened by the U.N. General Assembly last year shows, governments are very much aware that aside from the sheer human toll of the disease, the growing threat of multi- and extensively-drug resistant tuberculosis plus its particularly-devastating impact on HIV patients raises the stakes in controlling the disease.

#TB is spread through the air from one person to another. Learn more about #tuberculosis and find out if you should be tested: https://t.co/zmYqlpfl5L pic.twitter.com/krOC1sTksR

— CDC TB (@CDC_TB) June 14, 2019

Still, stronger action is required particularly from national and local governments. As Harvard Professor Mary T. Bassett has pointed out, there is a need to “work within structures” – so much can be accomplished with a supportive government. Even if there is no public clamor for a strong response – and without diminishing the importance of the other diseases mentioned in this piece – heads of state and ministers of health need to take political and technical leadership and devote government’s resources to stopping tuberculosis.

This work entails re-evaluating old strategies, considering new ones (such as new drugs and diagnostic modalities), and addressing the social determinants of the disease (such as access to housing and nutrition). But as the case of India shows, it also involves well-established, but often-neglected steps like ensuring the availability of existing treatments, making clinic hours friendly to patients, giving the patients the proper advice about side effects and the importance of medication adherence, and guaranteeing that tuberculosis funds are not wasted to corruption.

Failure to act urgently and vigorously will mean thousands killed every day – and a near-incurable disease that can plague future generations. Necessity, not publicity, must drive the response to one of the greatest public health emergencies of our time.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of The Globe Post.