It didn’t take long for President Donald J. Trump to act on one of the more ominous refrains of his candidacy.

While on the campaign trail, he called for a “total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States.” Just one week after taking the oath of office, he signed an order bringing refugee admissions to a screeching halt, drastically cutting the number of refugees that would be allowed into the United States, and singling out citizens from several Muslim-majority countries as being barred from entry. The inhumanity of this first ban was shocking then. It still is now.

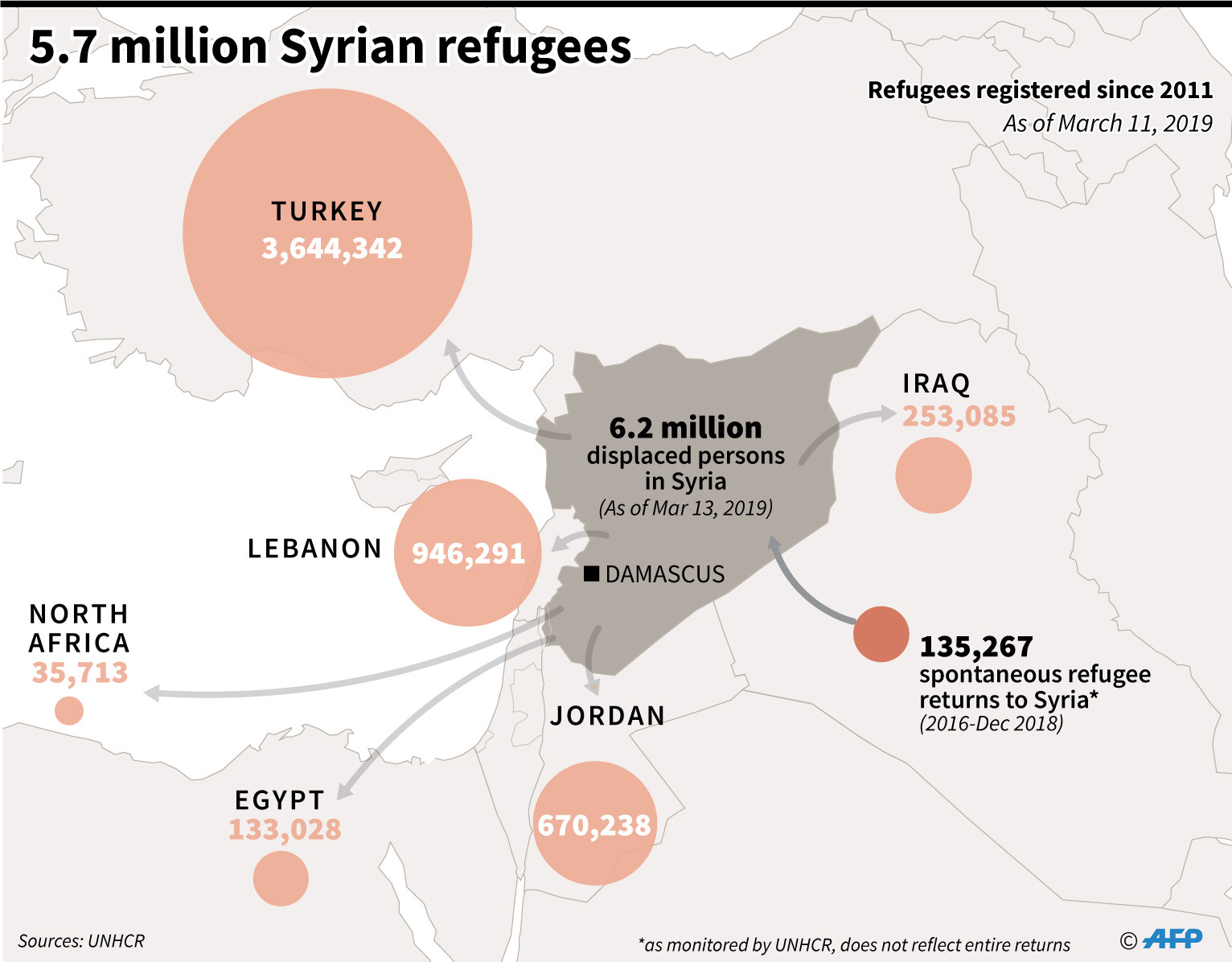

While the first ban would morph over time in the wake of court decisions and massive public outcry, what we’ve been left with today is equally as impactful on refugees. The refugee admissions goal was cut and then cut again, to historic lows. Extreme vetting has been implemented, with particularly egregious focus on refugees from targeted countries. Syrian refugees, who initially were barred indefinitely, have only been admitted at the rate of a few hundred this year, despite their acute need for resettlement.

This deliberate choice of discriminatory and restrictive policies has left the U.S. refugee program a shadow of itself, and left tens of thousands of refugees in an agonizing holding pattern, including families who were once just a few days away from a plane ride to a new life in the United States.

Refugees in Lebanon and Jordan

Recently, I traveled with my colleagues to Lebanon and Jordan, where many refugees from Syria, Iraq, and other conflict-affected countries have fled while enduring the years-long process of applying for refugee status and resettlement. Facilities and services for refugees in these countries are stretched far too thin, as fewer families are resettled and much needed humanitarian assistance is stretched thin. Those that have managed to eke out a temporary life outside of the camps find their resident status nearing expiration with the possibility of extension uncertain. While the world has largely moved on, they are running out of options and time.

In late December 2016, Amina and Ahmed were told they were accepted for resettlement to the United States and should prepare to move with their four young children. They even knew the city that they would make their new home: Richmond, Virginia. It was the news they had been waiting for, three years since they fled their home in Aleppo, Syria to seek temporary refuge in Beirut. They gave away many of their belongings in preparation for leaving for their new home.

But when that fateful ban was signed mere weeks later, their dreams were shattered and indefinitely put on hold. They were told to wait until the ban was over. They are still waiting.

Meanwhile, Ahmed will soon lose his residency status, exposing him and his family to the risk of arbitrary arrest, detention, and forcible return to Syria, where in addition to the ongoing conflict, Ahmed faces the prospect of involuntary conscription into the Syrian army. The carpet store where he works is closing in a few months, and he will be forced to look for a job without a residency permit. The family used to receive support from the U.N. refugee agency, but that was discontinued due to budgetary shortfalls. “Every time the phone rings, we think it will be positive news,” he told our team. “It is our only hope.”

Elsewhere, in Jordan, the Azraq refugee camp in Jordan is home to approximately 40,000 people but it looks and feels like a military compound. Rows and rows of identical, anonymous shelters are set up in a grid system. From the air, the camp looks like an isolated checkerboard on the desert plain. On the approach to Azraq, a city of tents appears on the horizon, an anonymous city of plain white structures emerging out of nowhere.

The residents of the camp are trapped there, largely unable to leave unless they choose to return to their home countries to face the dangers that caused them to flee in the first place. Leaving the camp without permission can result in deportation.

So they remain there, surrounded by walls topped with concertina wire. Some of them, like a woman we met named Fatima, were able to get jobs with some of the international non-governmental organizations that operate there. But Fatima, an English teacher in her previous life in Syria before a plane destroyed her family’s home, recently lost her job because the organization she worked with lost its funding, an echo effect of the sudden drop in support from the United States. Now the food vouchers she receives are barely enough for her and her husband to support themselves and their son.

“The mountain is in front of us, and the sea is behind us,” she told us. She doesn’t understand why the United States stopped helping. “We have qualified professionals, qualified educators, skilled people who are self-sufficient.” She cannot go back home. Everyone who returns, she said, is arrested or killed.

World Refugee Day

This World Refugee Day must serve as a reminder of the cruel repercussions of the Trump administration’s actions, and the power that same administration holds to make things right. The administration should start by restoring the refugee admissions goal to a level that begins to match the need and U.S. capacity. The discriminatory policies of the Trump administration are leaving tens of thousands of people to languish in situations where their lives are put indefinitely on hold.

As the years go by while these draconian policies remain in place or even worsen, a generation of children is being forced to grow up deprived of their basic human rights. The news cycle has moved on. They cannot.

Names in this article have been changed to ensure safety.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of The Globe Post.